March 4

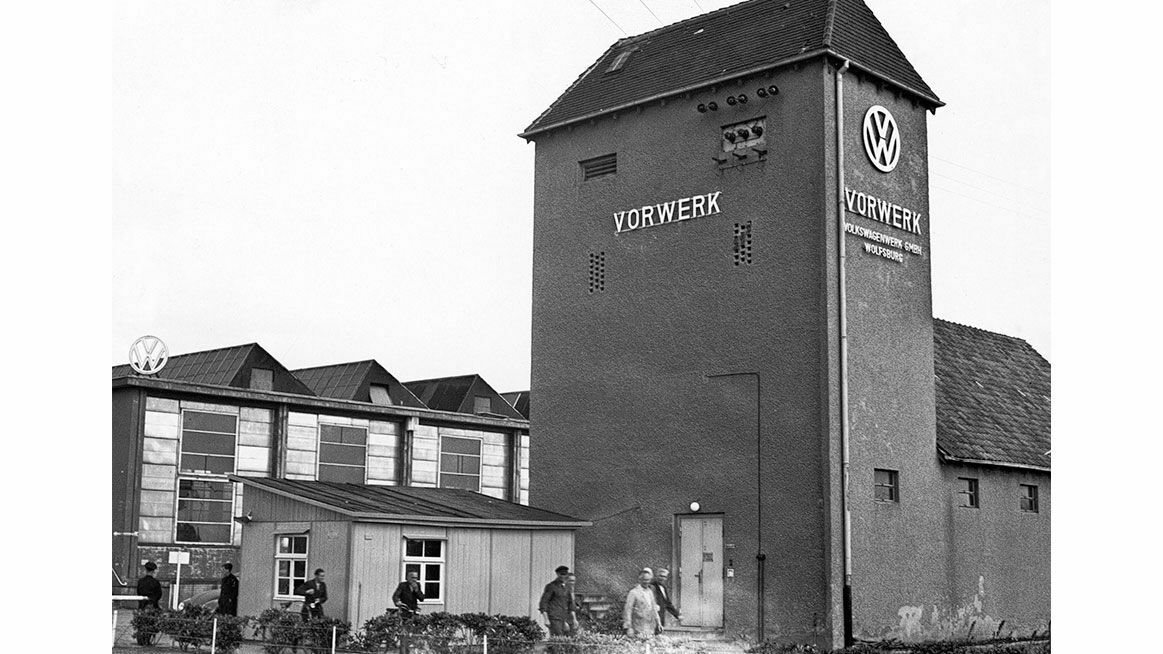

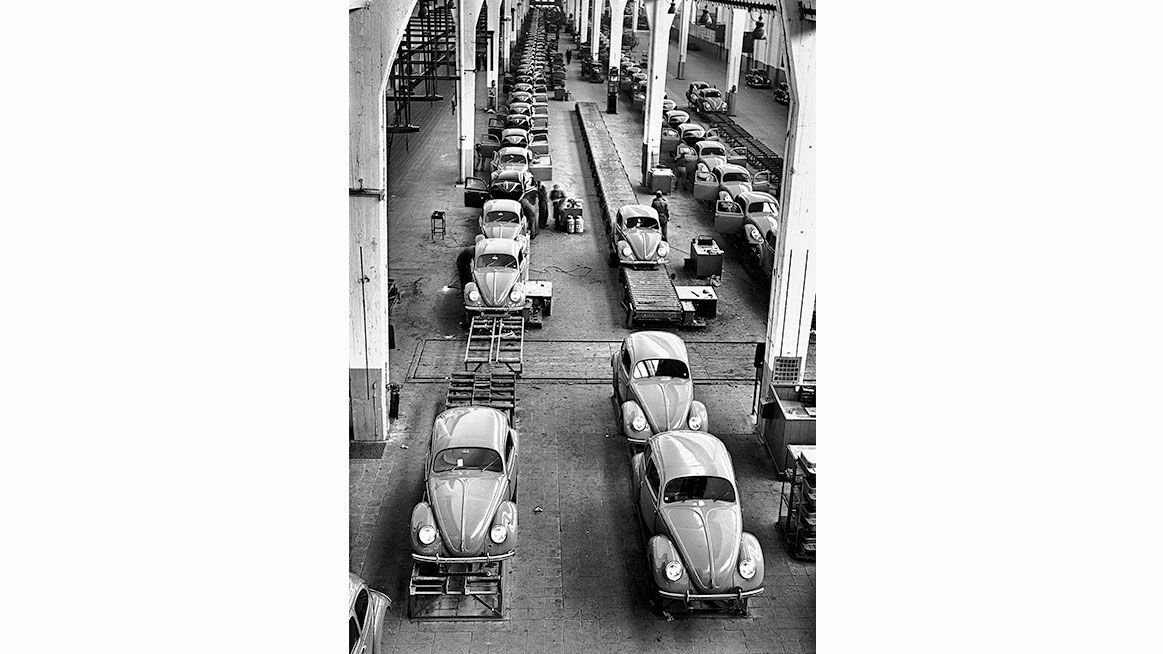

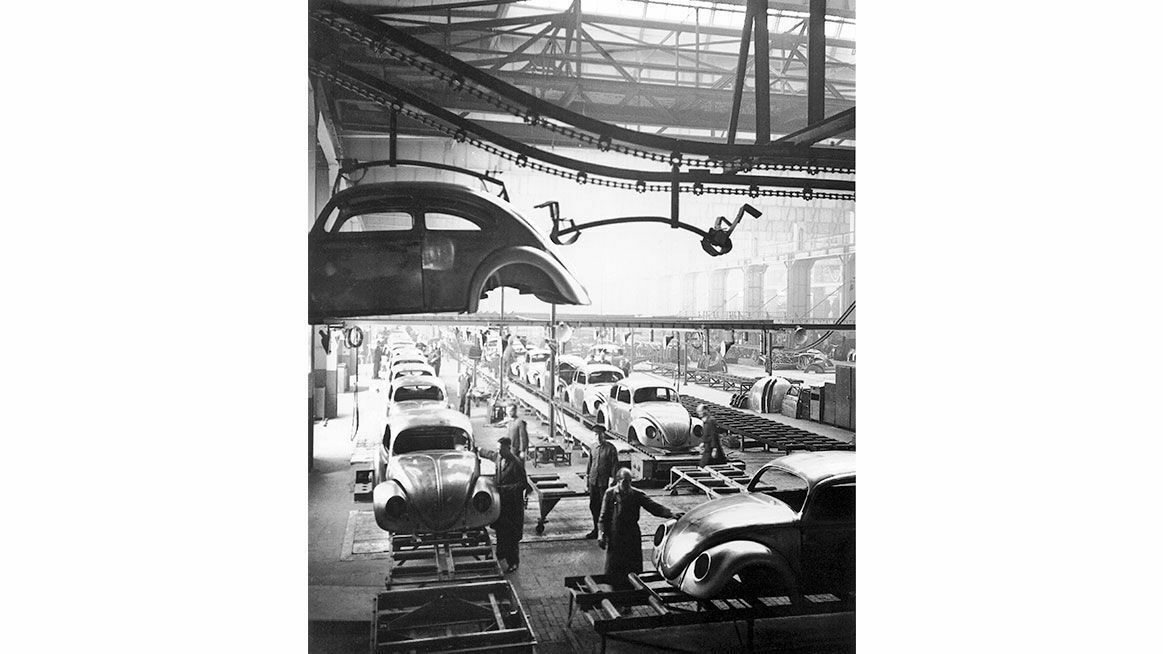

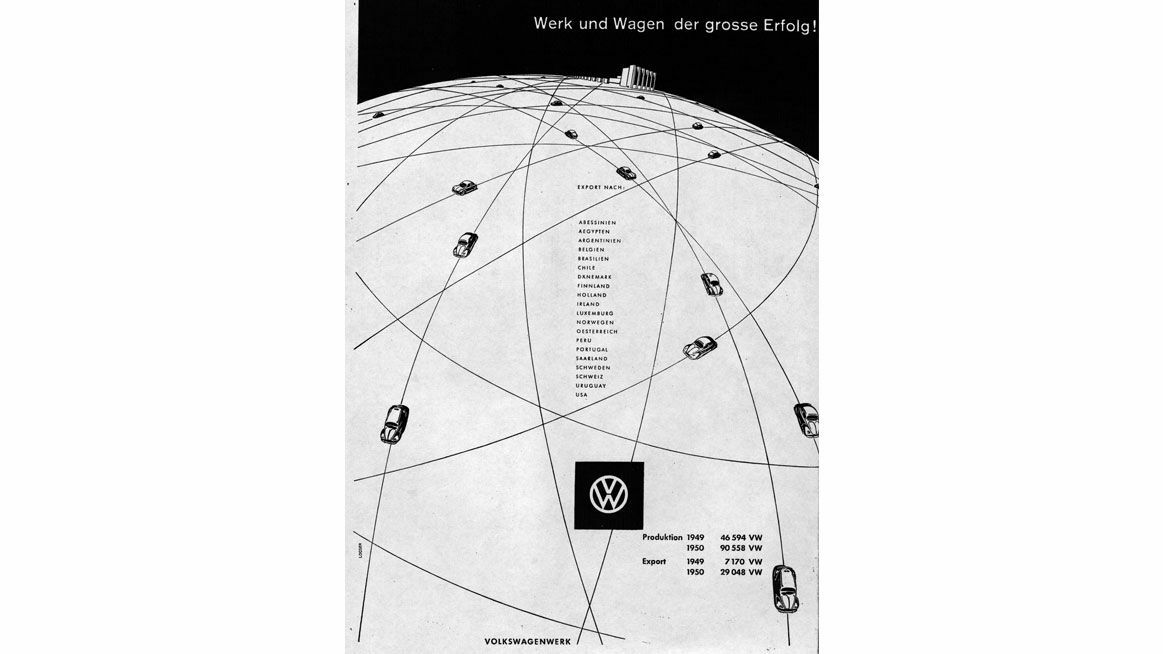

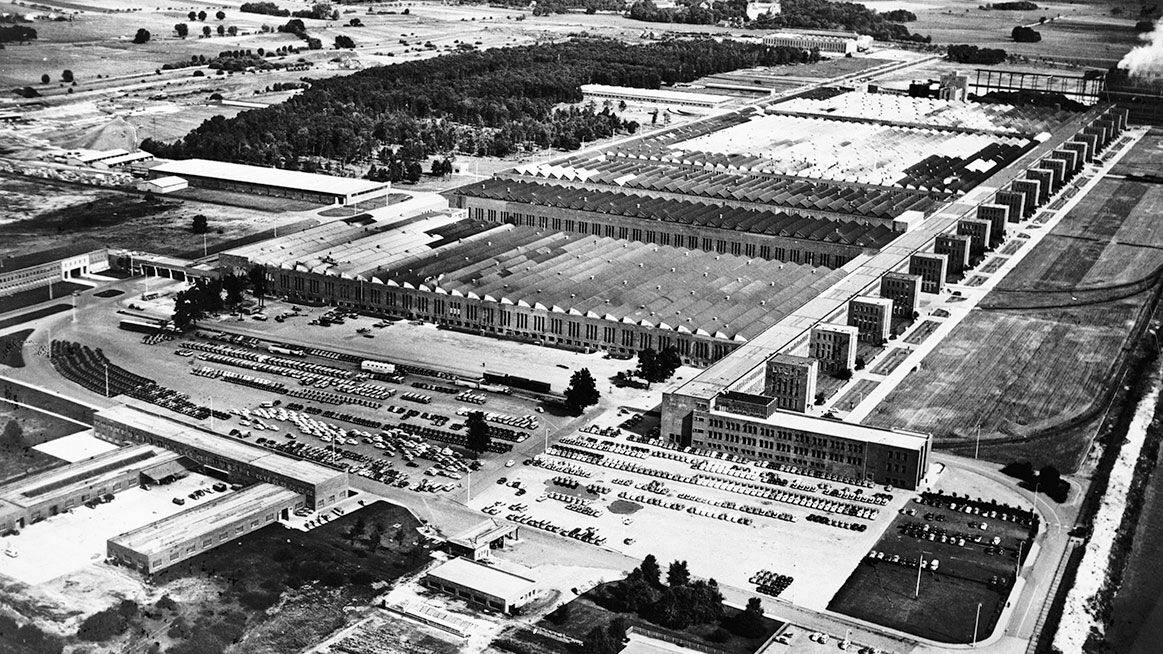

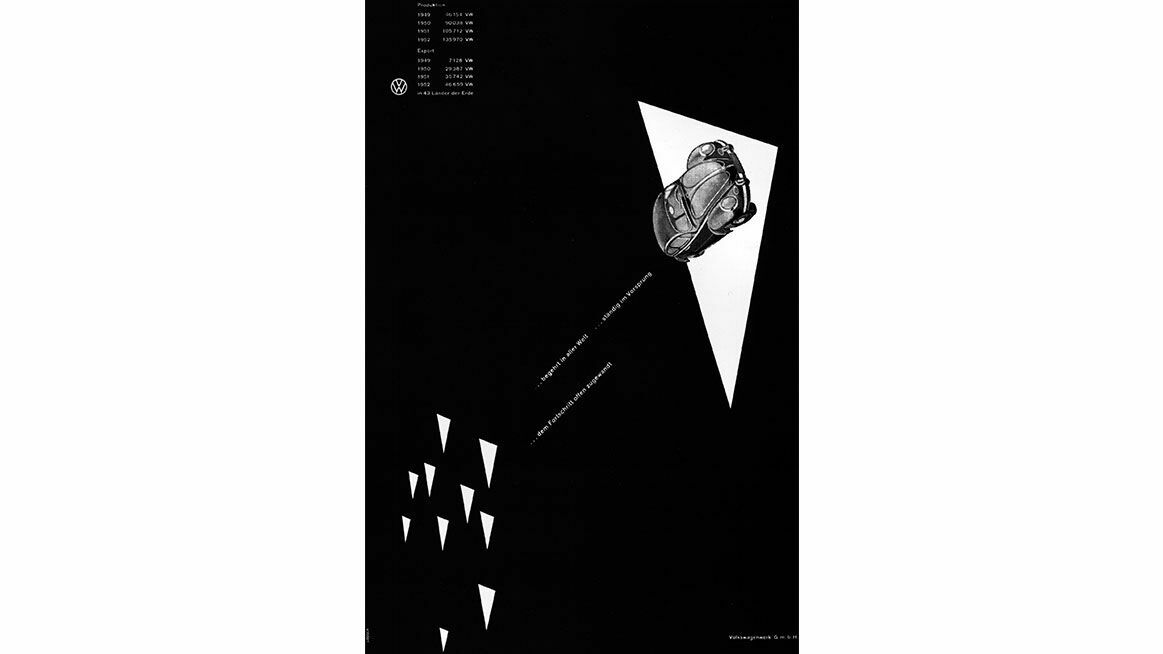

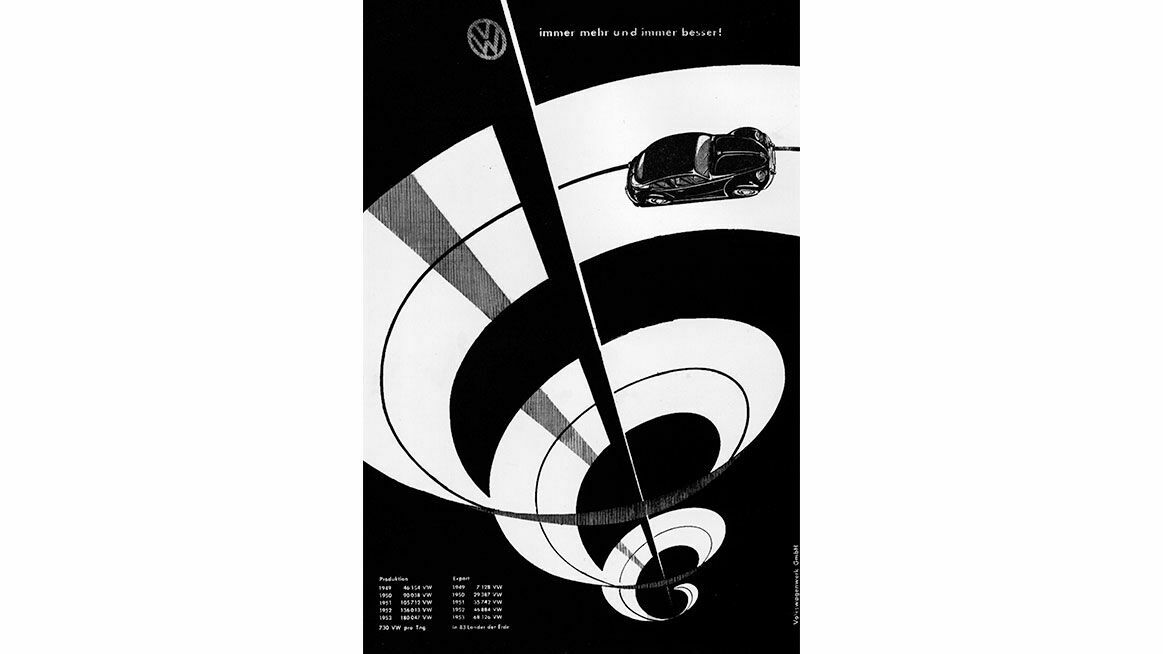

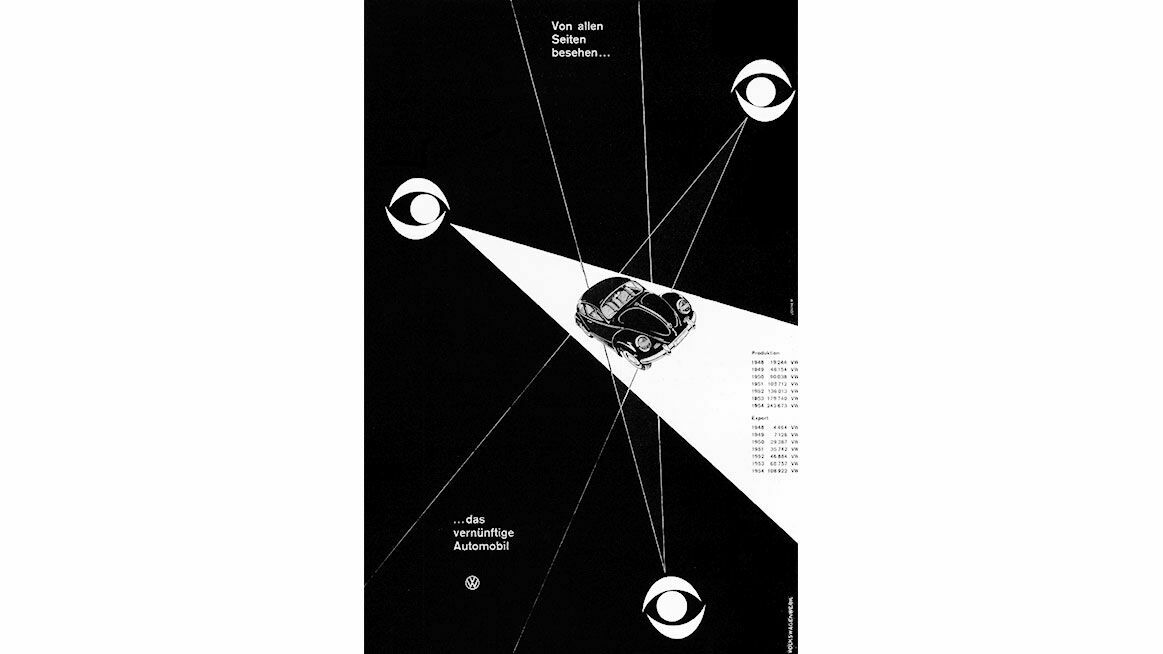

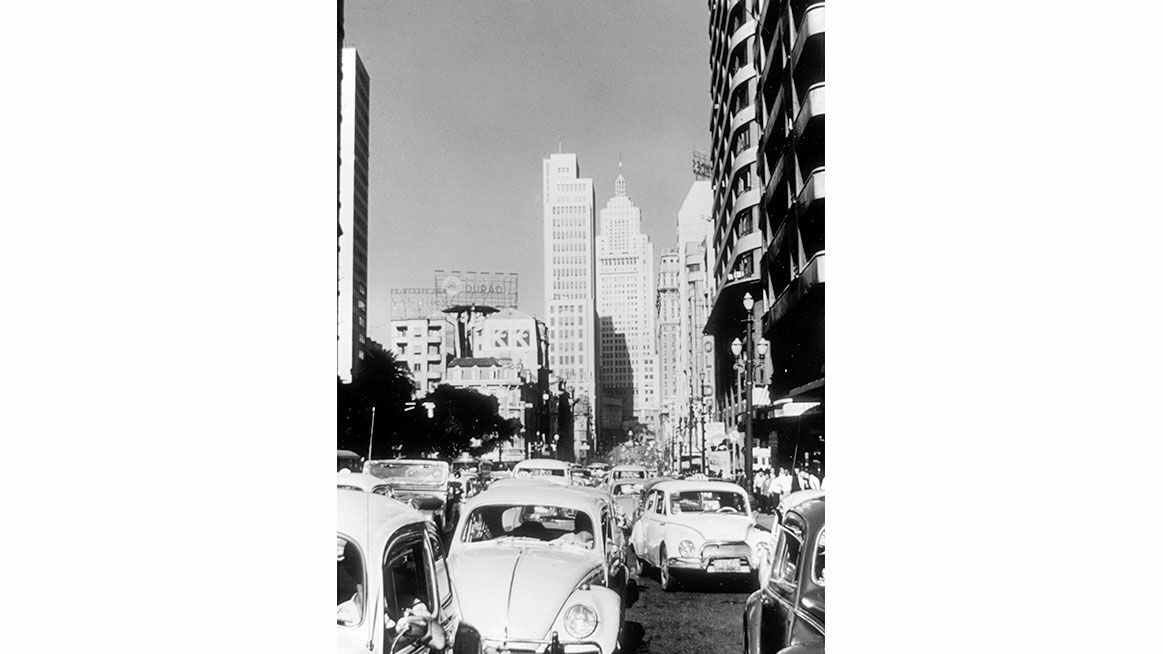

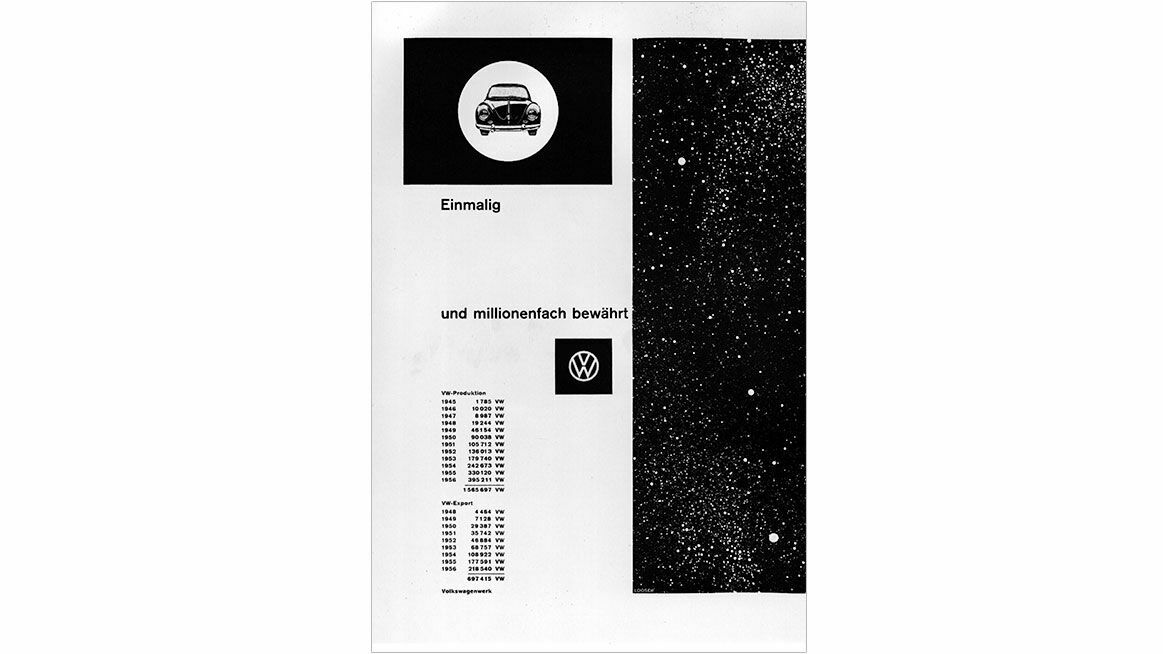

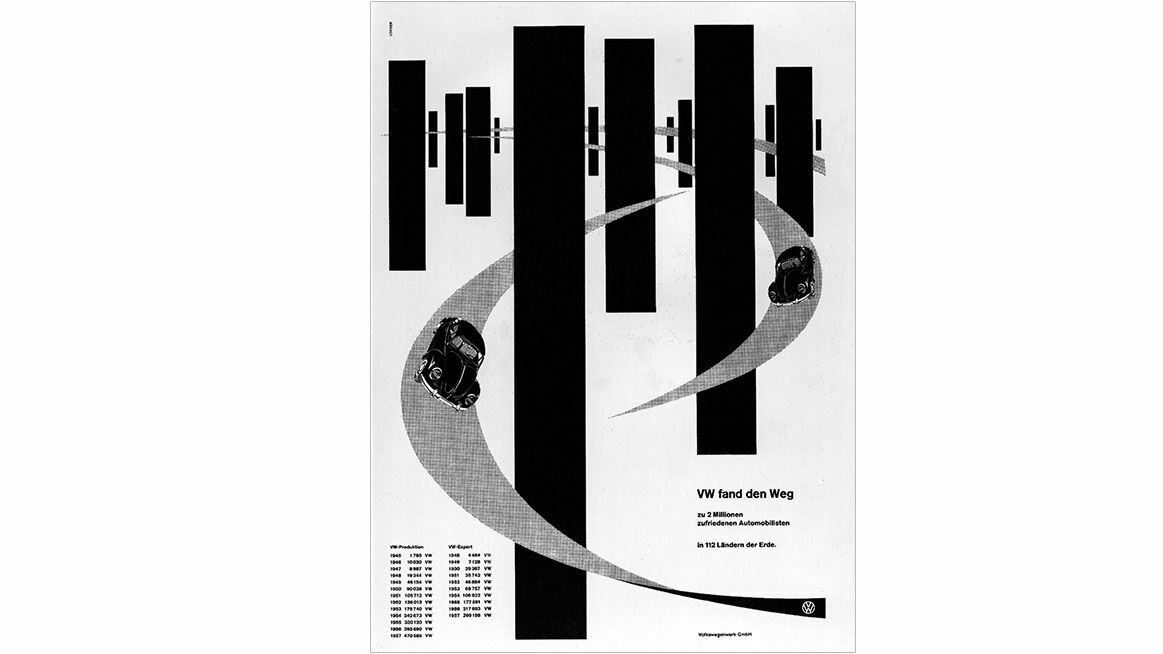

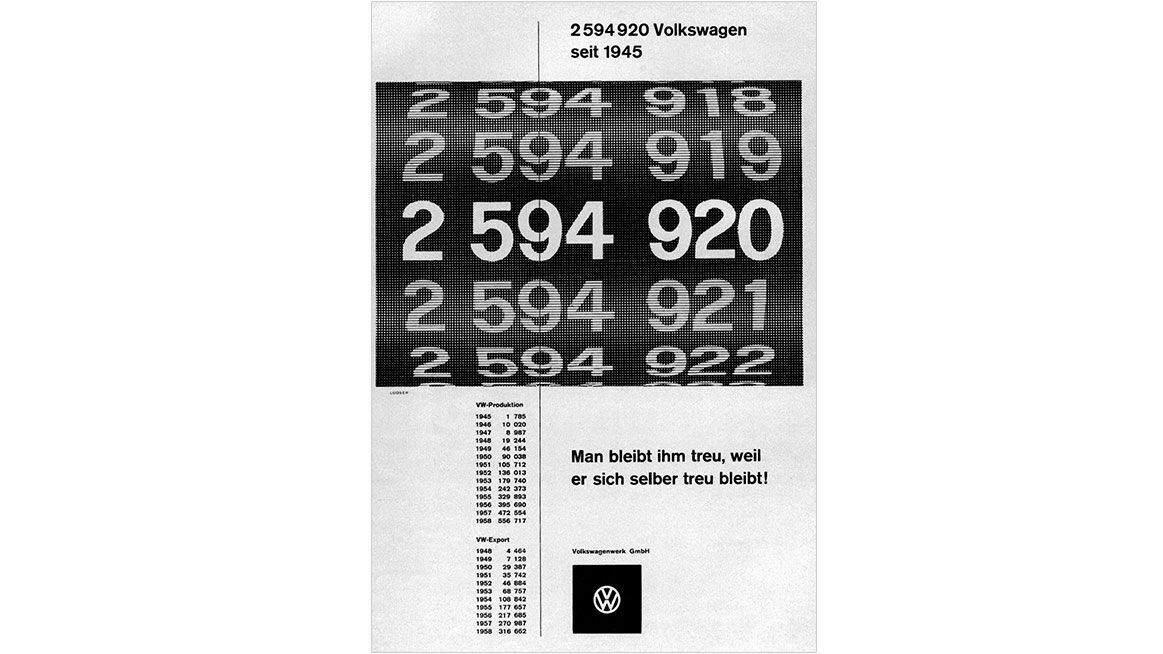

Volkswagen was already considered a symbol of West Germany’s Economic Miracle, or “Wirtschaftswunder”, even by its contemporaries. The company’s success matched that of the Beetle itself. The factory’s capacity as well as the rationalisation initiative introduced in 1954 created the technical preconditions for mass production of the Volkswagen Saloon and the Transporter. Volkswagen was able to shape its long-term growth strategy by combining mass production, global market orientation and the integration of its workforce. In 1950, the Wolfsburg company exported one third of its car production to 18 countries, most of them in Europe. The main export markets were Sweden, Belgium, the Netherlands and Switzerland. By exporting 1,253 vehicles to Brazil for the first time, South America emerged as a second important focus of the company’s activities, especially at a time when the import of US models there almost came to a complete stop because of a shortage of dollar reserves. Volkswagen gave priority at an early stage to supplying this key future market.

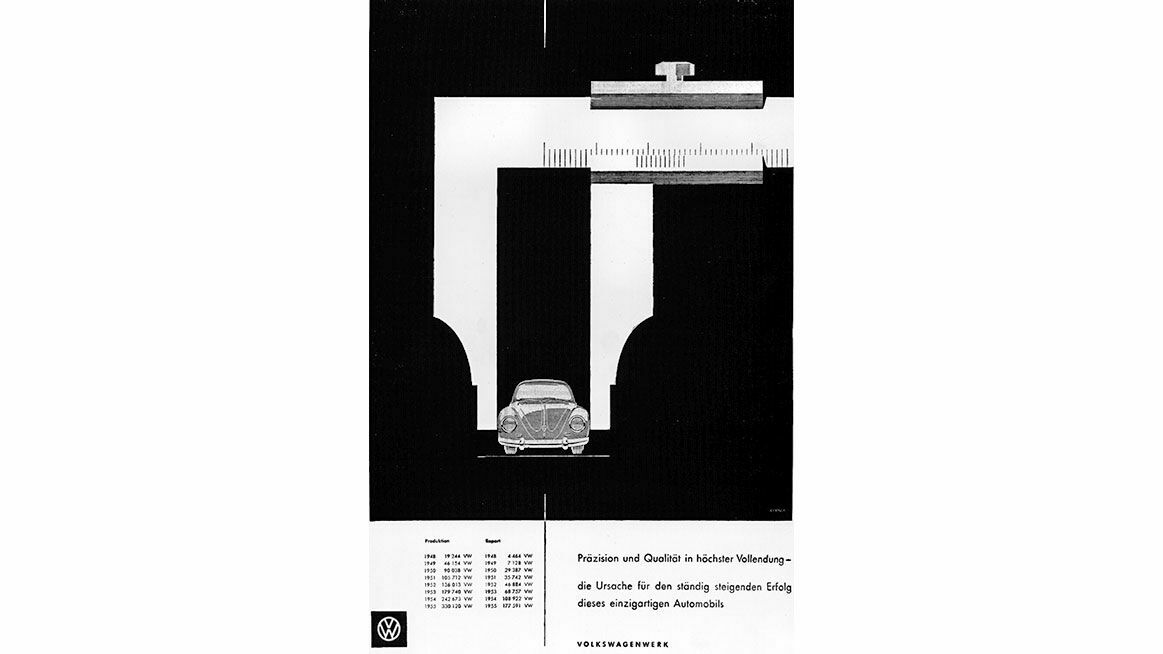

Europe’s economic recovery and the emerging industrialisation of many countries outside Europe created a favourable situation for the export of Volkswagens. International trade based largely on bilateral agreements proved beneficial for Volkswagen. The dollar shortage in most countries temporarily weakened the US competition, while the export prospects of German rivals were limited by their low production capacity. As a public company, Volkswagenwerk GmbH could also hope for the support of the Federal Government, which, by negotiating trade agreements, opened up export possibilities for German industry. With a share of up to 50 percent of all German car exports, Volkswagen was the most important earner of foreign currency and the leading German car exporter during the 1950s.

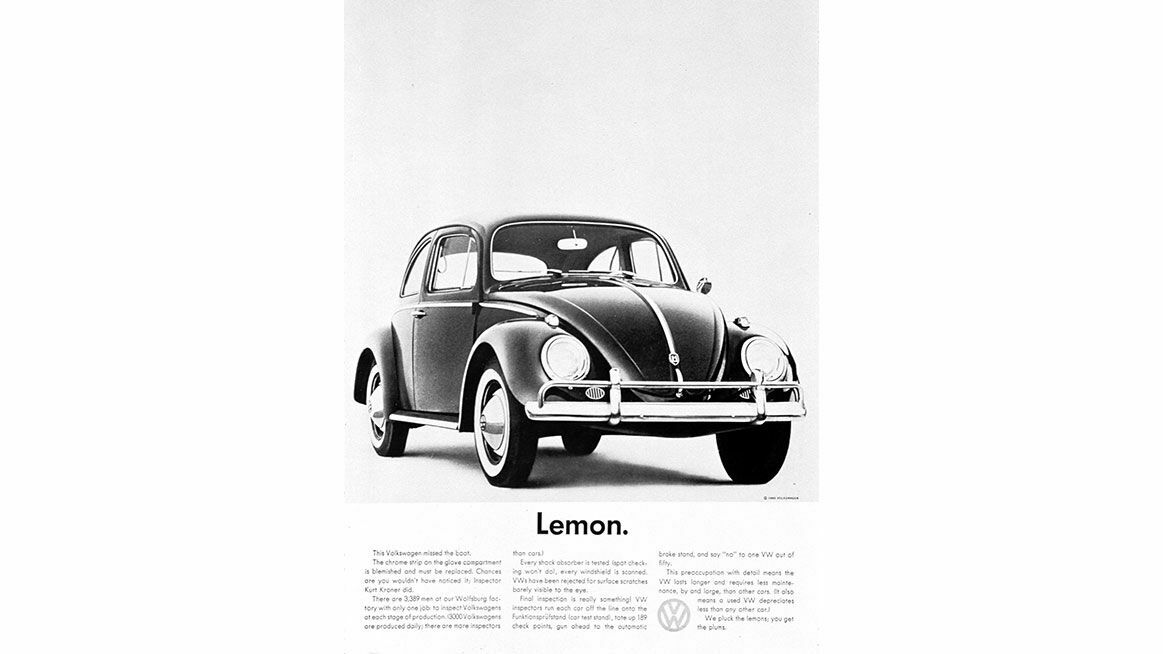

The systematic expansion of the export business during the first half of the 1950s was not entirely free of trouble and risk, however. Investments were at first only rewarded with narrow profit margins, because Volkswagen’s price calculations had to take into consideration the establishment of its products on international markets, and so the company exported its products at close to cost. In addition, the establishment of a production site in Brazil ran into difficulties because of political and economic instability. Problems were also encountered when a sales organisation for the US market was set up. Top American dealers were already tied to exclusive contracts with domestic manufacturers, and the standard 30 percent trade discount made competitive pricing difficult.

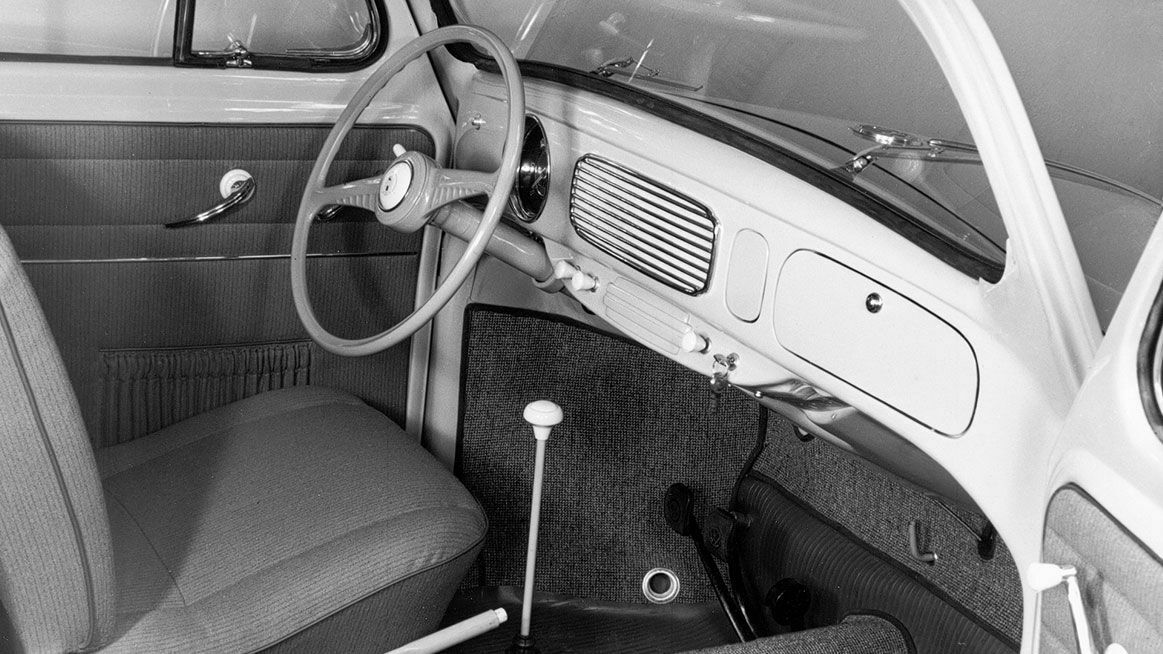

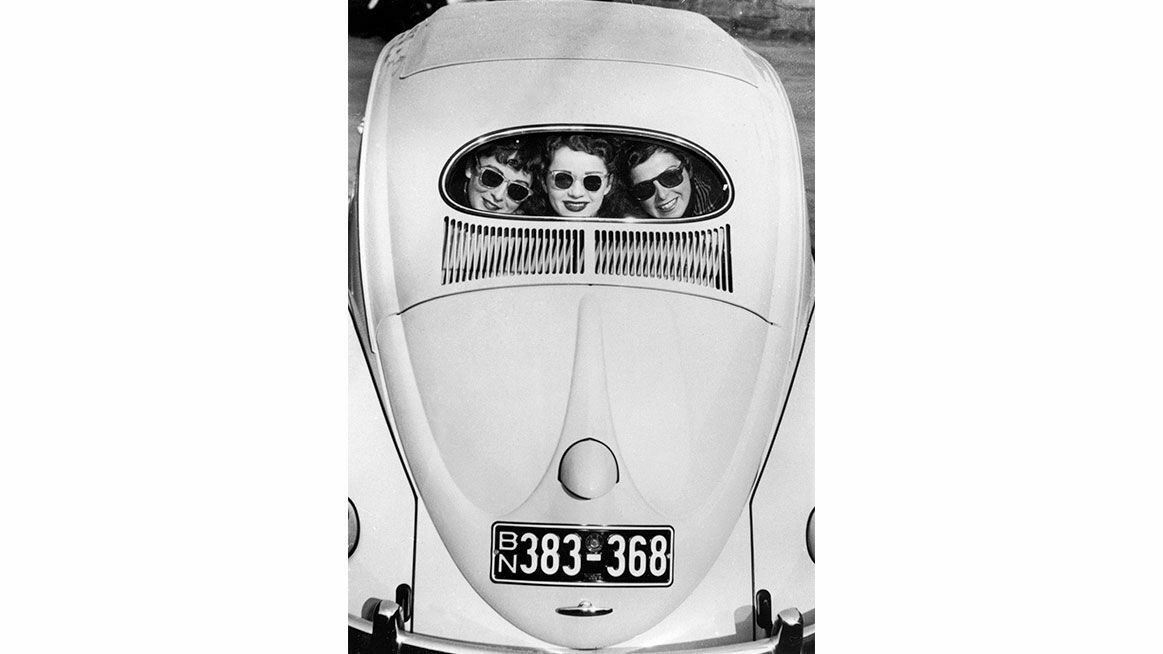

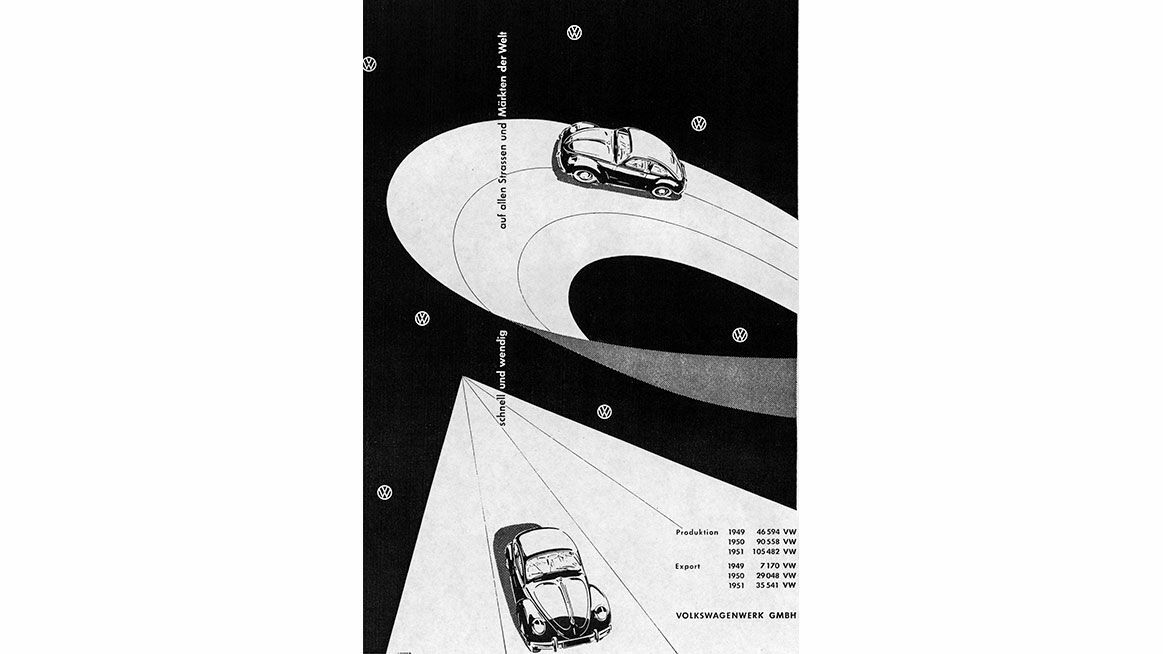

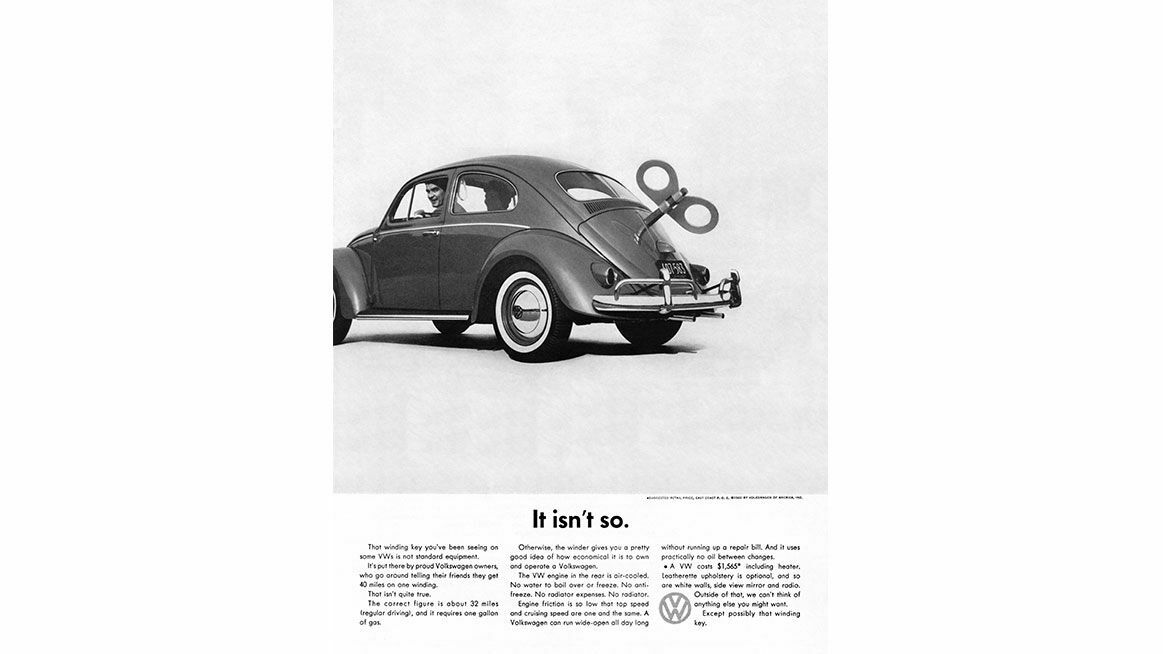

Despite these problems, Volkswagen was able to break into the European, American and African markets by the mid-1950s. This was thanks for the most part to its engineering attributes and the quality standards of the continuously improved saloon. The Beetle enjoyed the reputation of being an economical and reliable car, especially suited to the needs of developing countries because of its fuel efficiency and its robust design suitable for regions with underdeveloped roads. On the other hand, Volkswagenwerk GmbH was diligent when entering new markets, supporting its products with a sales and service network. The company’s management believed that long-term success would only come from an organisation that included a close-knit network of service centres equipped with special tools and well-trained personnel, and capable of supplying the required replacement parts. Volkswagen’s excellent reputation in this regard provided a key competitive edge on international markets. Volkswagen demanded high levels of investment from its dealers in order to guarantee professional customer service. In the strategically important Canadian and US markets, Volkswagenwerk GmbH set up its own sales network. At the same time, production sites were established in Brazil, South Africa and Australia. The Wolfsburg company moved onto the international stage early in its development, laying the foundations for a worldwide production network.

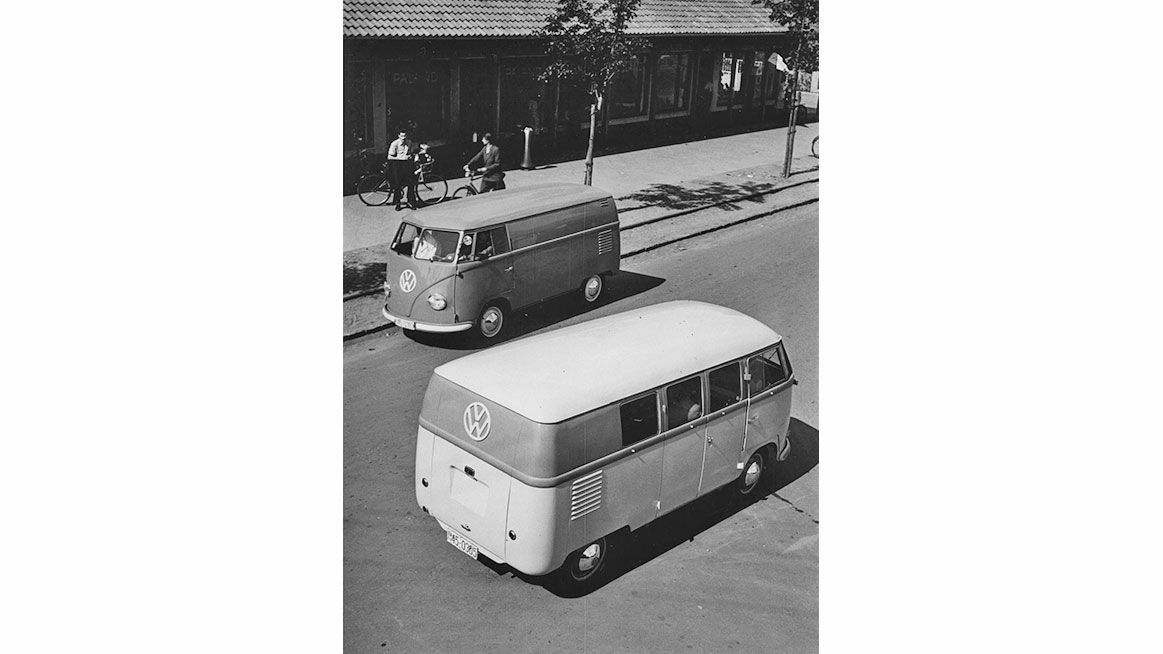

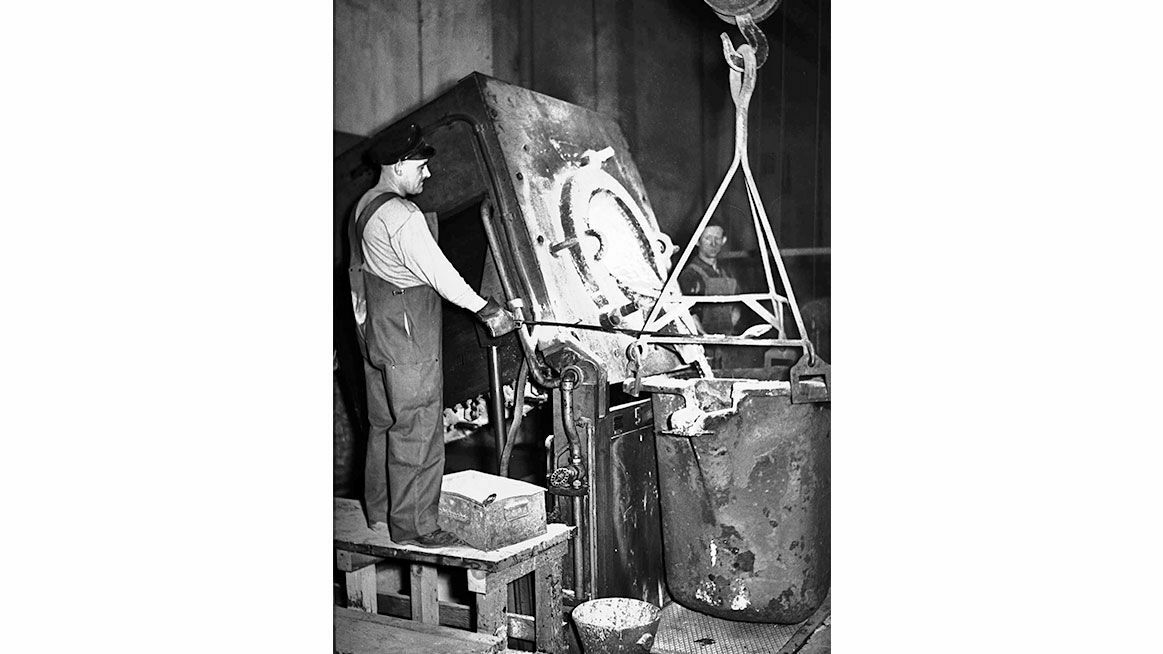

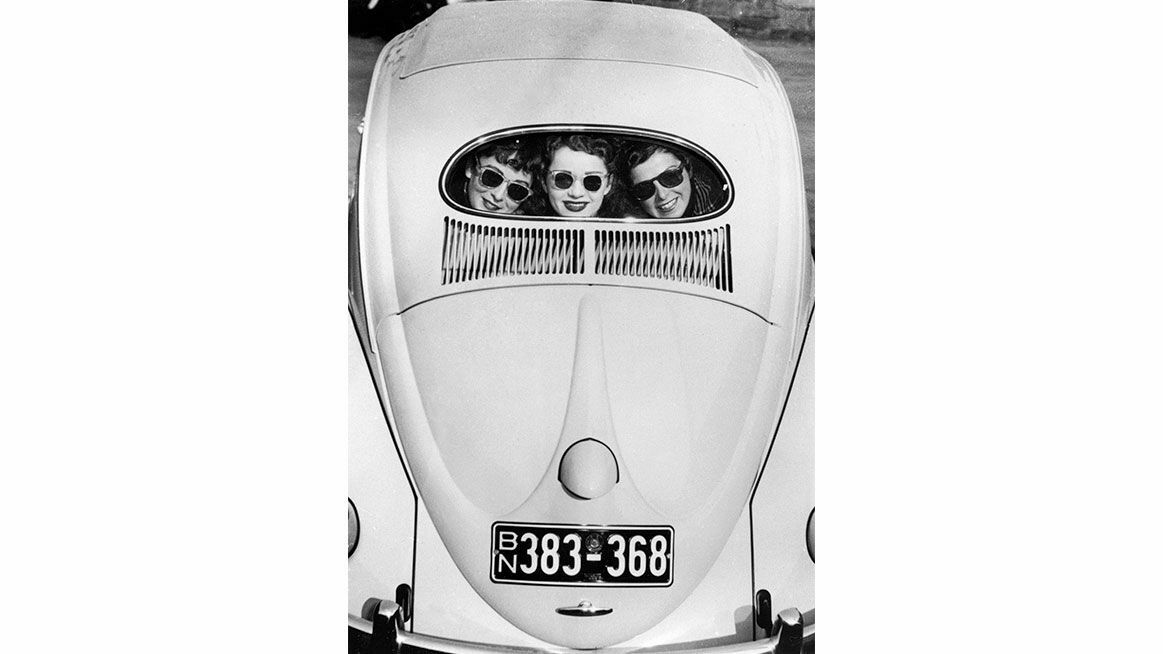

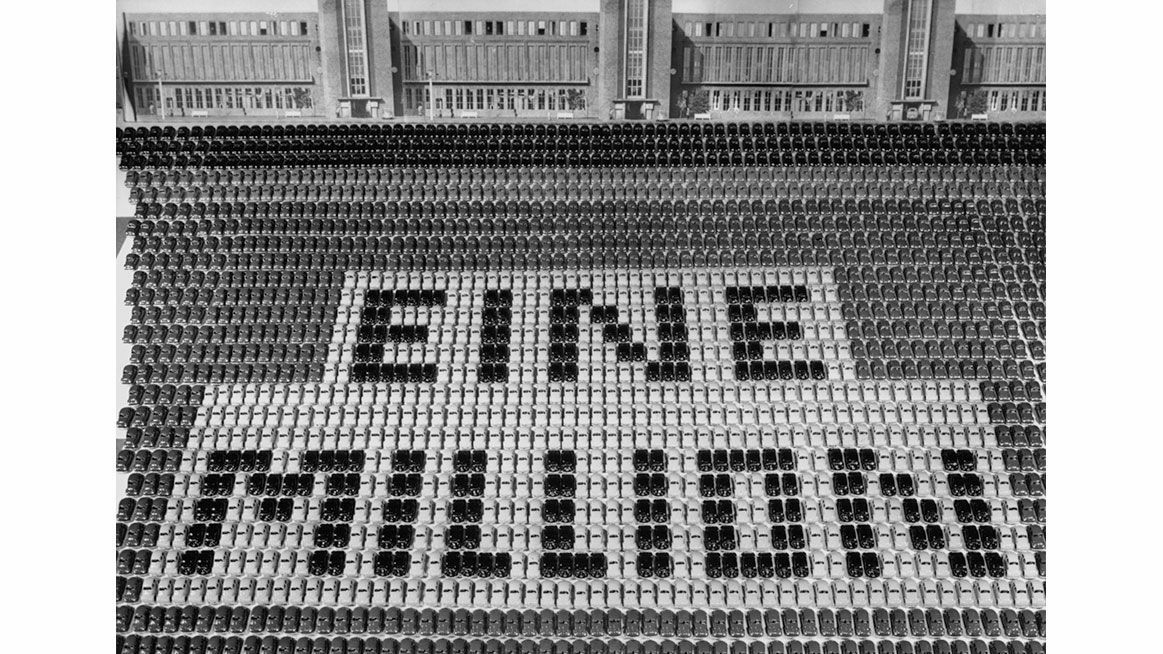

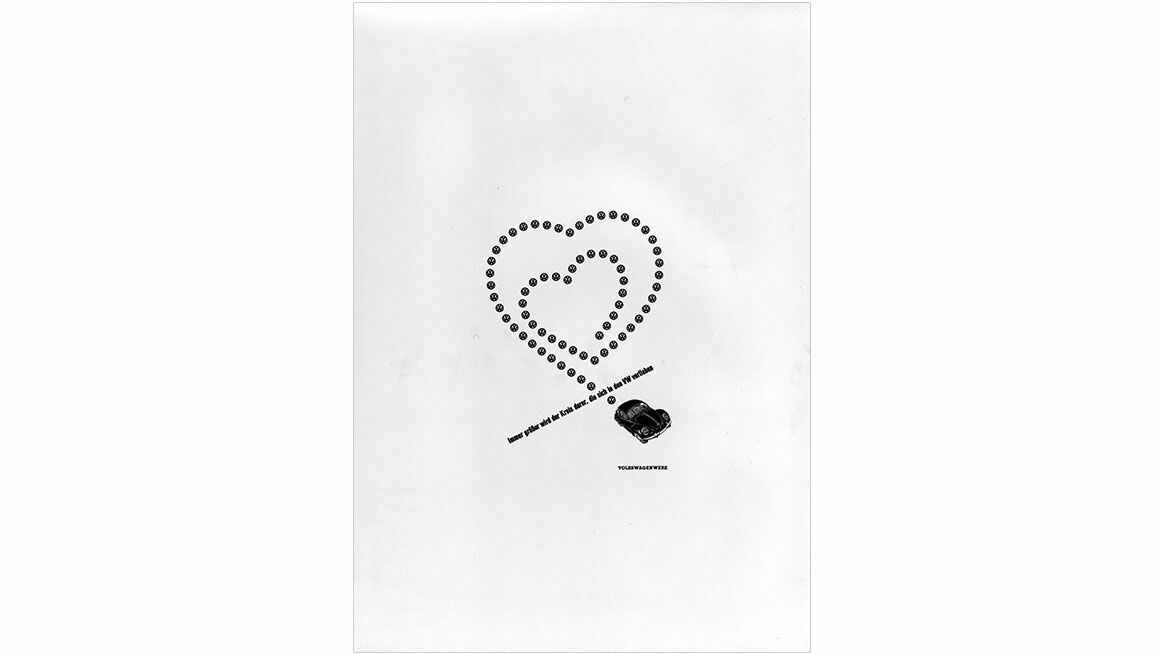

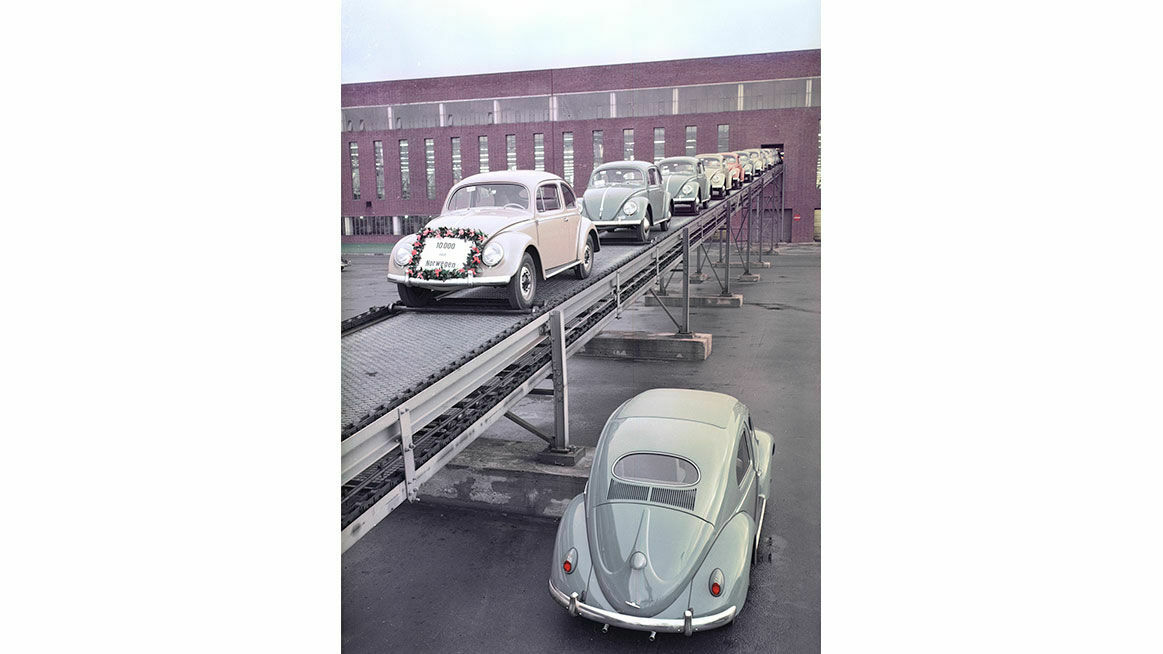

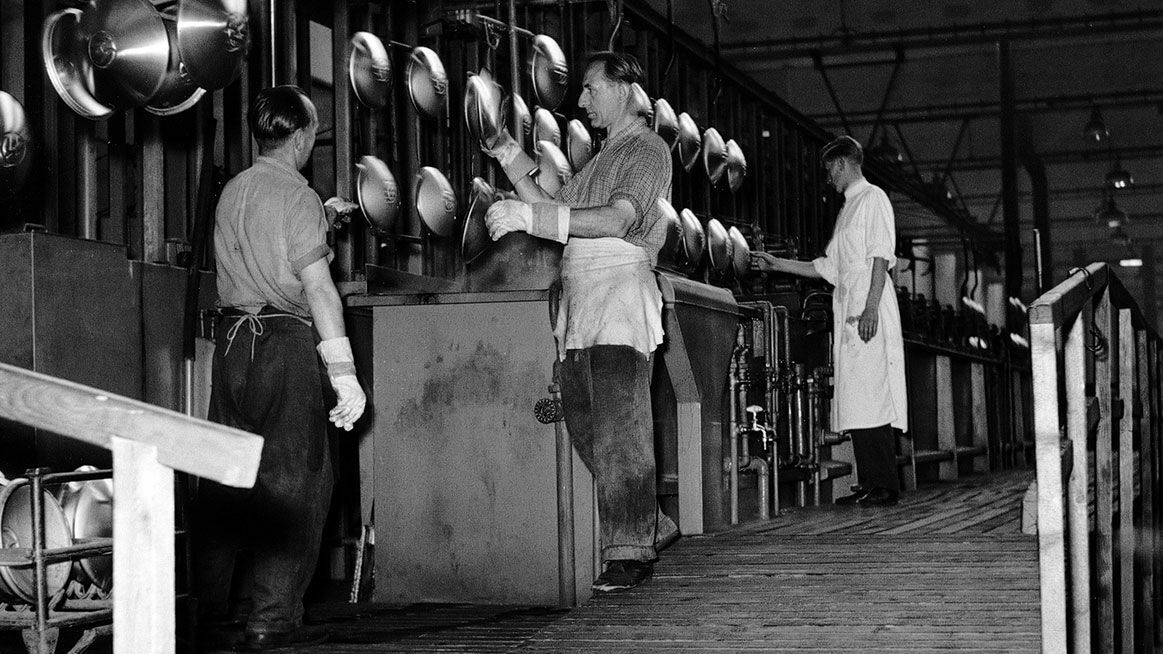

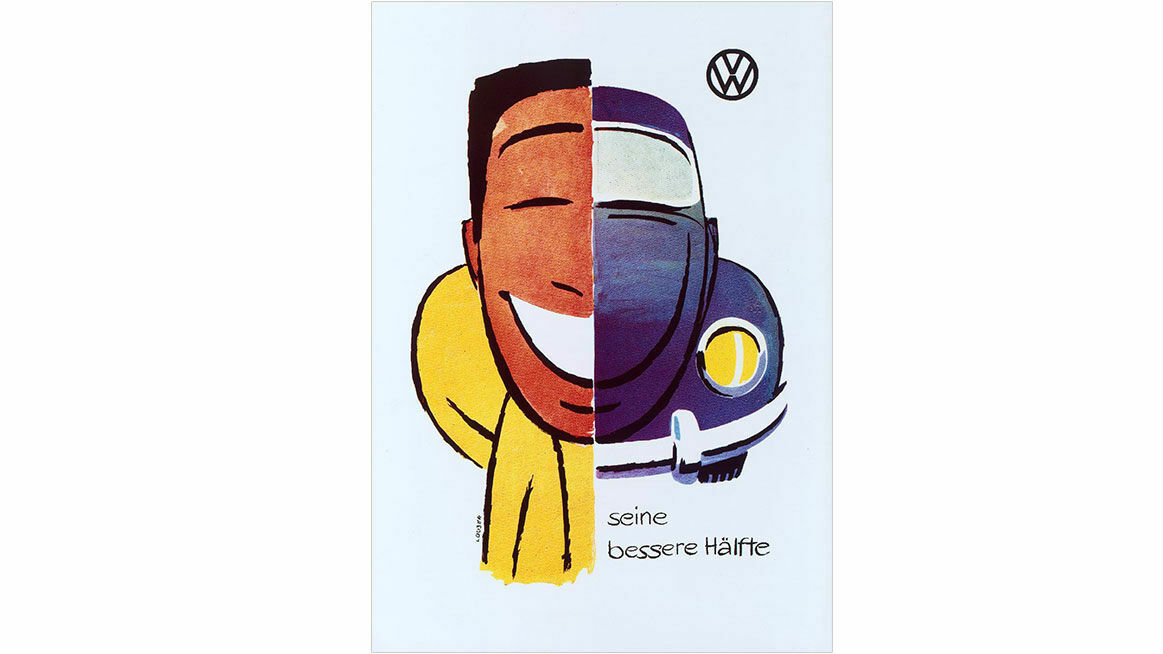

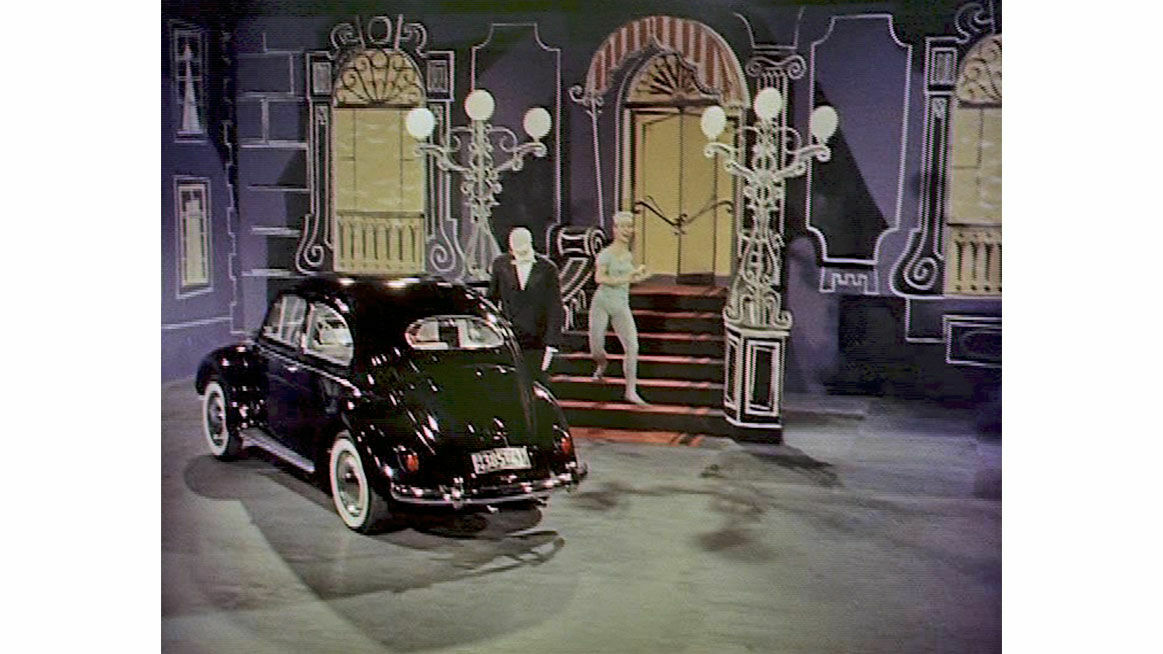

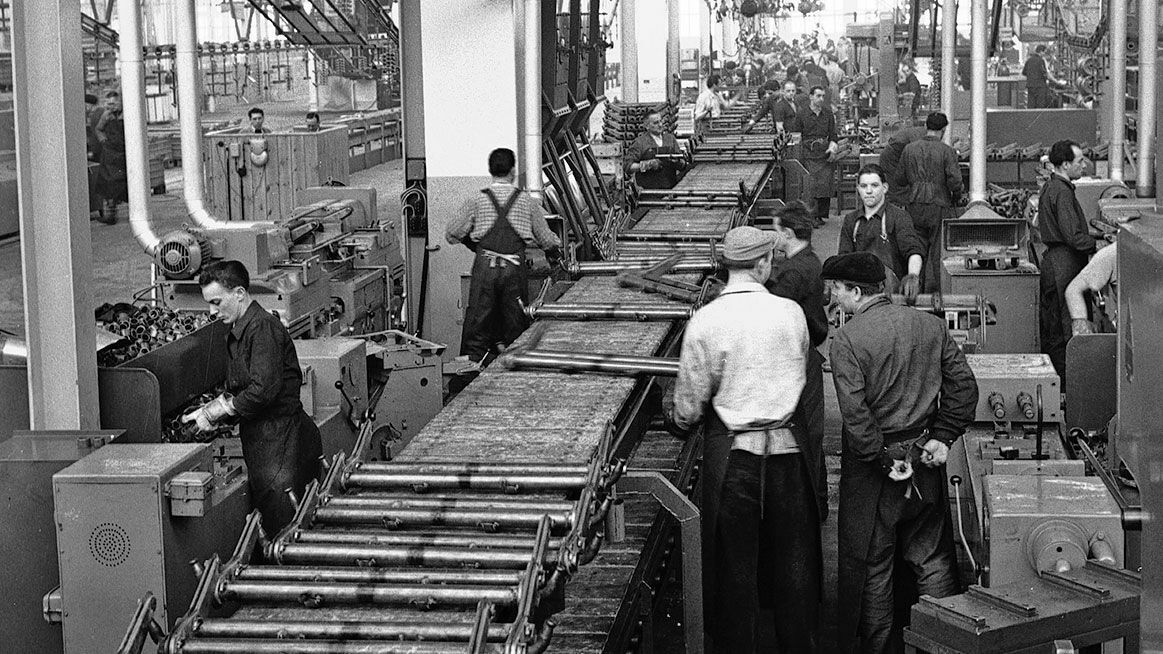

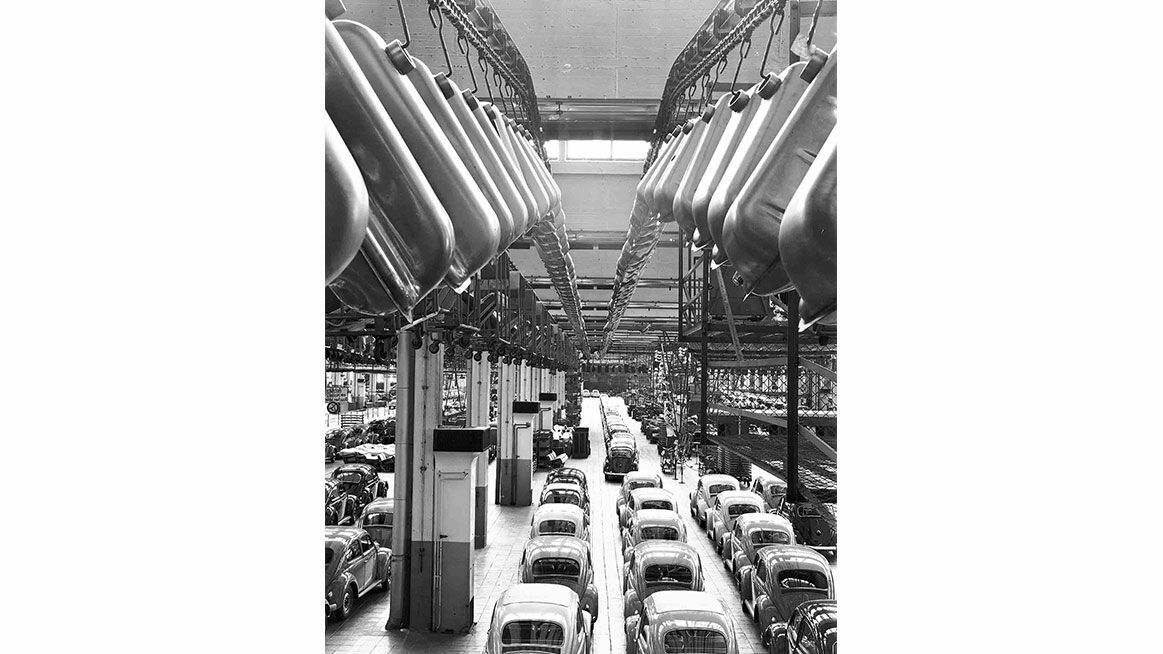

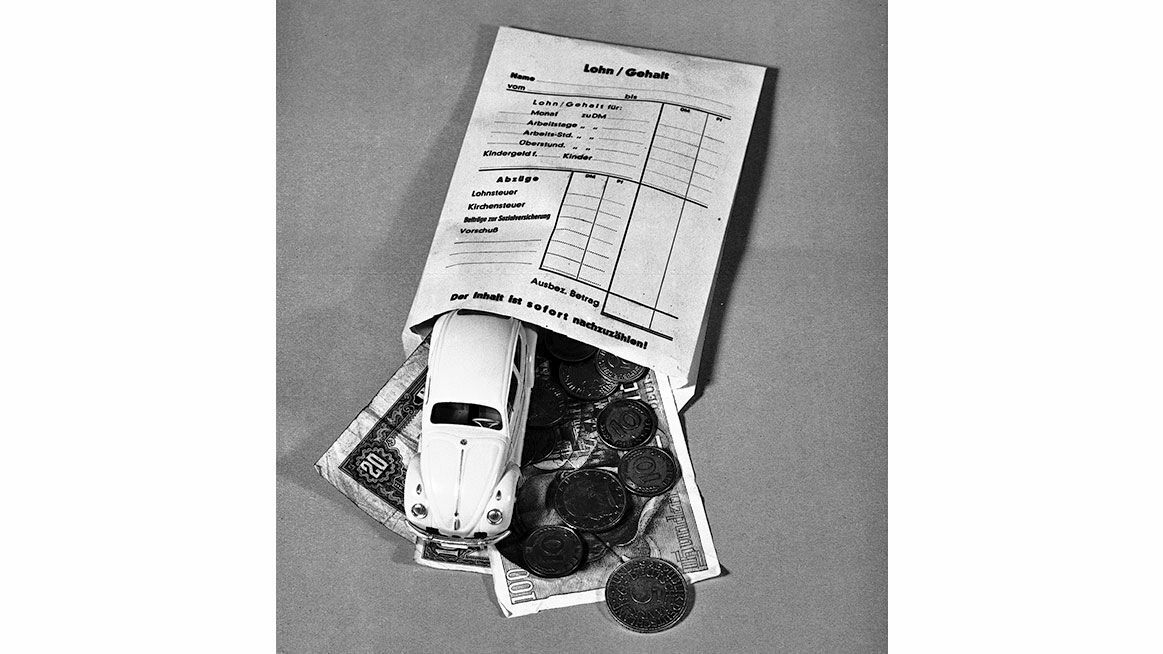

Volkswagen celebrated its greatest triumphs on the domestic market, where the saloon became a symbol of Germany’s Economic Miracle during the 1950s. The dream of mass motorisation that emerged around 1900 as the new technological age was born, and which was later misused by the Nazis for their own political ends, was finally being realised – and at a rapid rate. The Volkswagen saloon was the best-selling car of the decade, achieving a market share of around 40 percent. The model’s engineering and design imbued it with the sense of a “classless” product, embodying the self-confidence of an emerging consumerist society and reflecting the car’s transition from a luxury item to an essential part of daily life for broad segments of the population. The Transporter, built from 1950 onwards, was no less successful, dominating the van market with a share of about 30 percent. The sales potential for Volkswagenwerk GmbH on the domestic market was, nevertheless, limited. During the first half of the 1950s, backlogged demand from business users resulted in steadily growing sales, but the private customer base grew only slowly. Despite rising incomes, for most car-enthused West Germans the Beetle remained an unaffordable dream. Individual mobility was provided predominately by the motorcycle, and it was only in 1955 that new car registrations surpassed those of two-wheelers. The intensified restructuring of production to create a Fordist mass production system in 1954 appeared promising because international successes were making up for the limitations of the domestic market. Factory automation made possible the production volumes which were now needed to meet the demands of the recently entered international market and especially the boom in demand in the USA from 1954 onwards.

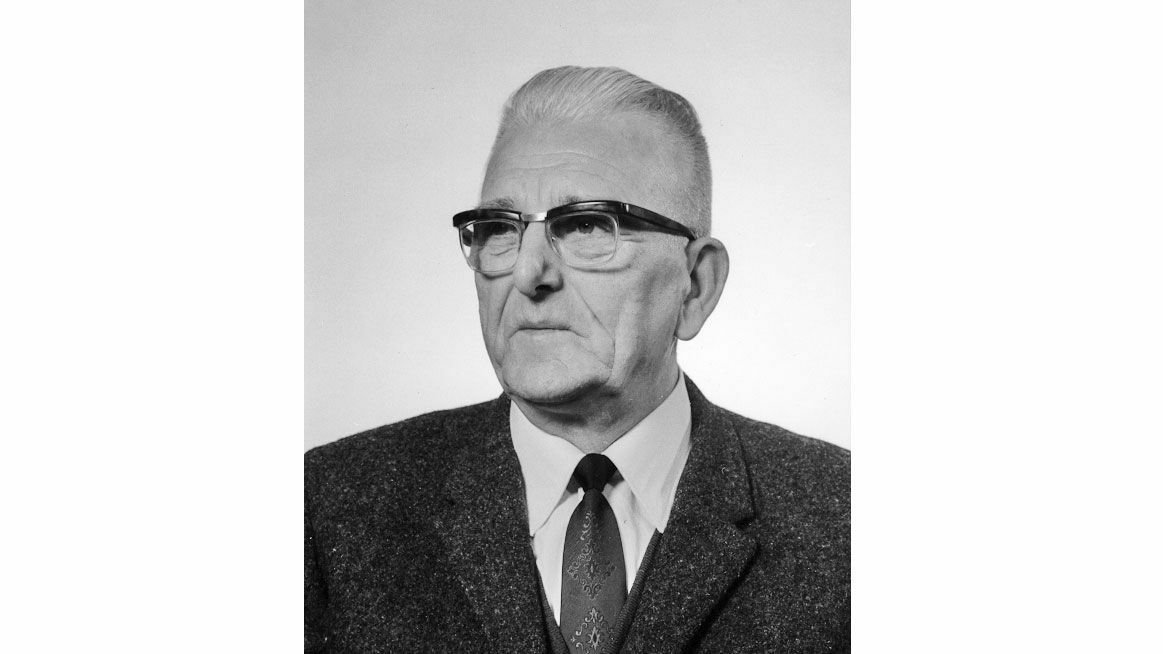

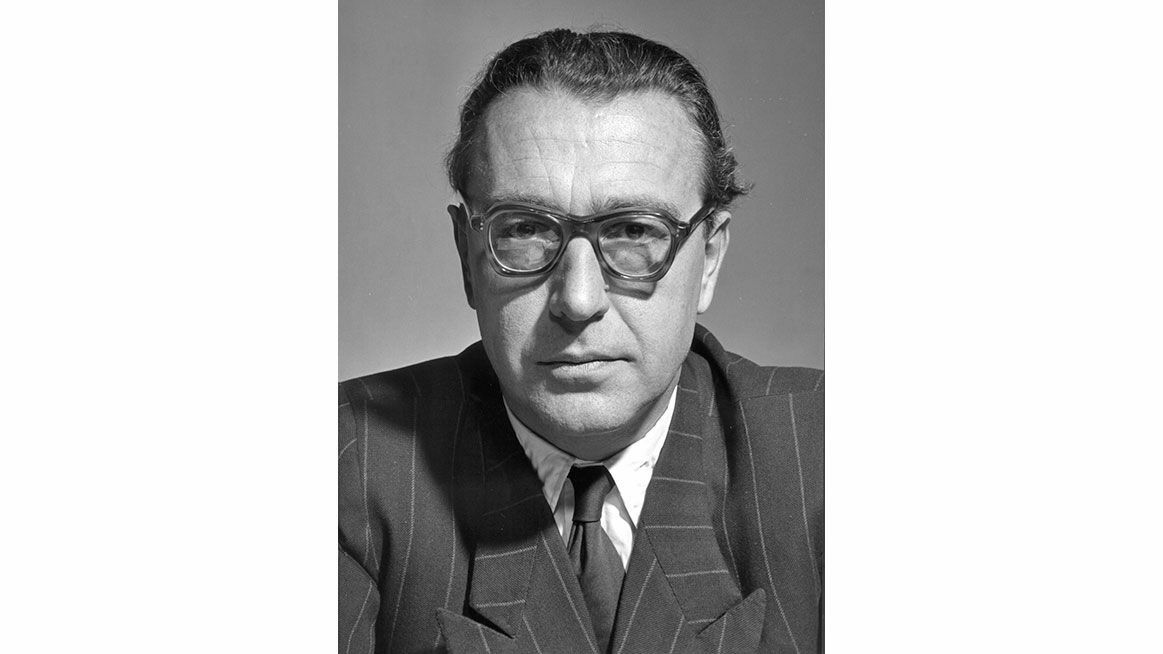

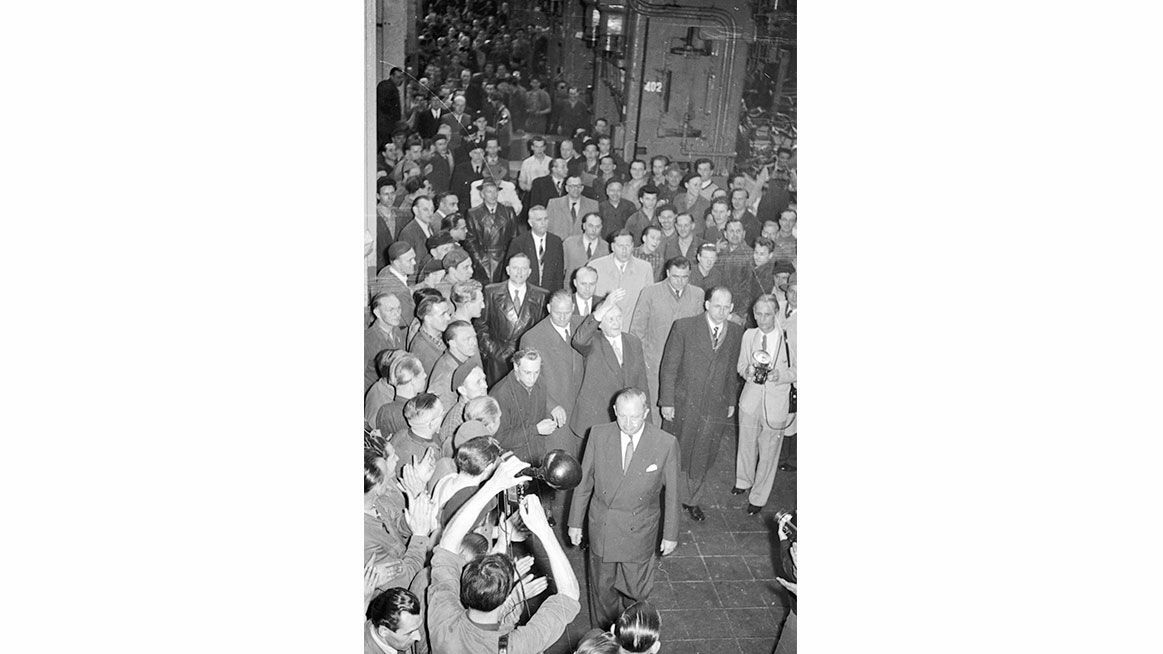

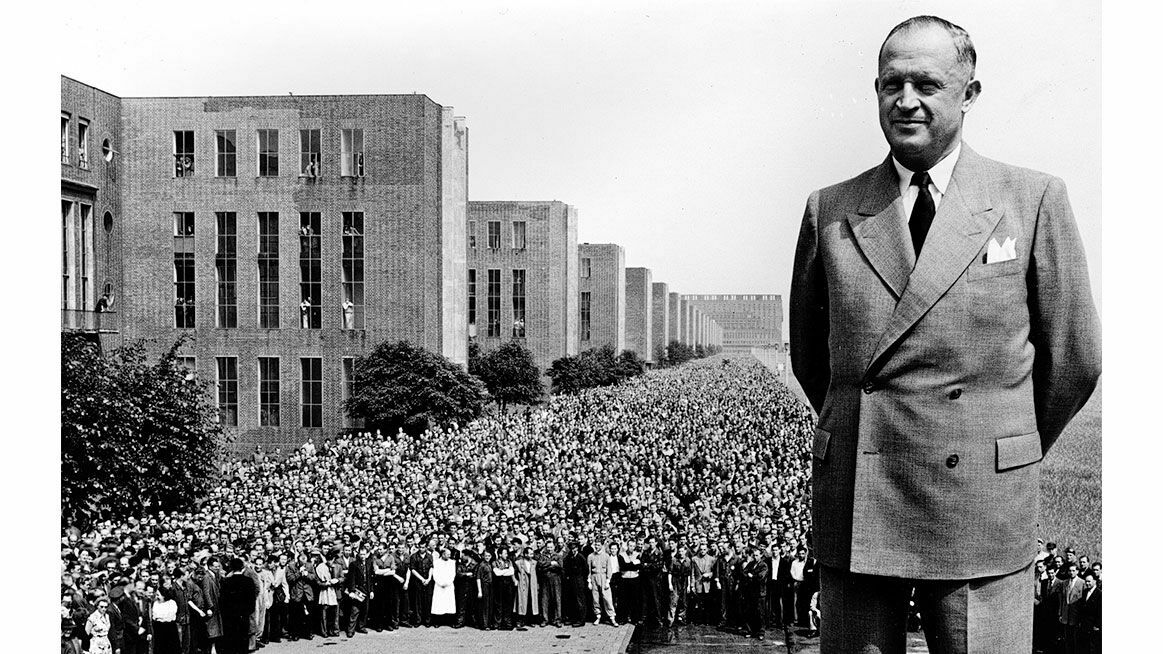

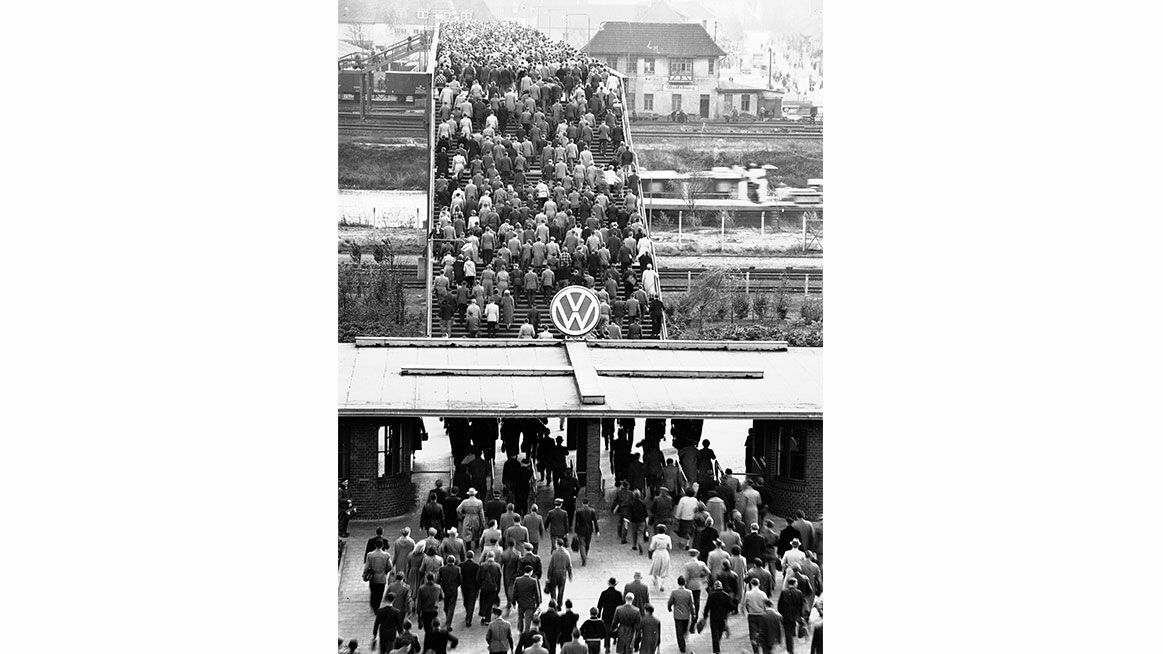

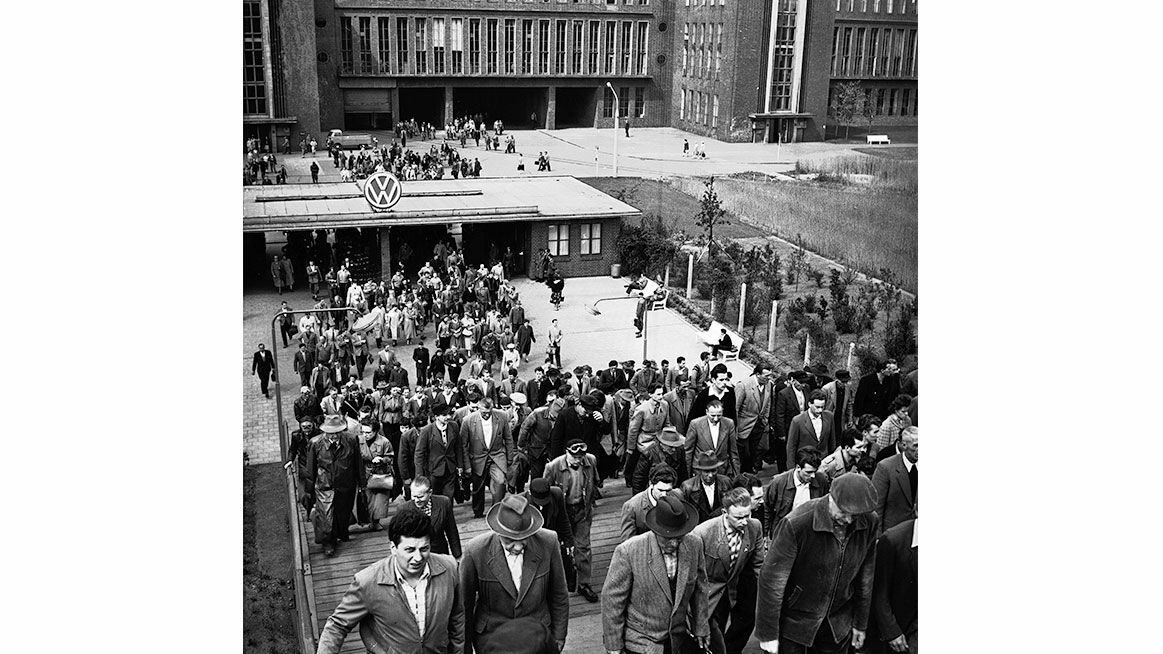

The workforce shared in the company’s economic success, earning high salaries and receiving a package of voluntary benefits which, against a background of generally peaceful industrial relations in the 1950s, engendered a co-operative working climate. There was a high degree of flexibility in work assignment. The Works Council and management worked together in an attempt to keep employee turnover to a minimum and solve the shortage of skilled workers. A generous pay and benefits system gradually helped to create a stable core workforce, with company employees considering themselves part of the Volkswagen family. Volkswagen’s pay rates were the best in the German car industry, and the company was a ground-breaker beyond its own sector too. Volkswagen’s policy of allowing employees to share in the company’s success was criticised by employers’ organisations, as well as by the Federal Government, which saw its anti-inflationary efforts as being endangered by such wage increases. Nevertheless, the company’s cautious public administration and excellent balance sheet gave the management of Volkswagenwerk GmbH enough leeway to steer its own course in terms of pay and working hours policy. In October 1955, the Works Council, the IG Metall metalworkers’ union and Volkswagen’s management agreed to a two-stage reduction in working hours, providing a 40-hour working week for most of the company’s employees from 1957 onwards.

Further disharmony between the company’s management and the German Federal Government surfaced on the privatisation issue, which the German parliament had been debating since the summer of 1956. Volkswagen’s management saw no urgent need to change the legal form of the successful business. The Works Council and the workforce, on the other hand, were interested in protecting the financial and fringe benefits they had received, and fought against the government’s privatisation plans. They received the support of the opposition SPD Social Democrat party, which raised its voice in parliament against the sell-off of national assets. Volkswagen’s management realised, however, that the privatisation of Germany’s most important car-maker was inevitable in the medium term. Volkswagenwerk GmbH was basically a company without an owner, administered by the State of Lower Saxony on behalf of and under the supervision of the Federal Government. In addition, public trusteeship did not conform to the free-market economy policies of the coalition government headed by the Christian Democrat CDU party.

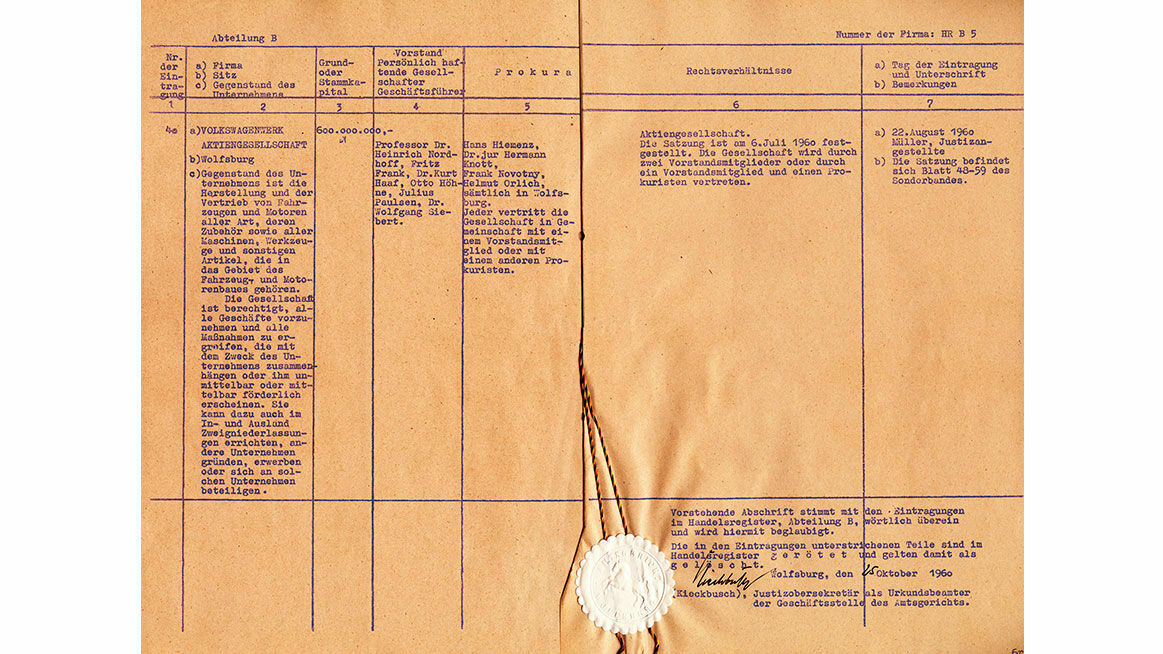

The Federal Government and the company’s management agreed that shares in Volkswagen should be sold widely as a “people’s stock”, so preventing large blocks of shares from being concentrated in a small number of hands. The proposed initial capital of DM 600 million provoked some opposition. With future investments in mind, Heinrich Nordhoff voted for cutting the share capital in half, but he could not push his commercially motivated position through. Volkswagenwerk AG, which was entered in the Register of Companies on August 22, 1960, was able to continue its successful development after privatisation. However, it was not the high share capital that caused the company difficulties during the 1960s, but rather the issues of mass production and model policy.