January 1

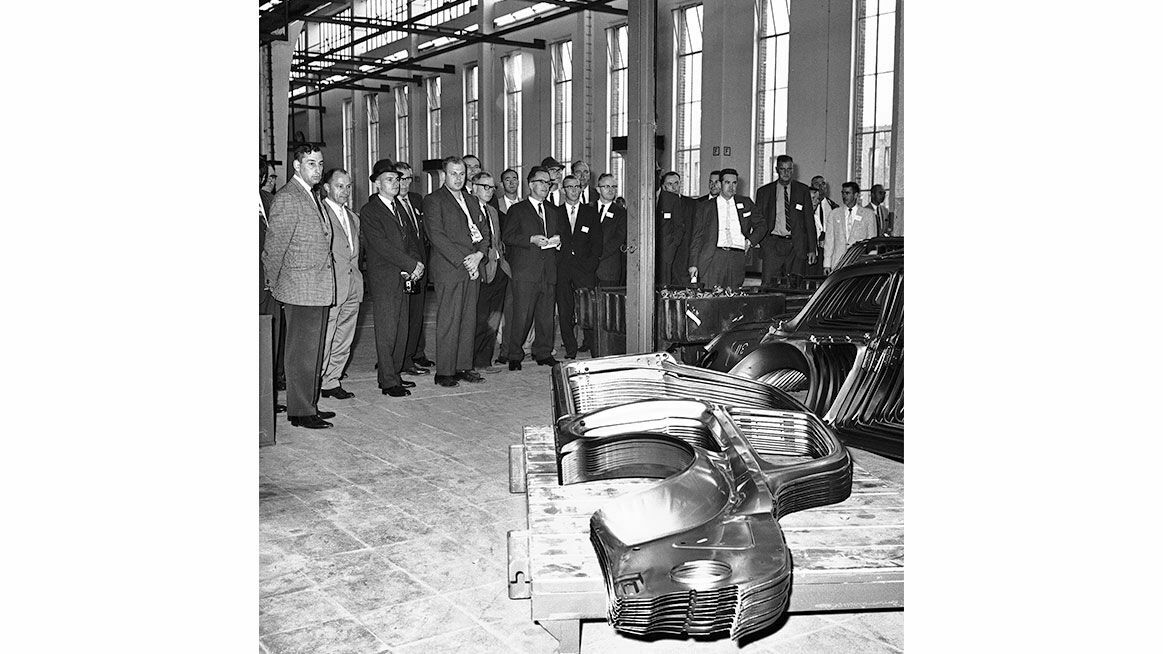

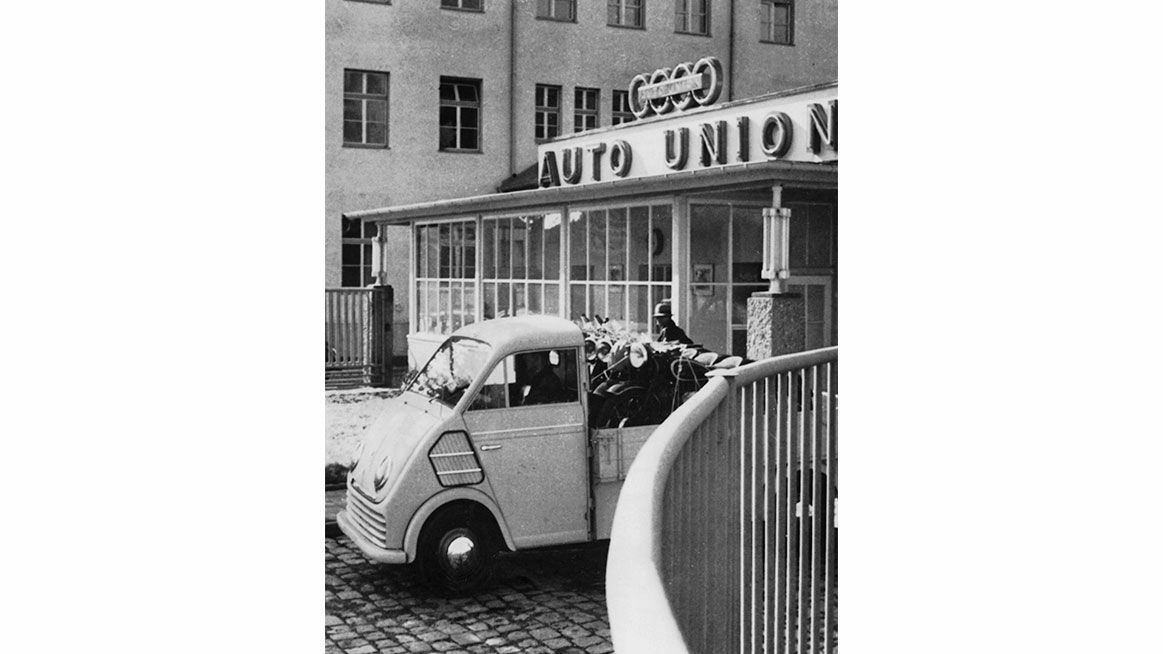

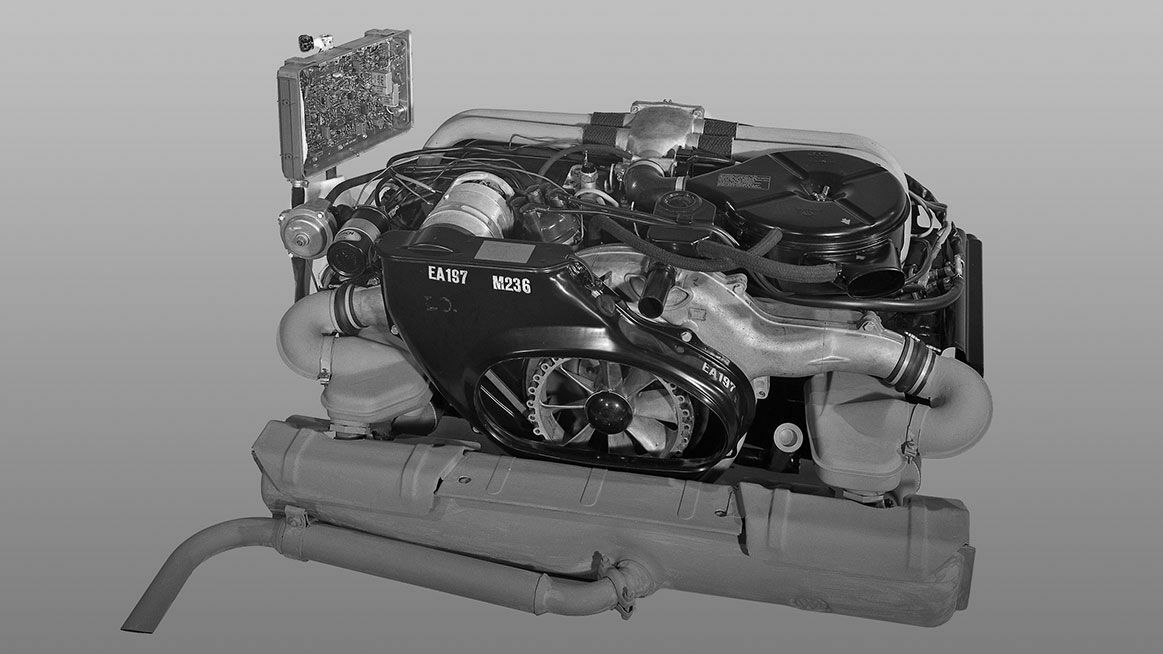

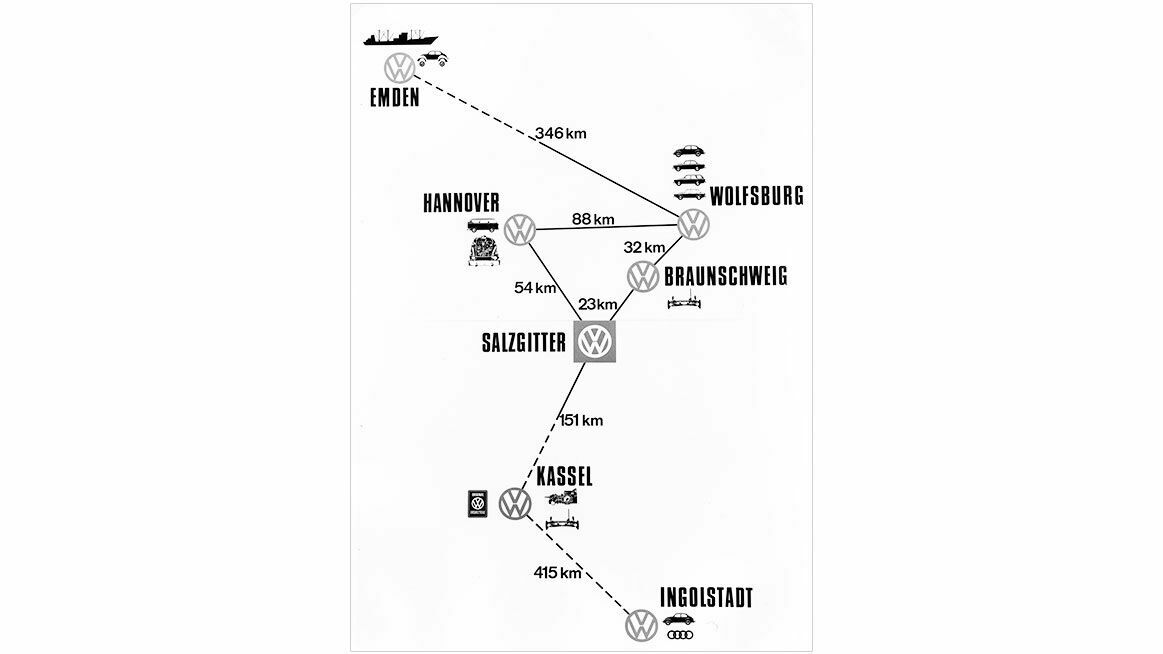

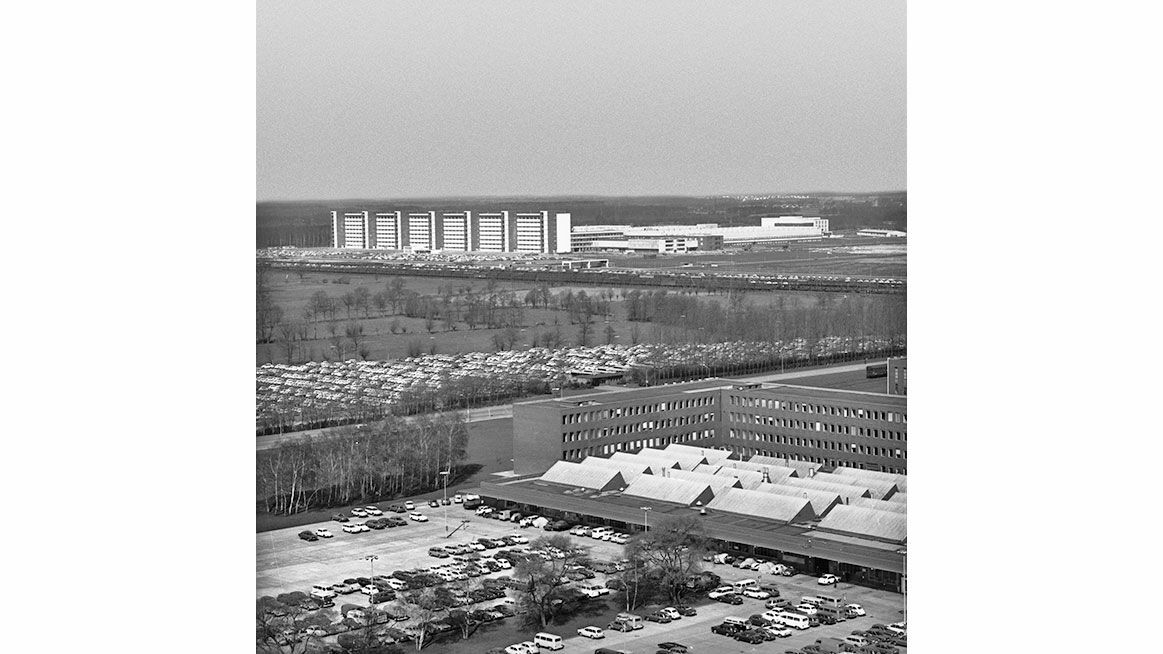

In order to improve competitiveness, Volkswagen examined the possibilities for co-operative ventures with Daimler-Benz AG. The restructuring undertaken in 1964 left the Wolfsburg car-maker with production of vehicles of less than 2 litre capacity. Volkswagen used the opportunity to acquire an initial 75.3 percent share in the Daimler-Benz subsidiary Auto Union GmbH on January 1, 1965. The business’s assets included a yearly capacity of 100,000 vehicles, 11,000 employees, a sales network with 1,200 dealerships and a new generation of engines. On the debit side, however, were large stockpiles of vehicles and a substantial financial crisis, because Auto Union GmbH was building a comparatively low-quality yet costly vehicle, which was consequently difficult to sell. Immediate organisational and model policy changes were needed to get Volkswagen’s new subsidiary out of the red. The Audi 72, quickly remodelled by the designers from the DKW F 102 and built at the plant in Ingolstadt starting in September 1965, failed to deliver a financial breakthrough. The model did, however, form the core of a new range maintained by Audi as an independent brand within the Volkswagen Group.

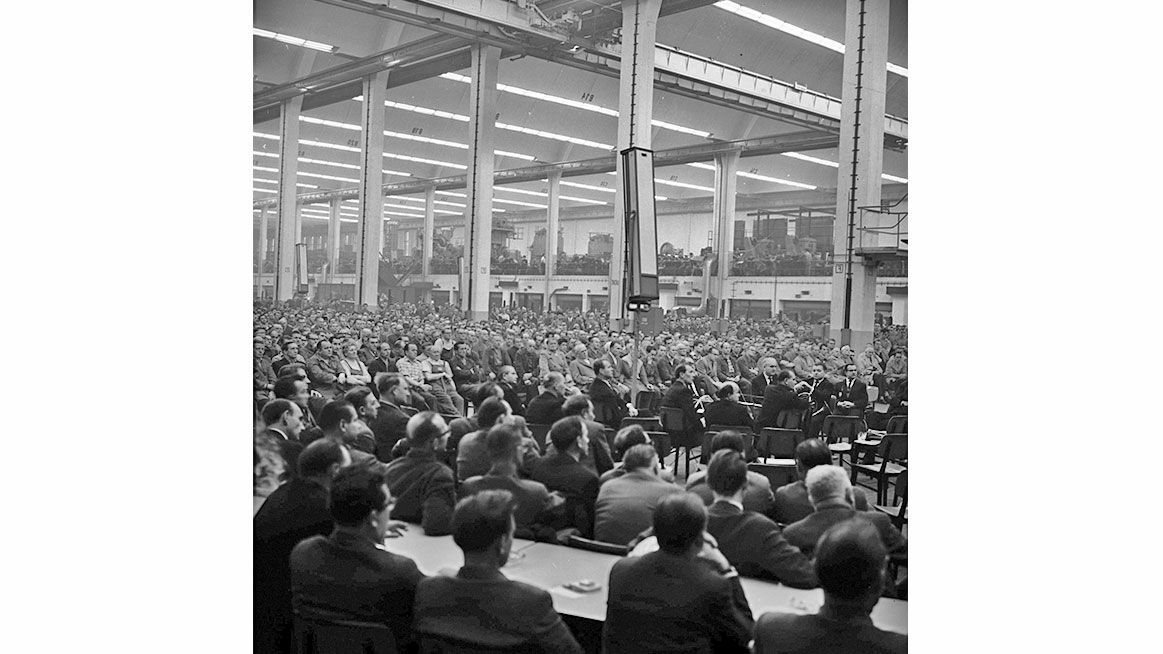

With reduced earnings, Volkswagen confronted the first post-war recession in 1966/67, which heralded the end of an exceptional and protracted phase of prosperity and the return to normal economic conditions. Declining demand on the domestic market forced the company to reduce the number of vehicles manufactured in 1967: Type 1 production was cut by 14 percent and that of the VW 1600 by 35 percent. Although both the economy in general and Volkswagen’s sales figures were improving by the end of the year, the brief selling crisis had a lasting impact.

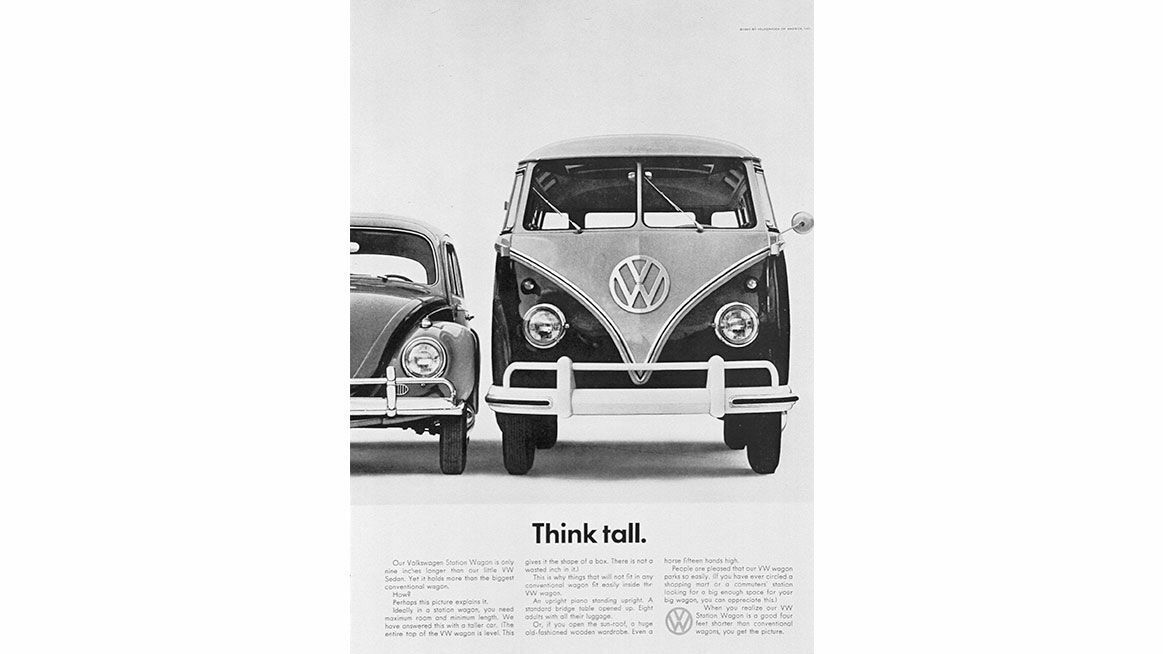

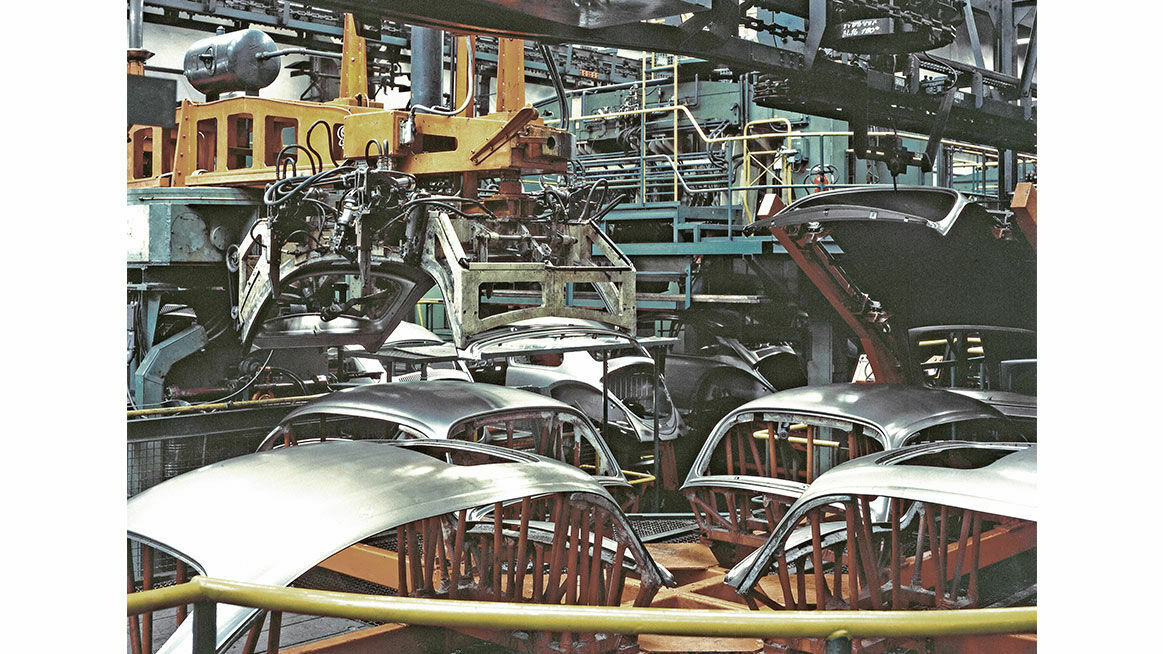

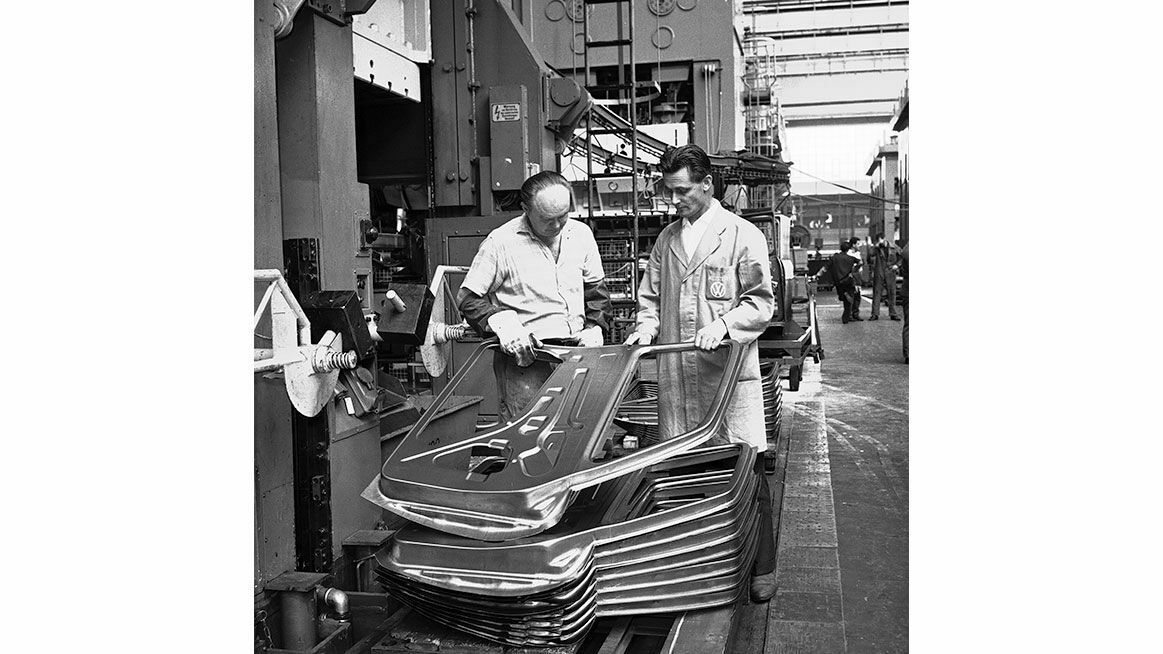

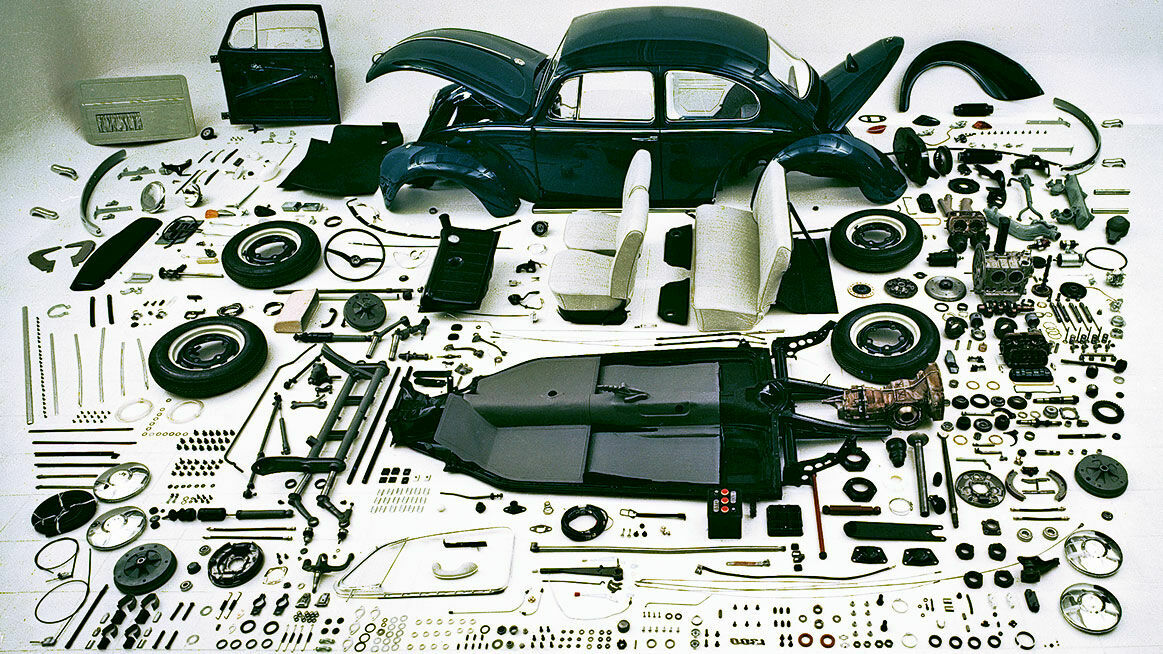

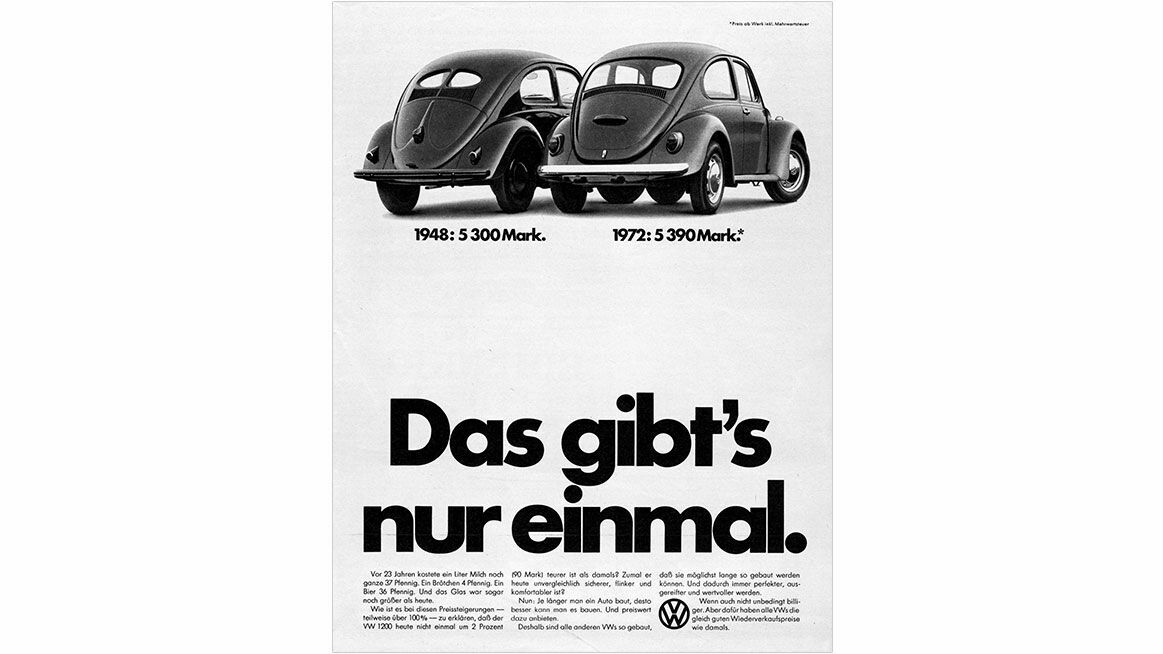

It demonstrated the economic susceptibility of large-scale mass production, which was coming under additional pressure due to changes in production and model policy. The production depth now achieved and the wide variety of models and variants built up by the company over the previous years had led to a decrease in productivity and reduced the company’s efficiency. Volkswagen’s main competitive advantage – the mass production of one model – now threatened to become a serious disadvantage. Increasing motorisation and greater competition on key markets reduced the possibility of compensating for lost income by growing sales as had been done before or by raising prices.

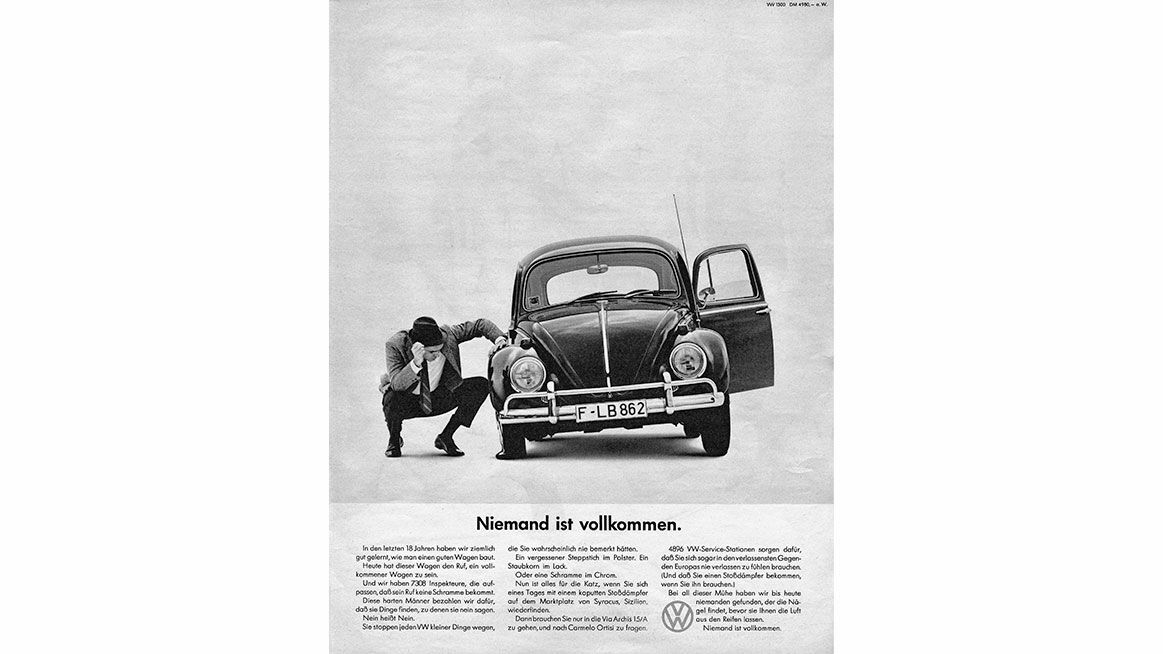

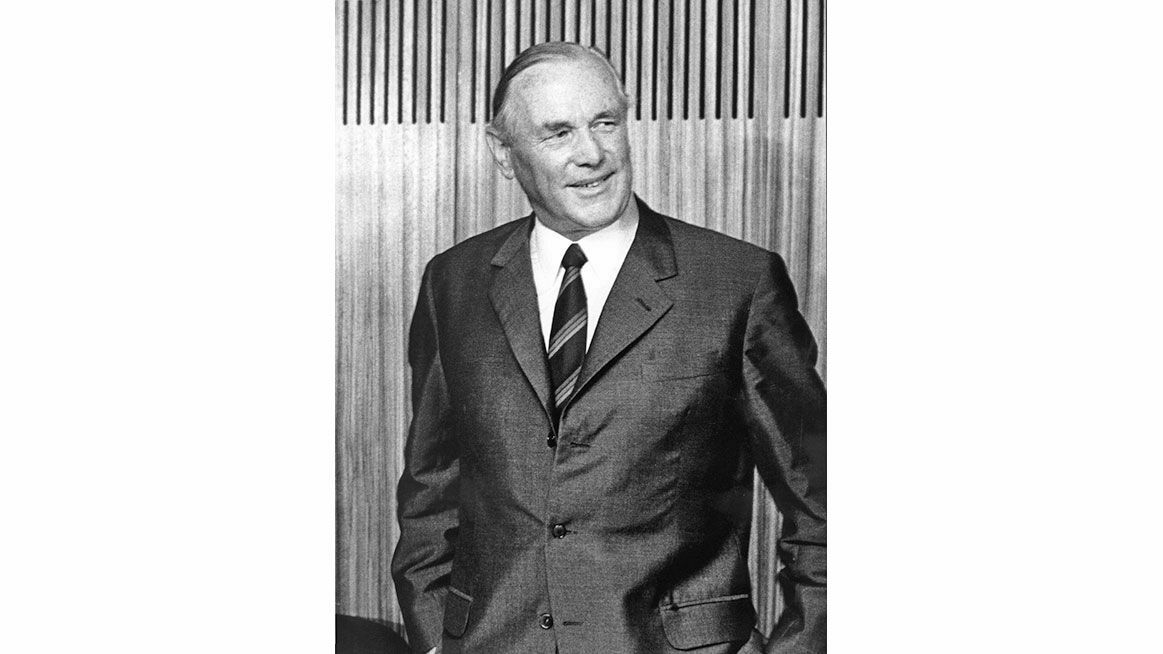

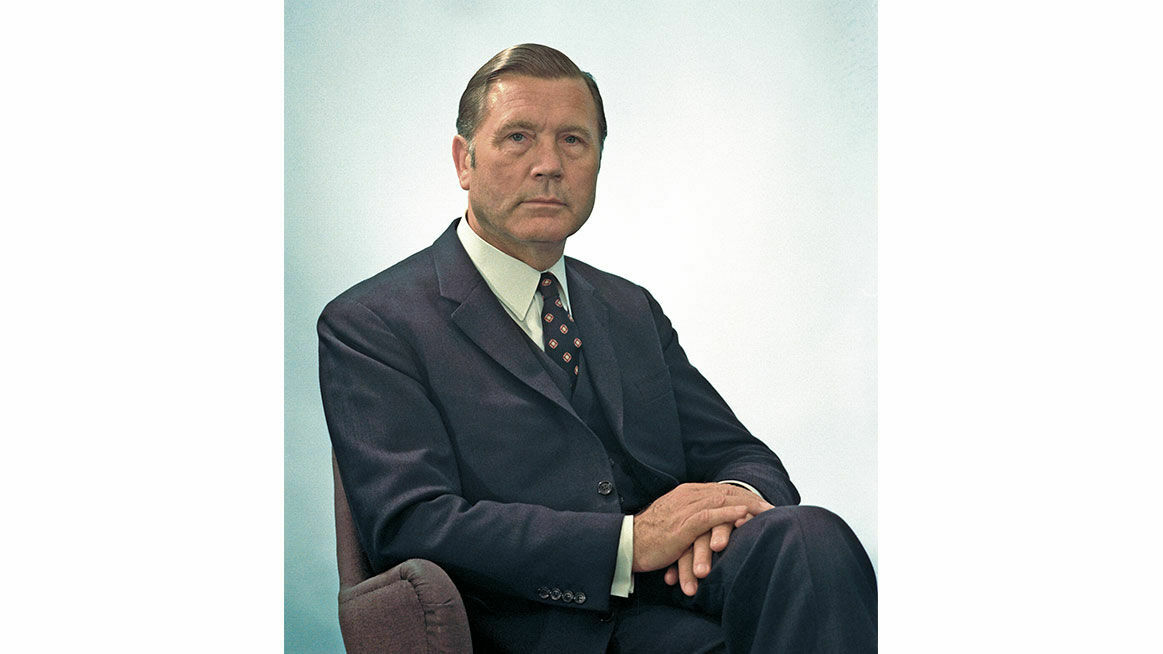

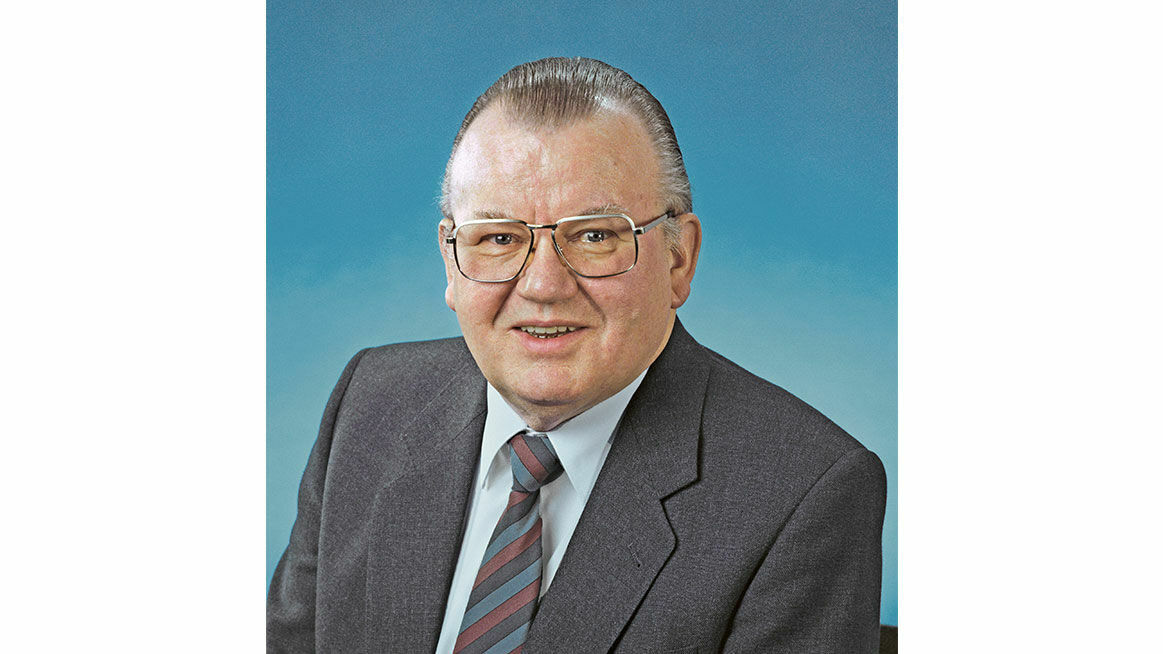

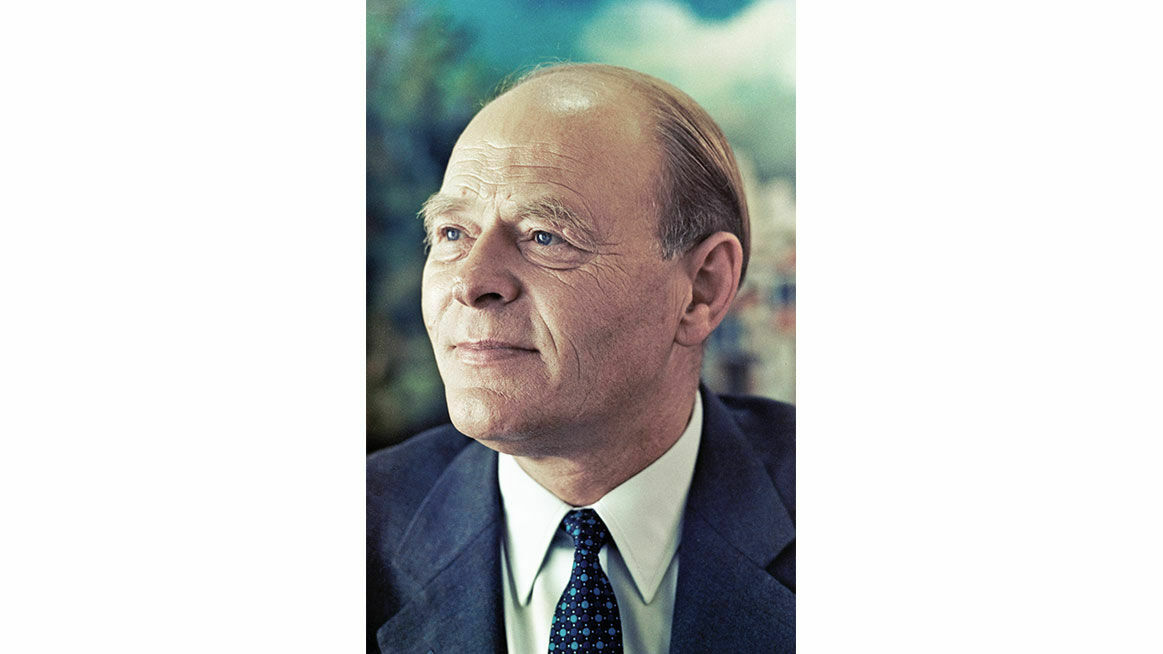

It was during this period of radical change that the Heinrich Nordhoff era ended. His commitment to the Volkswagen saloon, which during his 20-year leadership was technically perfected, as well as to the combination of mass production and global market orientation had led Volkswagen to the pinnacle of the European car industry. In order to maintain that position, far-reaching changes were necessary after Nordhoff’s death.

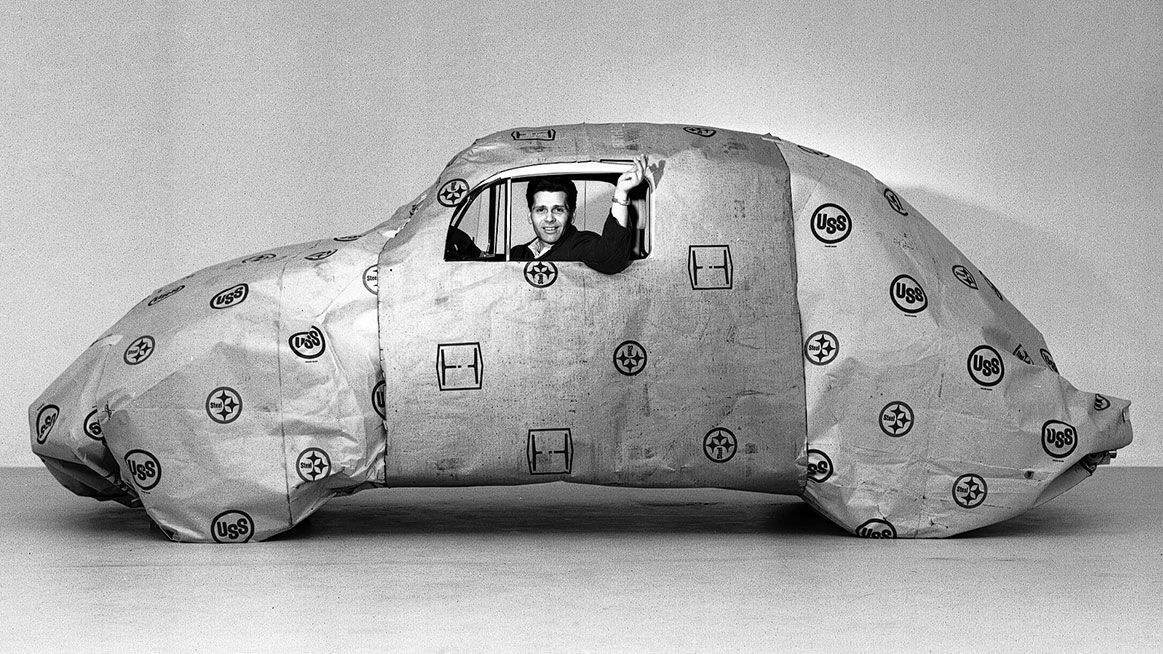

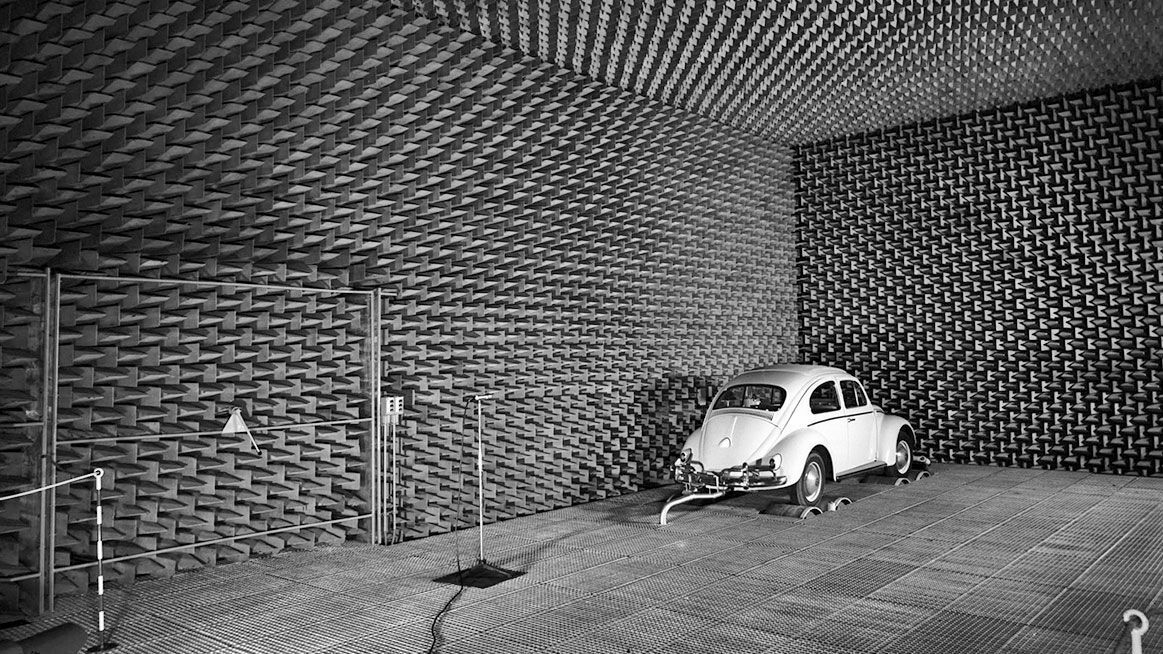

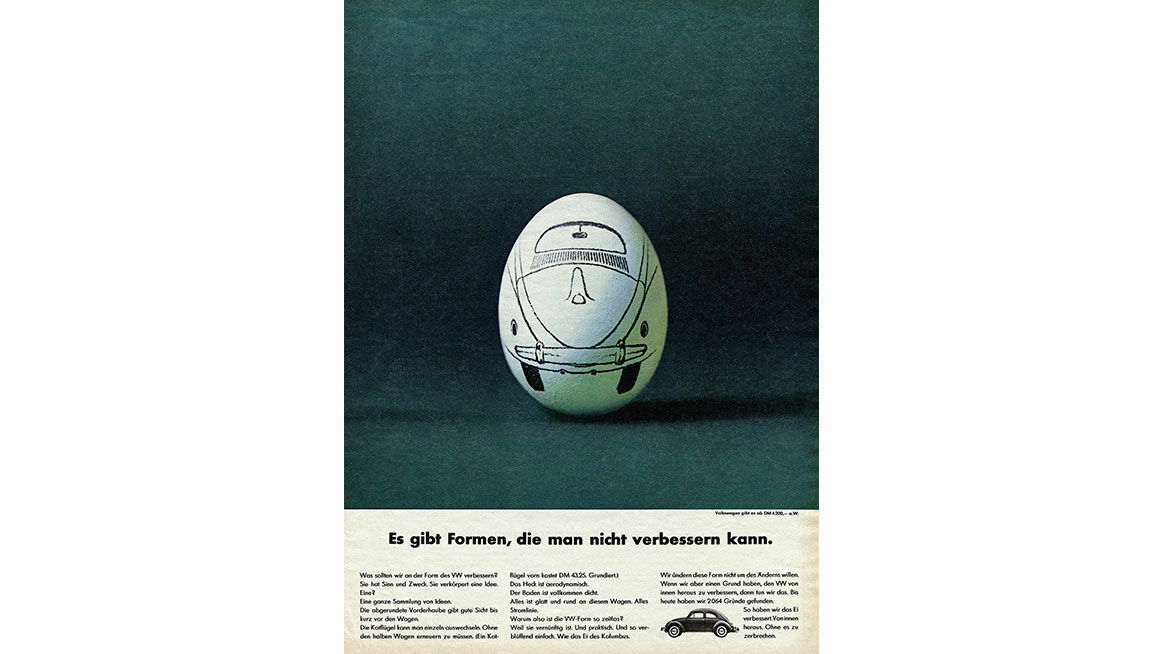

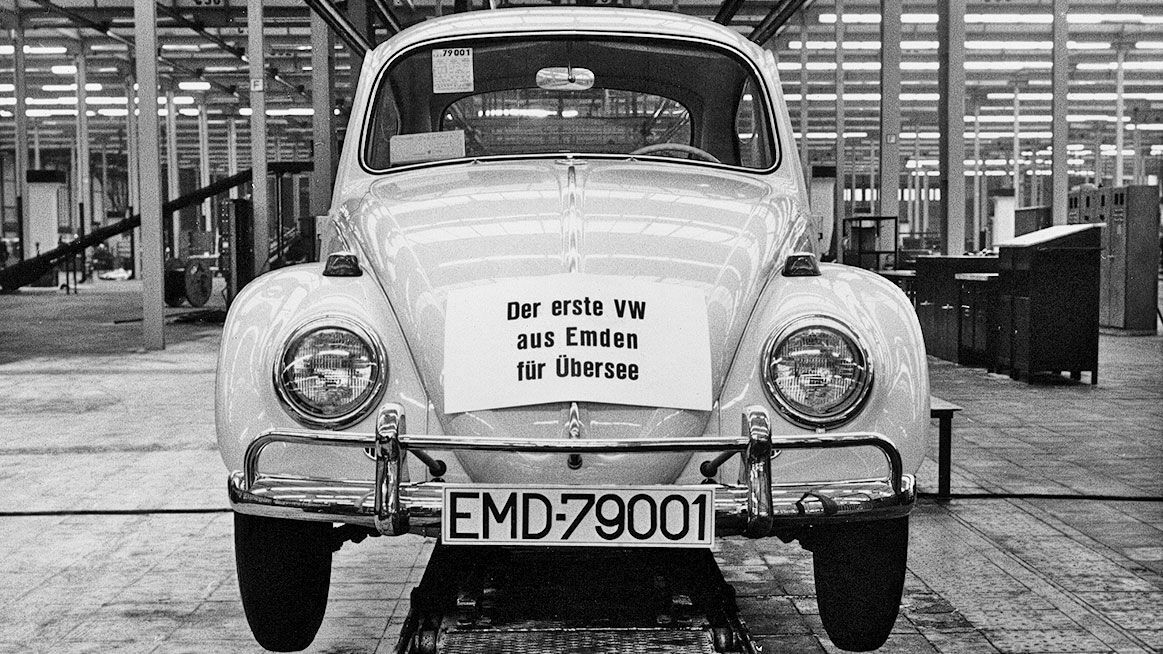

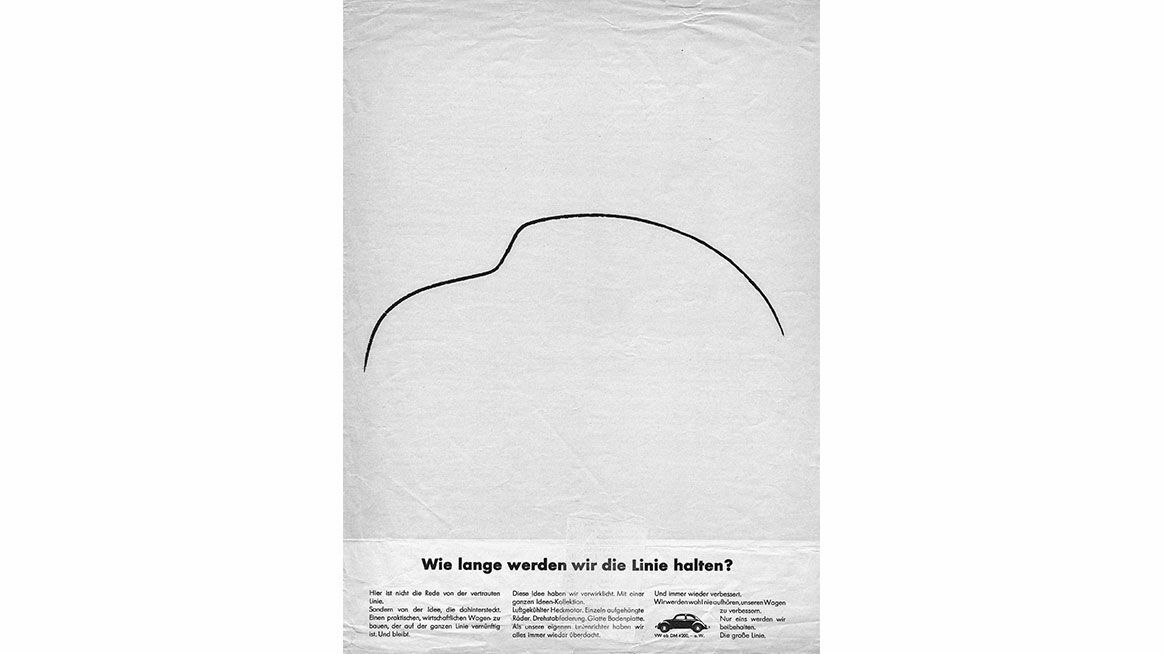

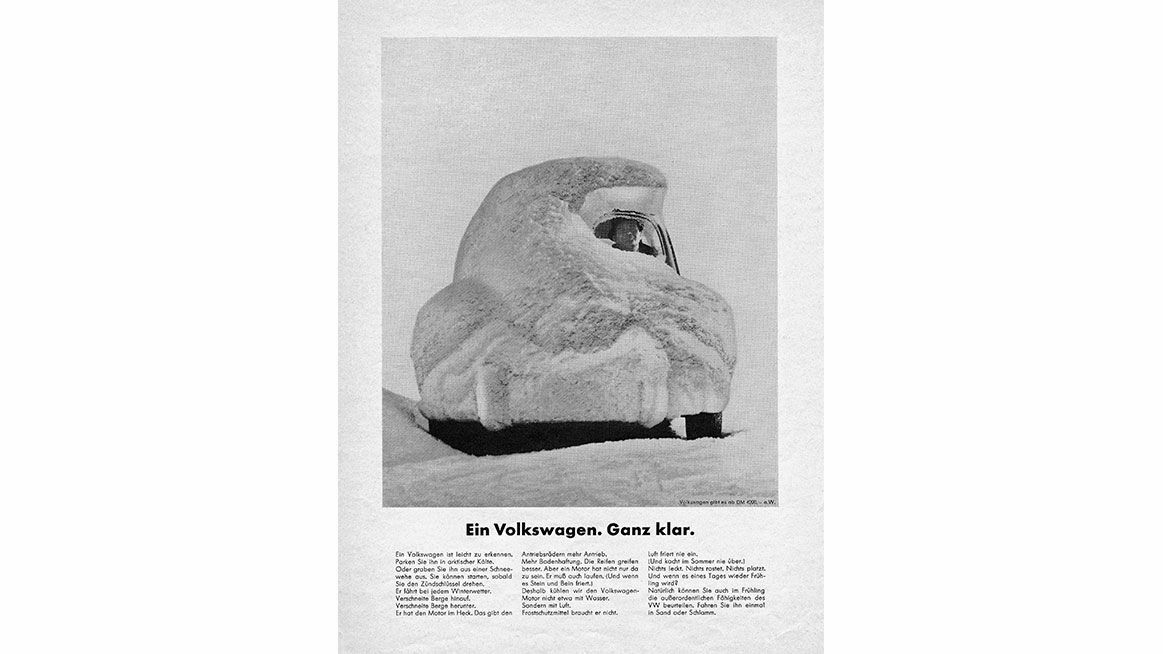

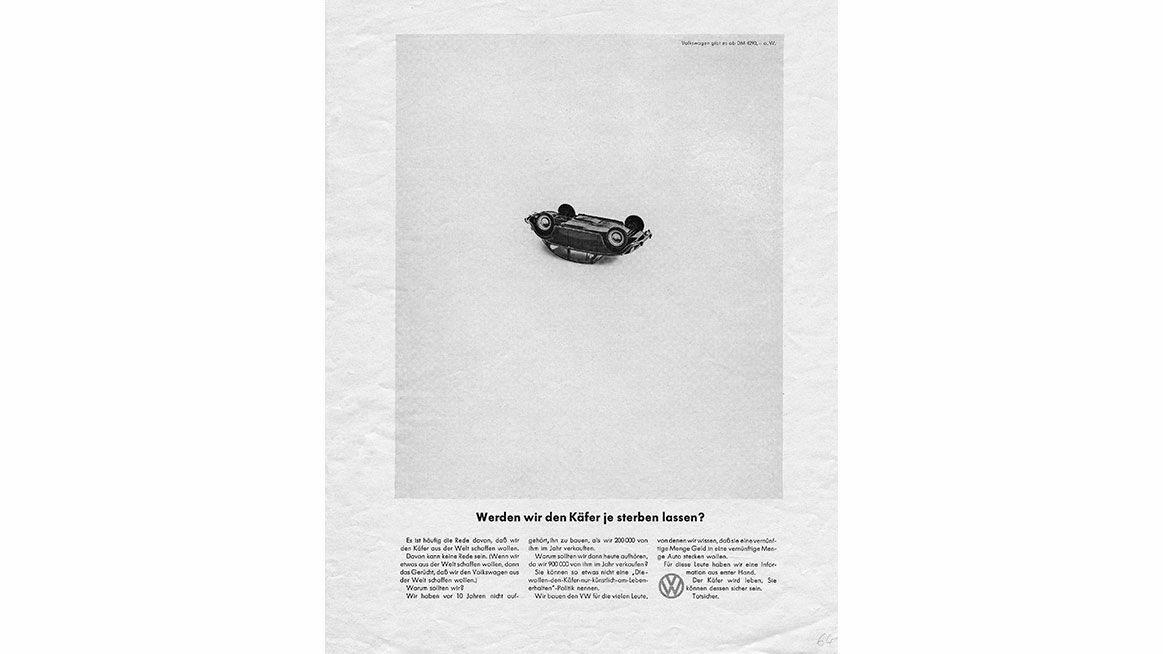

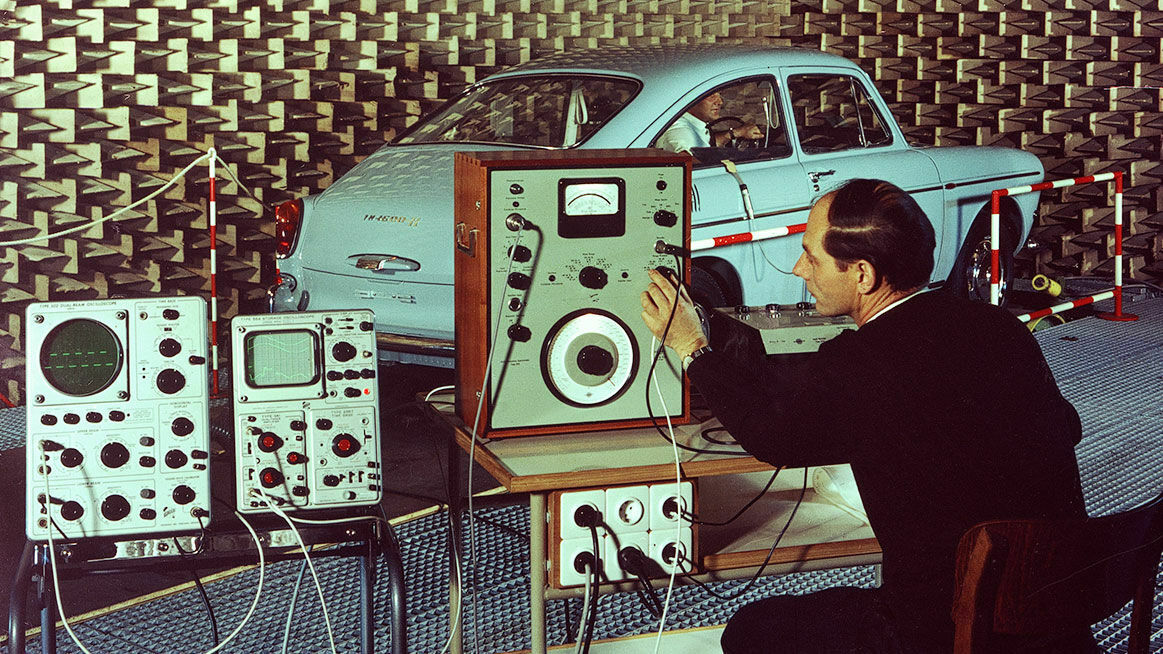

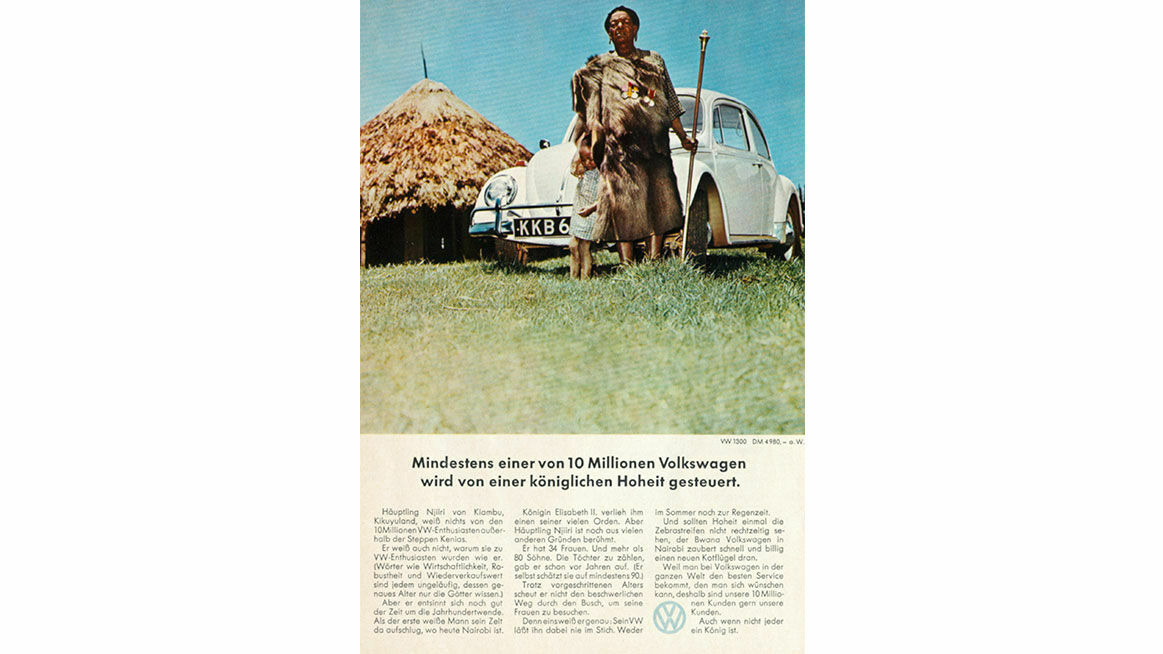

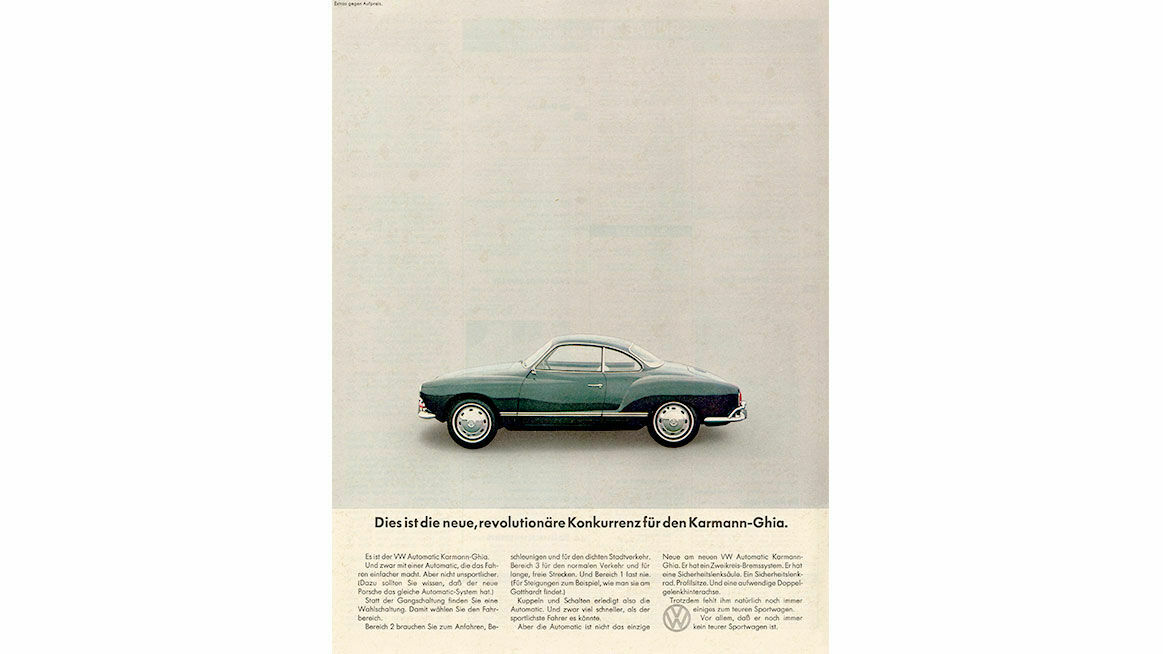

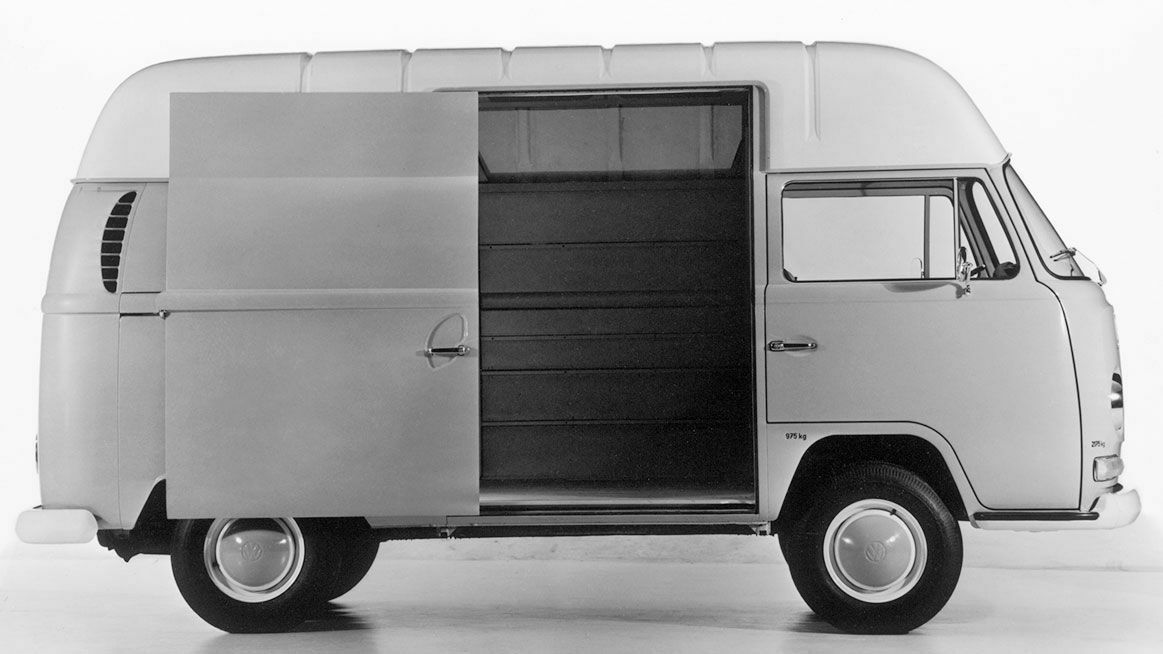

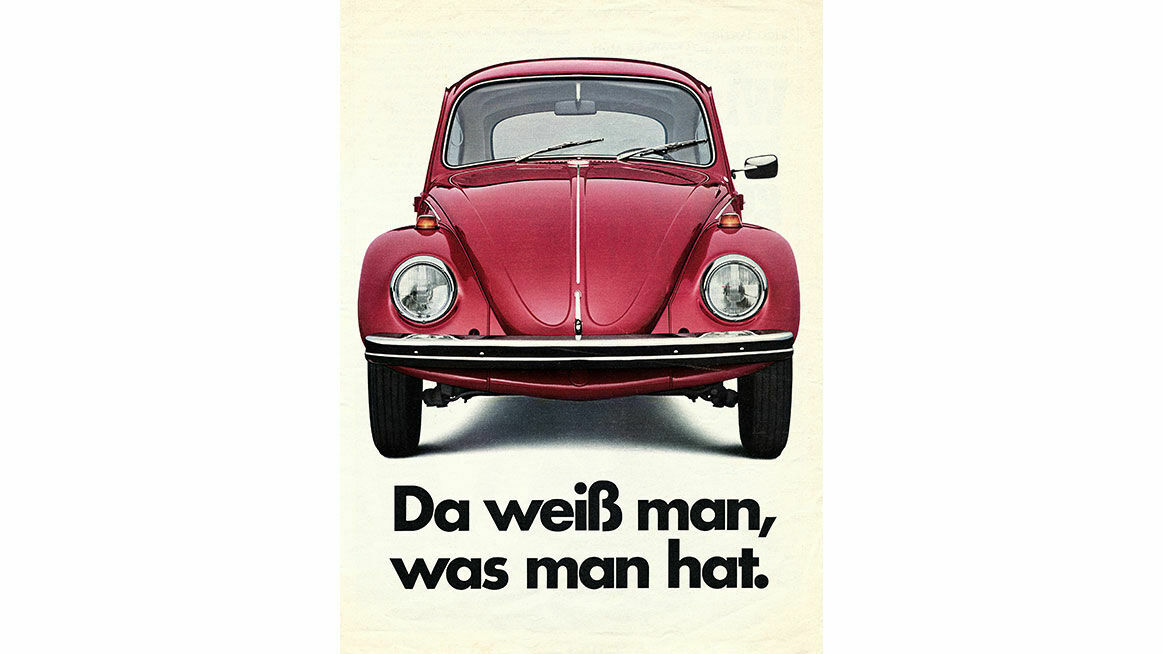

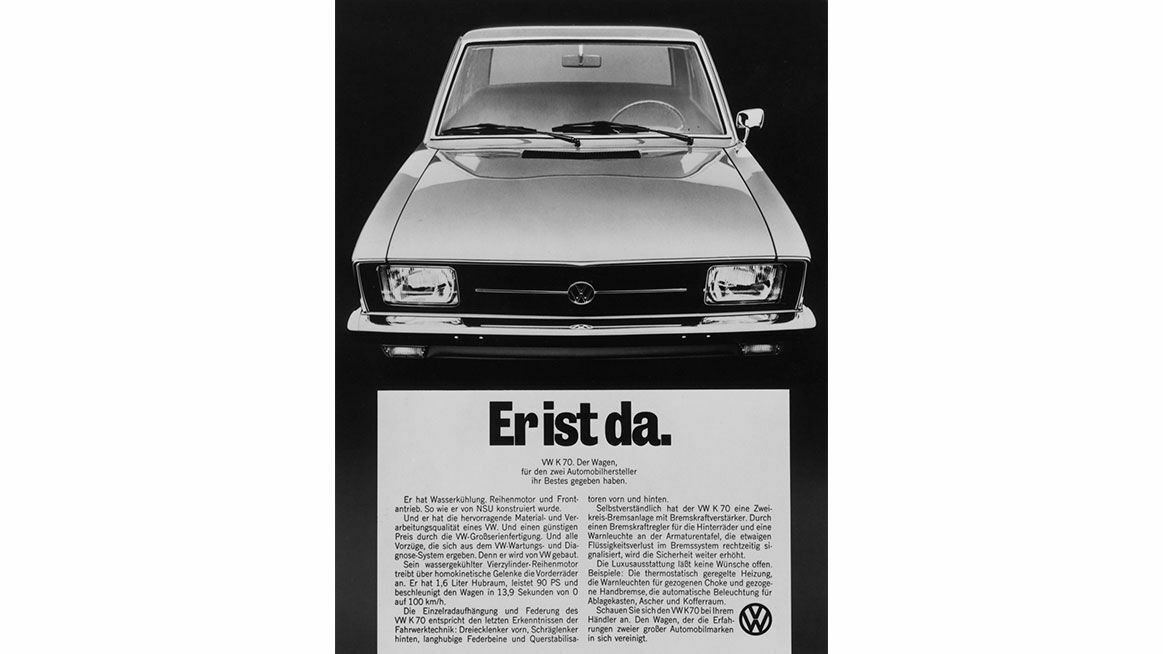

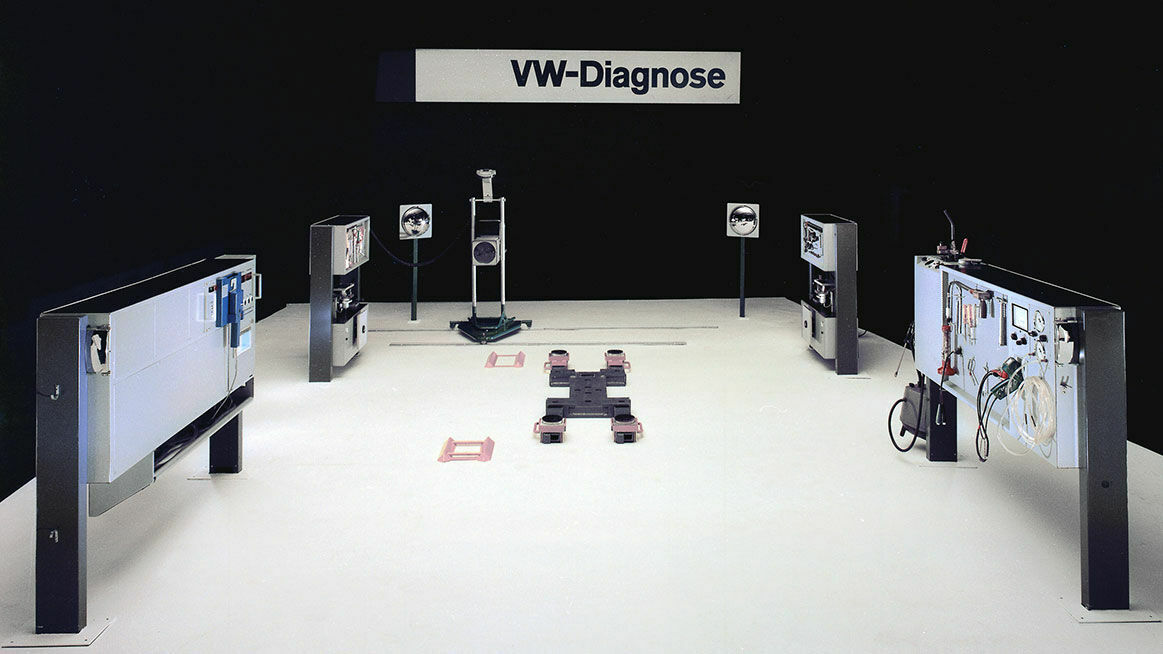

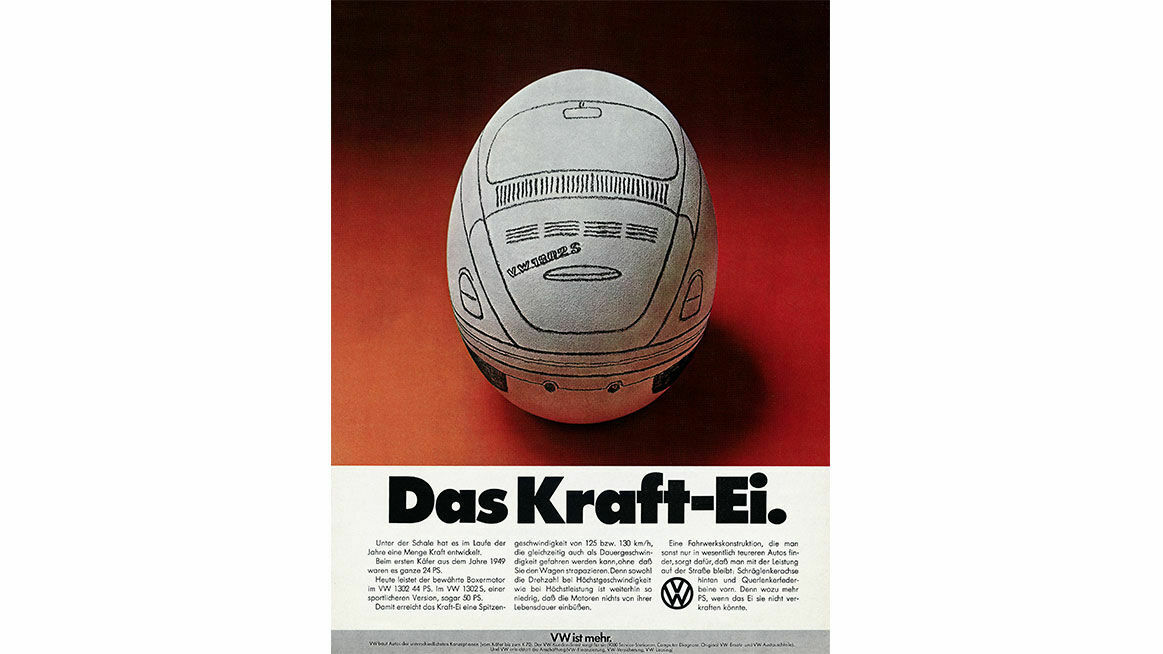

Volkswagen introduced a number of cost-cutting measures in 1968 aimed at improving yields. Along with the rationalisation of production, the company invested in expanding research and development, reasserting the importance of those functions. Greater focus was placed on the recruitment of technicians and engineers and the systematic development of management staff. With the start of production of the VW 411 in September 1968, the Wolfsburg car-maker continued to move away from its dependency on the Type 1. However, with its daily production of 4,200 units, that model still remained the lifeblood of the company. In order to maintain its competitiveness, Volkswagen developed the VW 1302, featuring a new chassis and twice as much boot space, which went into mass production as a saloon and convertible in 1970. All the efforts made could not, however, prevent the Type 1, with its air-cooled rear-mounted engine, from losing its appeal. A new generation of small and mid-sized cars with water-cooled engines, front-wheel drive, lots of interior and boot space and new styling was conquering the market. Sales of the Type 1 dropped after 1970, though the losses were balanced by the success of the South American subsidiaries and of the now merged Audi NSU Auto Union AG, whose models served a growing market segment. Volkswagen concentrated its activities on the urgent task of developing a new range of products.

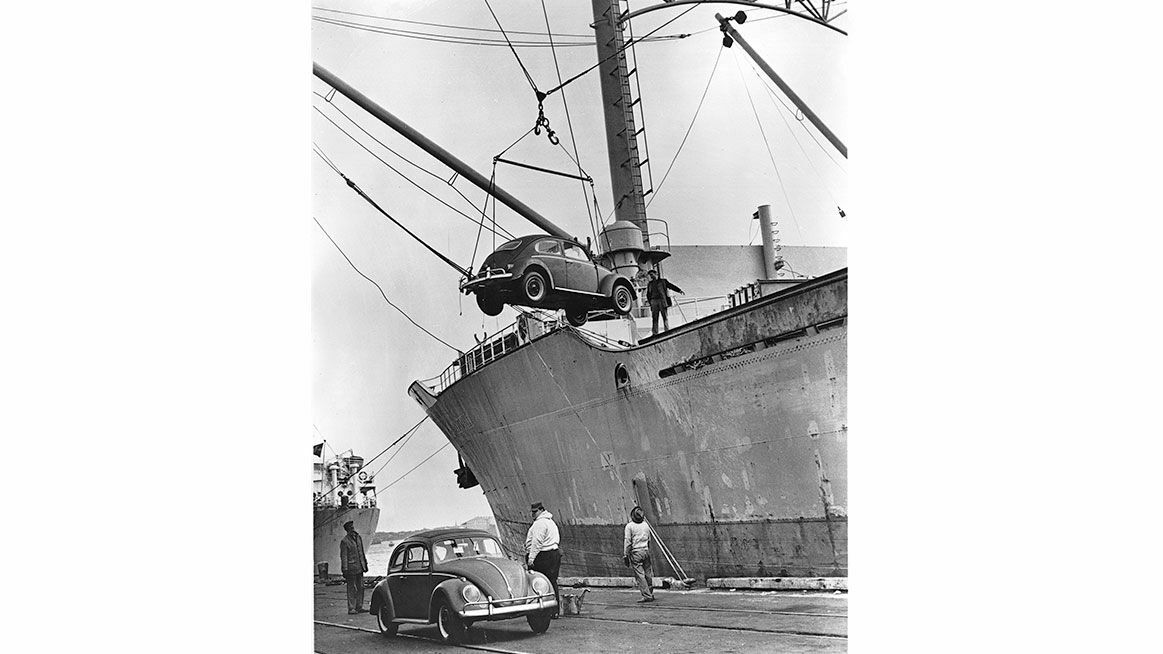

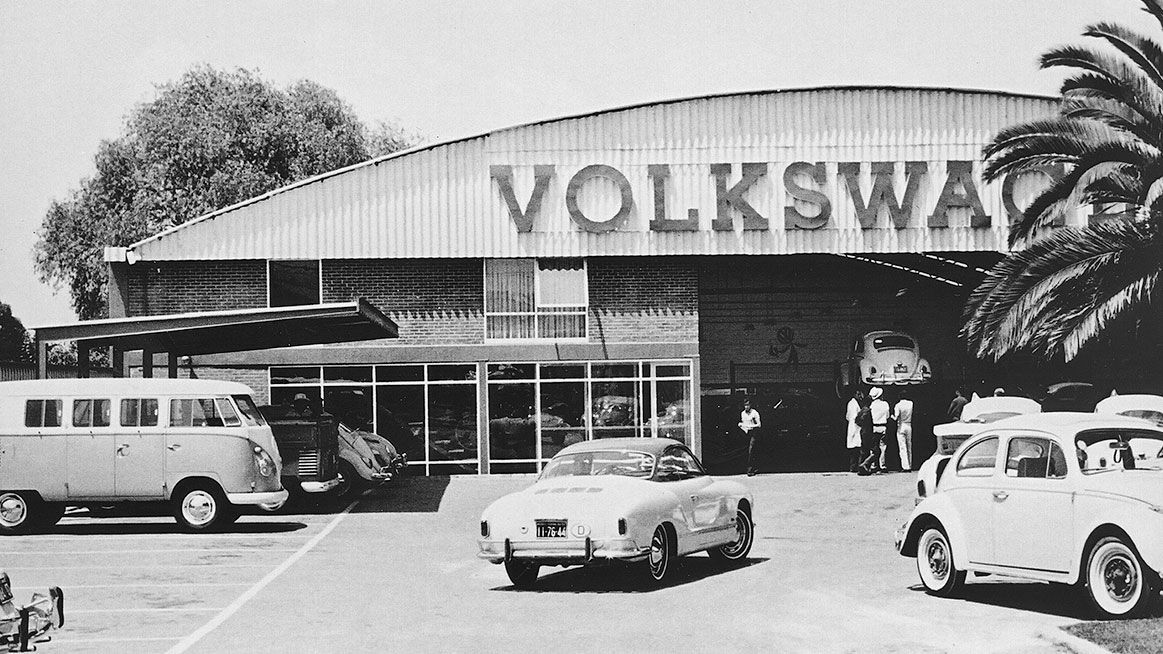

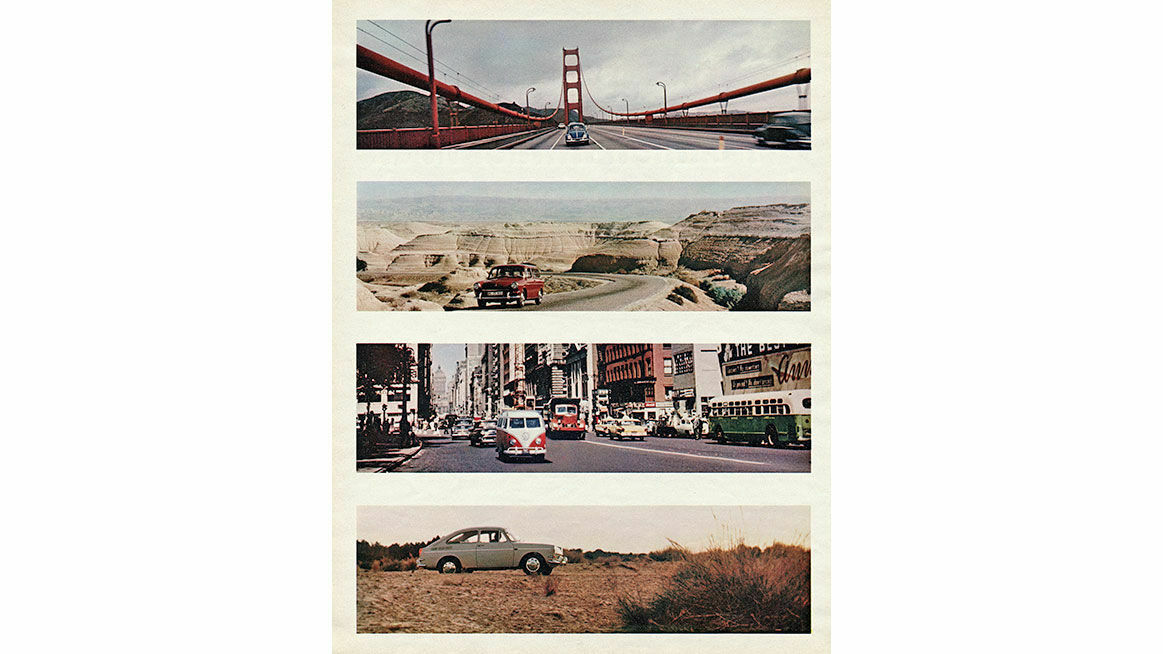

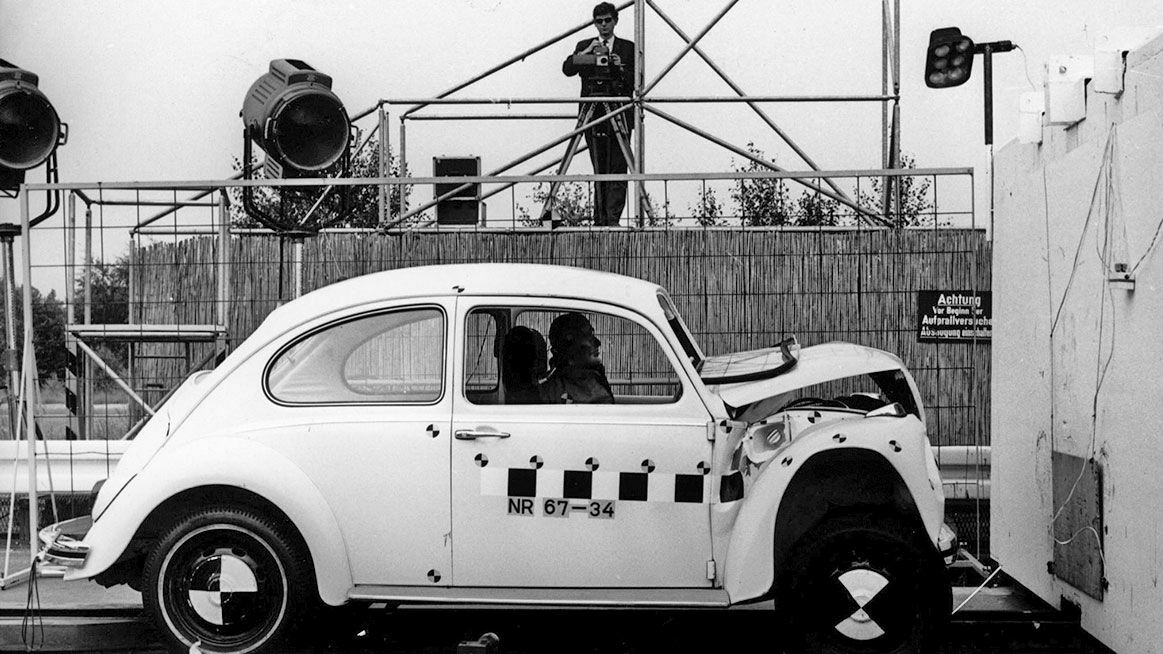

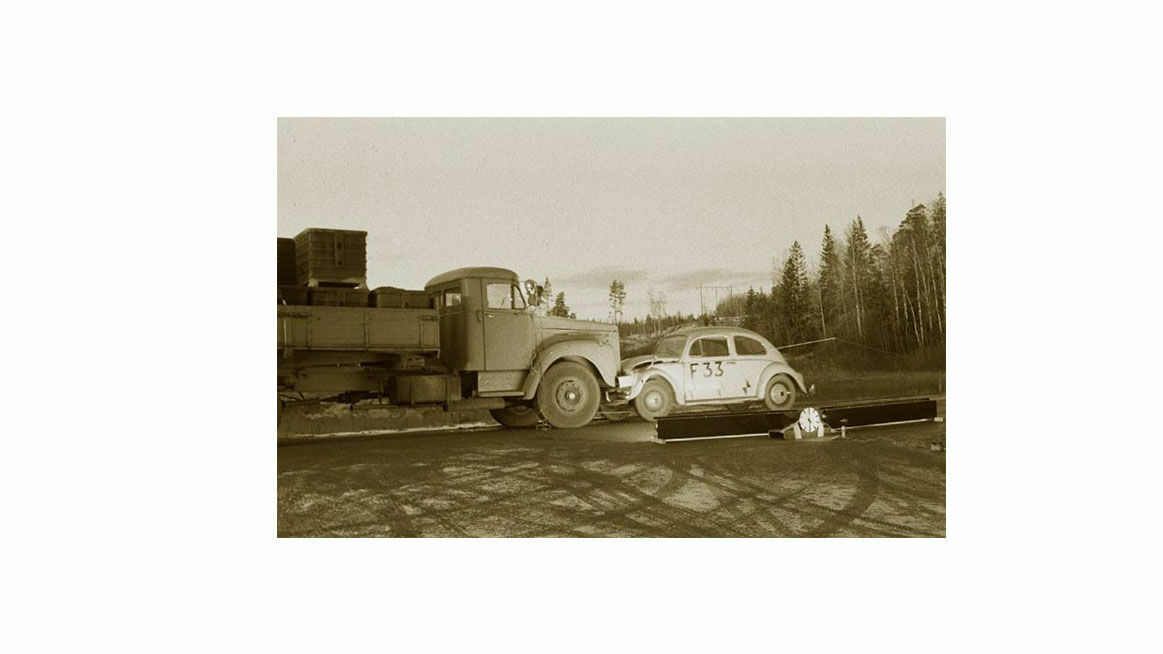

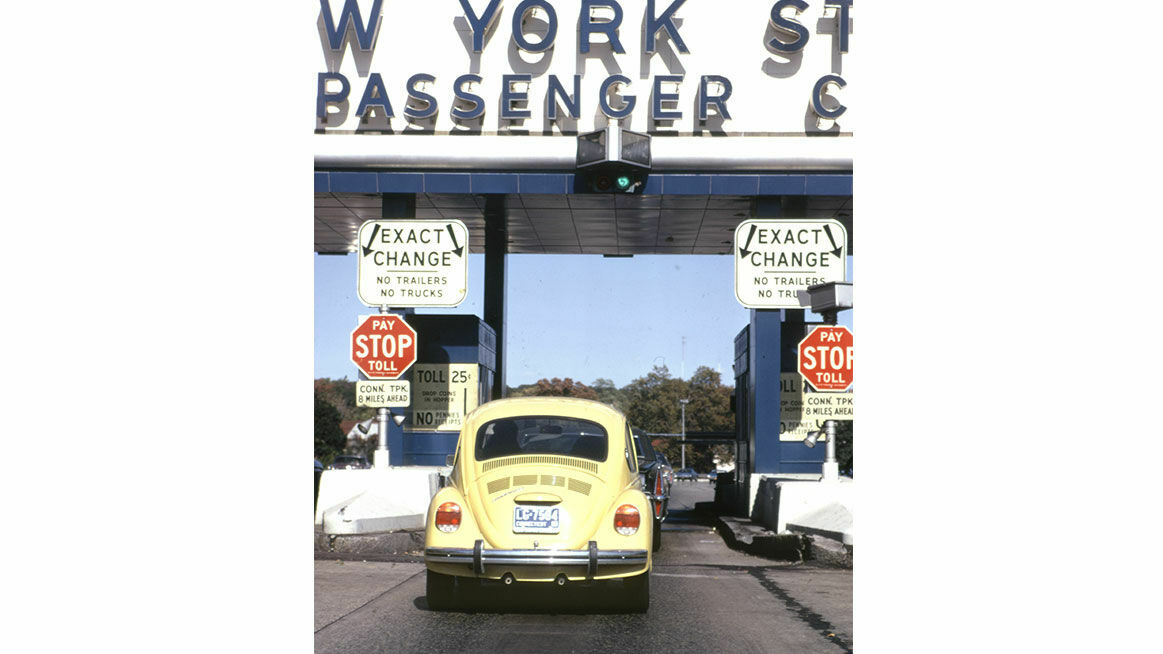

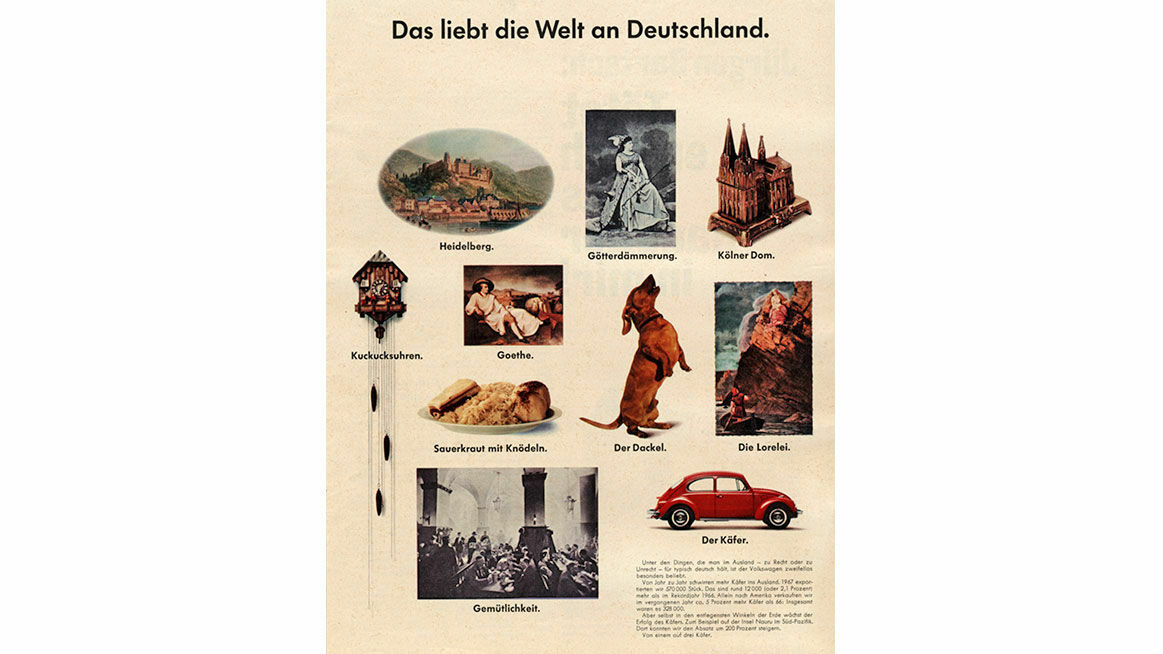

Sales problems also arose abroad, intensified by the relaxing of exchange rate controls. The revaluation of the Deutschmark impacted on Volkswagen exports and led to stronger competition from foreign car-makers on the domestic market as demand fell. Volkswagen responded to changes in exchange rate policy by increasing prices, especially as higher production costs and lower yields left little leeway for any other course of action. As a result, prices increased relative to other car-makers, and the company’s competitive position on key volume markets deteriorated. This was true in particular of Volkswagen’s exports to the USA, the main export market, where Volkswagen of America’s profits and sales were curtailed by exchange rate linked cost handicaps compared to Japanese and US car-makers. Between 1970 and 1972, Volkswagen of America’s sales dropped from about 570,000 vehicles to just under 486,000. To make matters worse, the Beetle’s popularity among Americans began to decline as the model failed to keep up with progress in terms of drive technology, fuel economy and safety.

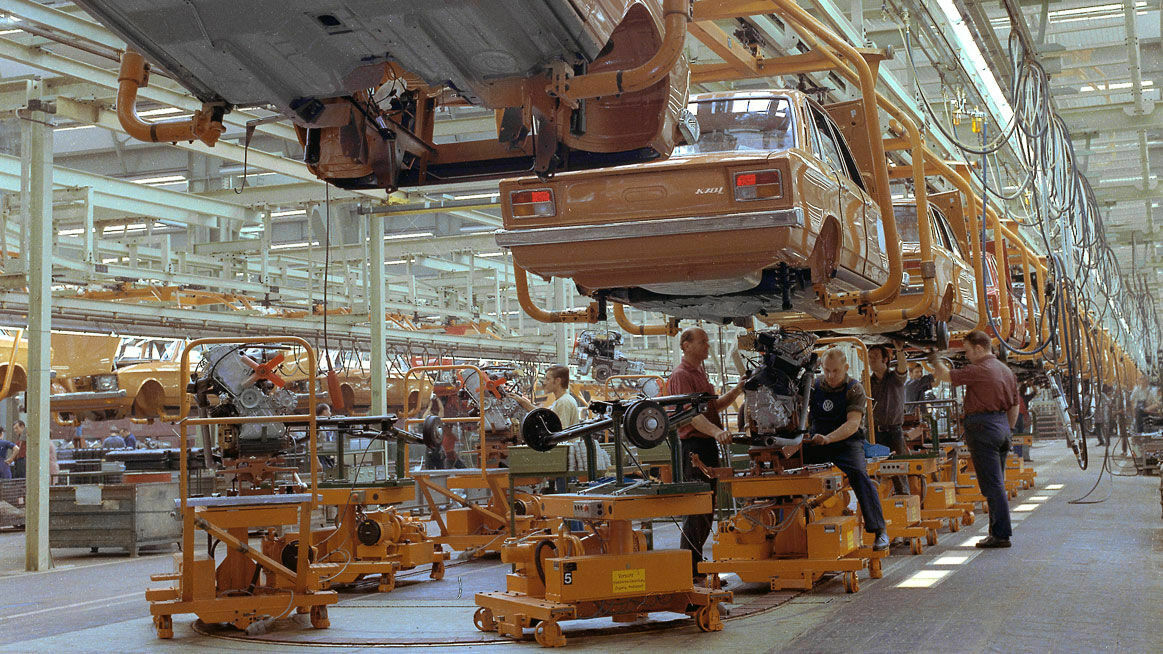

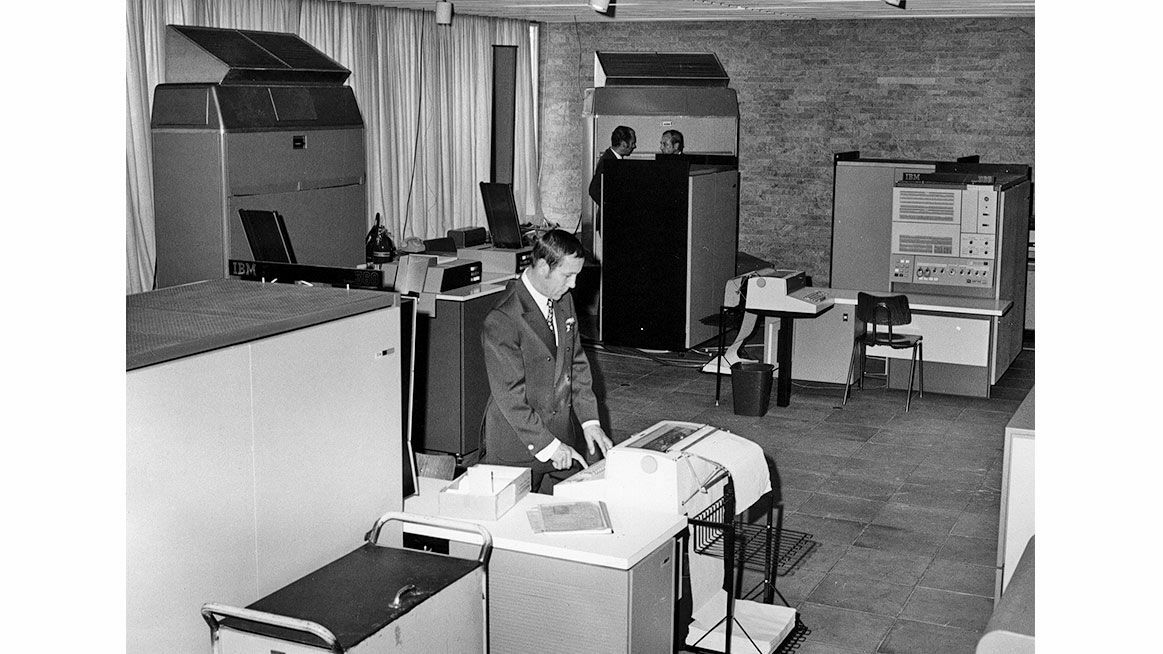

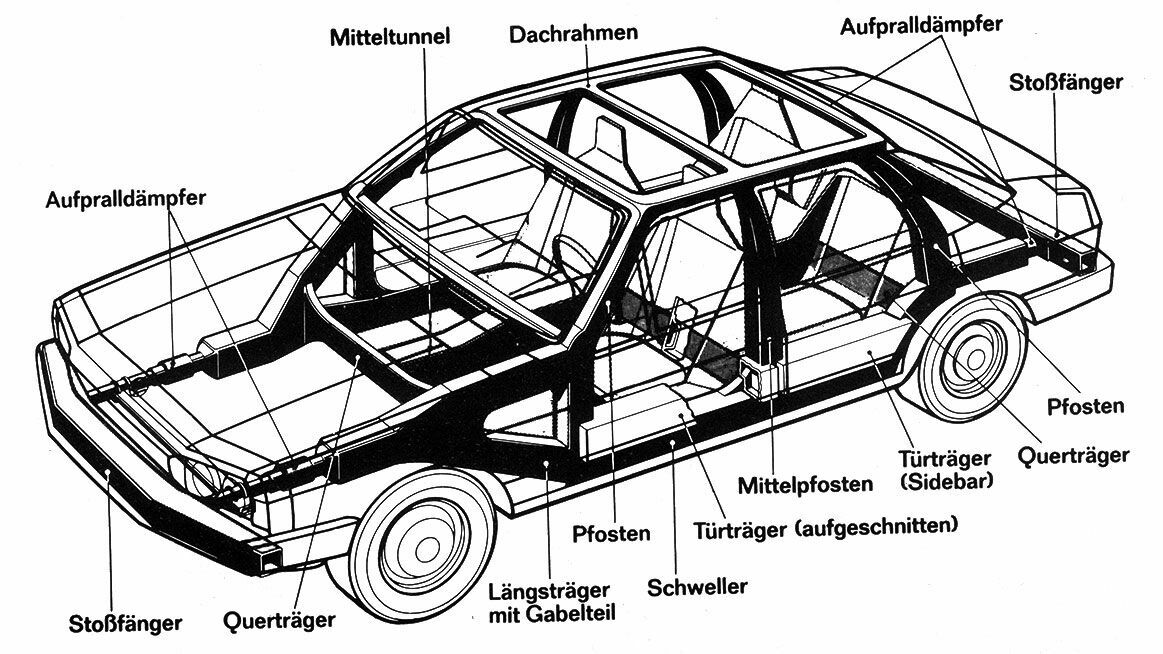

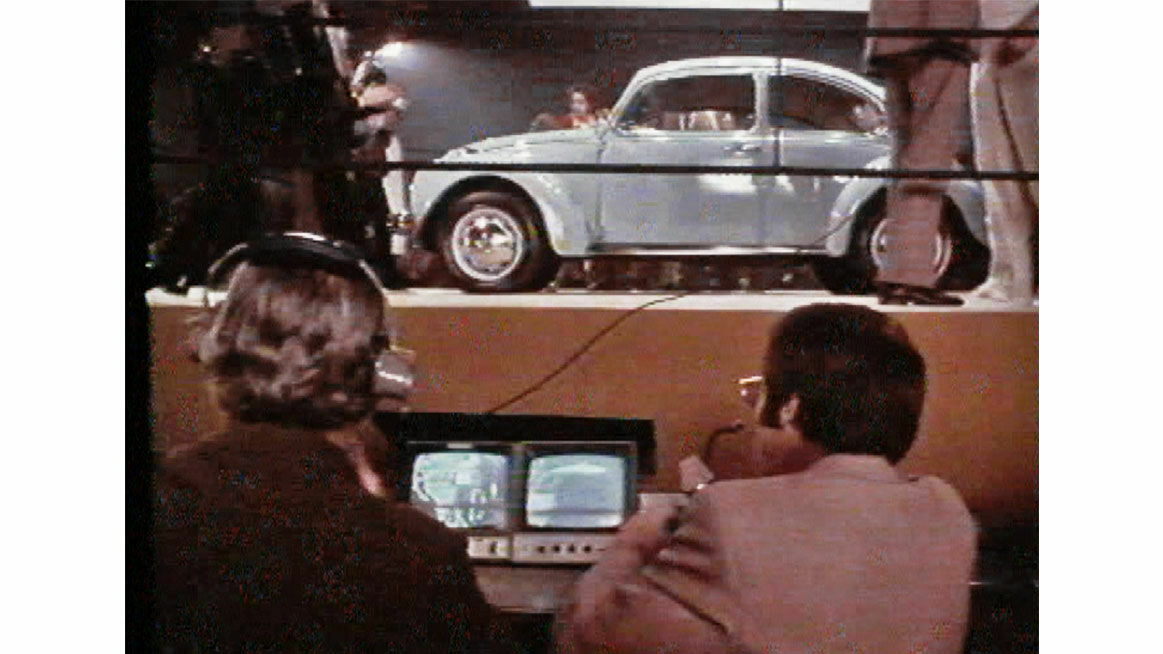

Volkswagenwerk AG confronted the emerging crisis with a combination of cost-cutting measures in all corporate divisions and heavy investment in the development of the new model range and the updating of production processes. At its core, the extensive rationalisation programme was aimed at introducing new technical and organisational systems in the production process, with computer technology delivering the key momentum for innovation. IT could now be used to manage production processes, greatly enhancing rationalisation there, as in the design function. Volkswagen had thus put all the essential elements of successful crisis management into place. All hopes now rested on the new generation of Volkswagens.