August 22

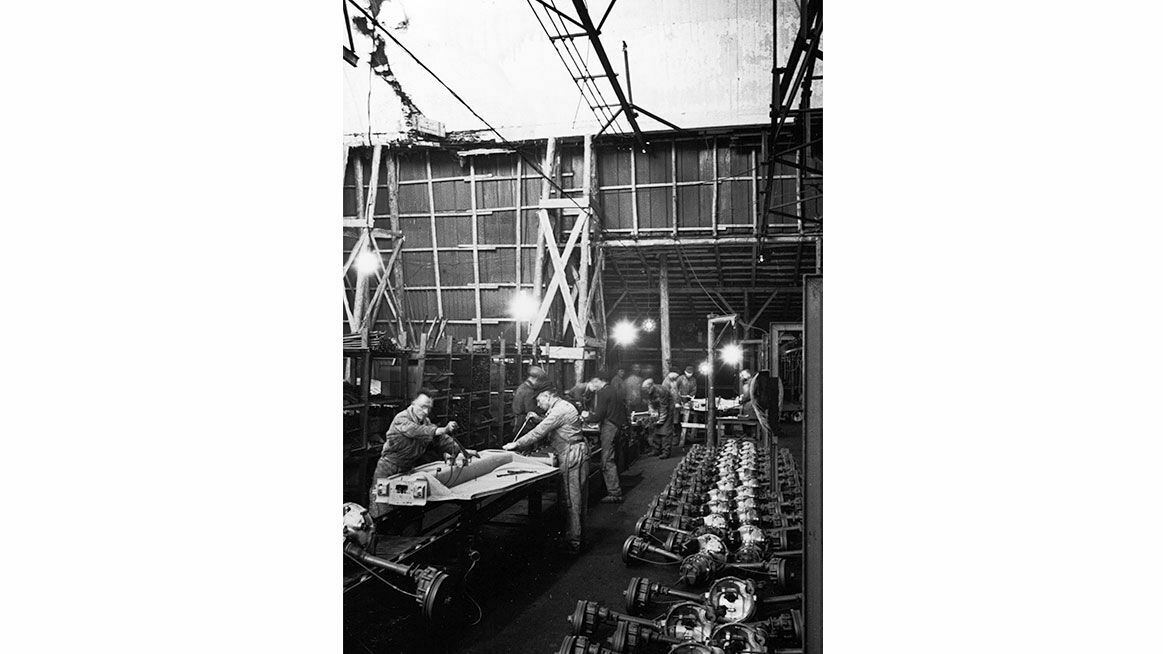

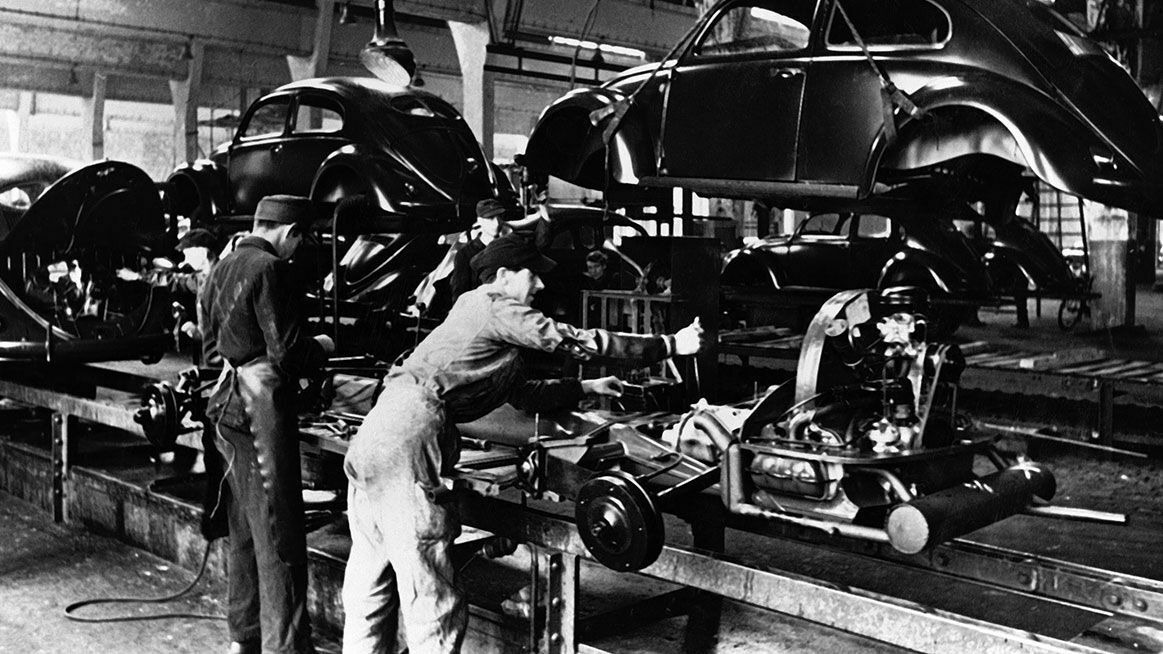

The occupation of the factory by American troops in April 1945 marked the beginning of the transition from armaments production to a civilian automotive concern, generating hope for a better future. As the largest and most important employer in a region with little industry, Volkswagen guaranteed the survival of the local population. The factory provided work, housing and food. These functions were certainly in the minds of the British Military Government when they took over the administration of the firm in trusteeship in June 1945. Their decision to reinstate peacetime production and the assembly line manufacturing of the Volkswagen saloon was primarily a decision made in their own interest. By assuming the responsibilities of an occupying force, their need for additional means of transport increased, especially since the war diminished the number of available British military vehicles. The production requirement for the occupation forces and British pragmatism saved Volkswagen from threatened dismantling.

Volkswagen’s position as a British-administered manufacturer proved advantageous in many ways. The Military Government provided the credit necessary for the resumption of production and was able to use its power of command to overcome many obstacles. Because the company manufactured goods for the Allies, it had priority in supply of raw materials that were then in short supply. The importance of this privilege during the time of economic control cannot be overestimated. Like most raw materials, the steel that was indispensable for car production was subject to a quota system.

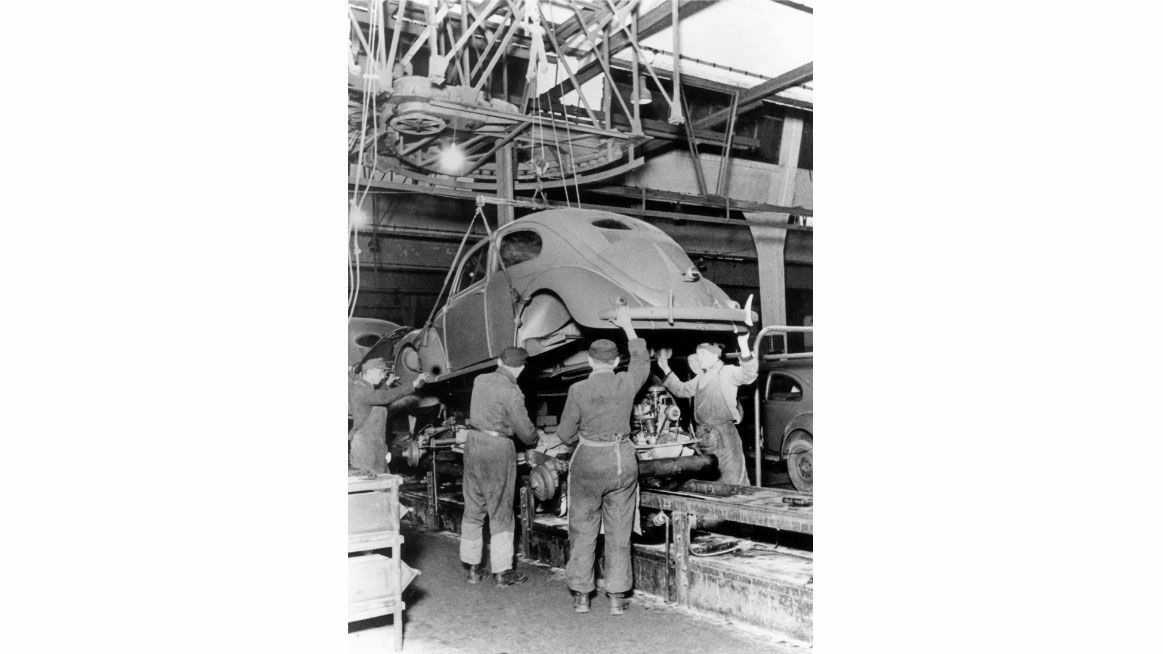

Volkswagen had an advantageous starting position when the peacetime assembly line was restarted. In spite of the damage inflicted on the factory buildings, the machine park, which was moved to dispersal sites, survived the Allied bombings largely untouched. If enough coal was available, the factory’s own power plant made it immune from the frequent power shutdowns of the post-war period. In addition, the company had its own press shop and the facility in Braunschweig compensated at least in part for the shortcomings of suppliers by producing its own parts and components.

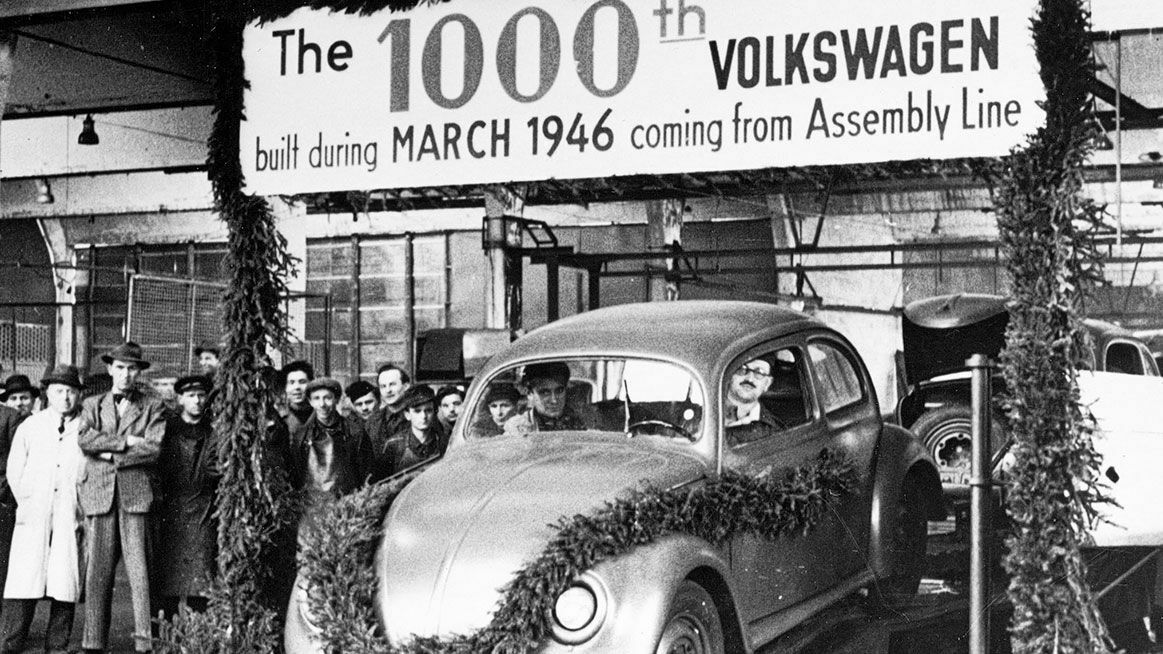

Despite British protection, the shortage of material and power seriously impaired production of the Volkswagen saloon after it was started on December 27, 1945. The steel that was allocated was often late and, because of a shortage of raw material, suppliers could not meet all of the company’s needs. The British Military Government had to quickly abandon their earlier plans of producing 4,000 cars a month for the occupation forces starting in January 1946. This initial calculated monthly production rate was finally reduced to 1,000 vehicles a month, a figure that remained stable until the currency reform and the introduction of the Deutschmark. In accordance with British orders, the German works managers tried to gradually increase car output to 2,500 a month, but these attempts were thwarted by the shortage of raw material and difficulties in procuring parts. The malnutrition and general exhaustion of the workforce were further problems. Because workers needed to forage for food and to purchase goods on the black market in order to assure survival, there was also chronic absenteeism. For the first two years after the war ended it was therefore imperative to provide the employees with food and clothing. This responsibility was gradually handed over to the Works Council, and it took up most of their time.

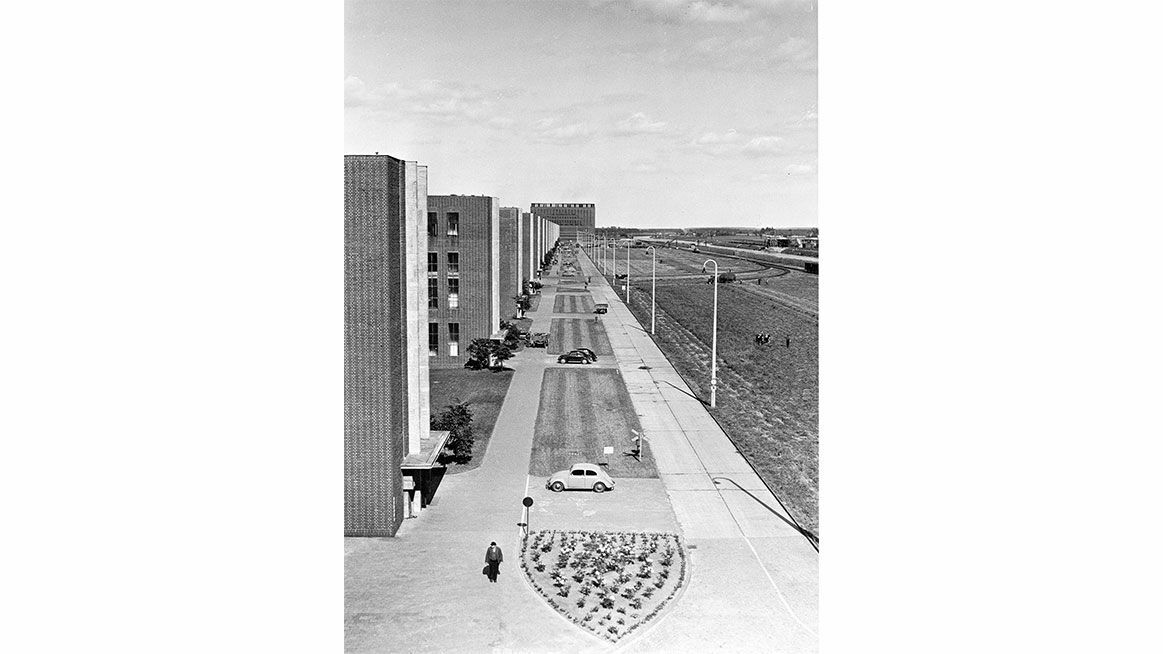

Plans to expand production were also hindered by a shortage of workers. A shortage of housing and high employee fluctuation made it more difficult to recruit a permanent workforce. For many of the refugees and migrants coming to Wolfsburg by the thousands from the former German territories in Eastern Europe in search of food and housing, a job at the Volkswagen plant was only an intermediate stop on their way to West Germany. The chronic housing shortage in Wolfsburg caused many of the workers to simply move on. For most of the plant workers, living conditions were basic at best. Separated from their families, they lived in the sparsely decorated camp barracks where the forced labourers had earlier been housed. Desperately needed skilled workers as well as managerial staff could hardly be enticed to stay or be convinced to come to work for the company under these conditions. Because the construction of new housing was hardly a realistic prospect during these first post-war years, the company was forced to renovate and expand the existing barracks. The housing problem was eased a little in this way, but not solved. Only when the surrounding region was linked to the factory site by bus and train, and with the construction of company-owned apartment buildings beginning after 1950, did it become possible to build up a core workforce.

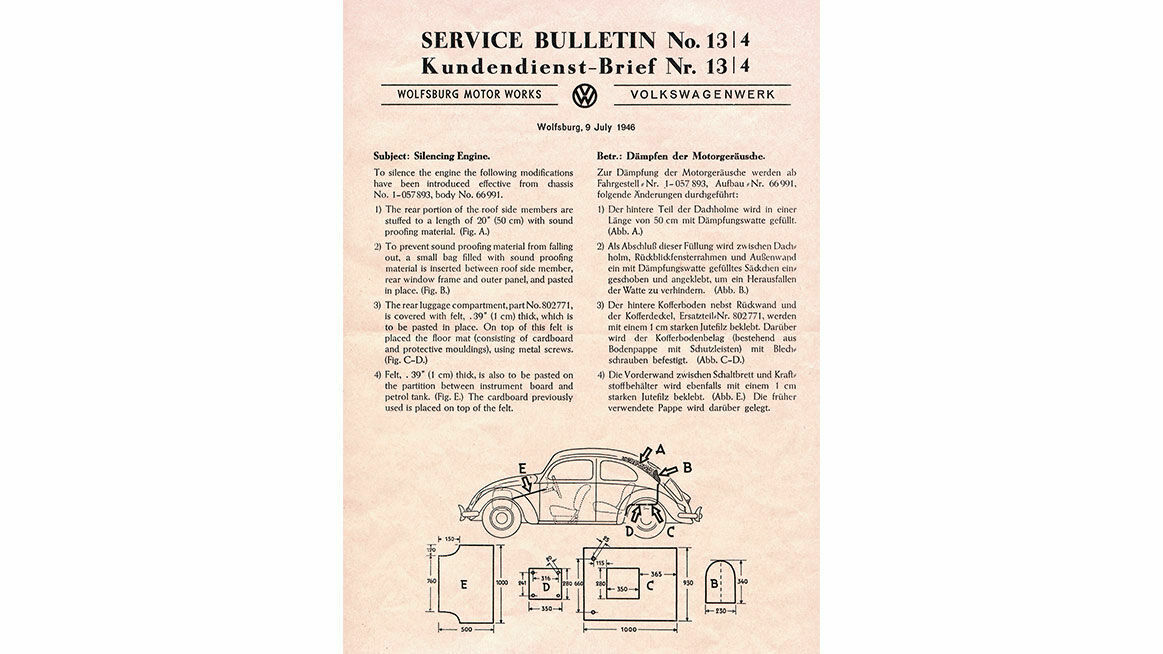

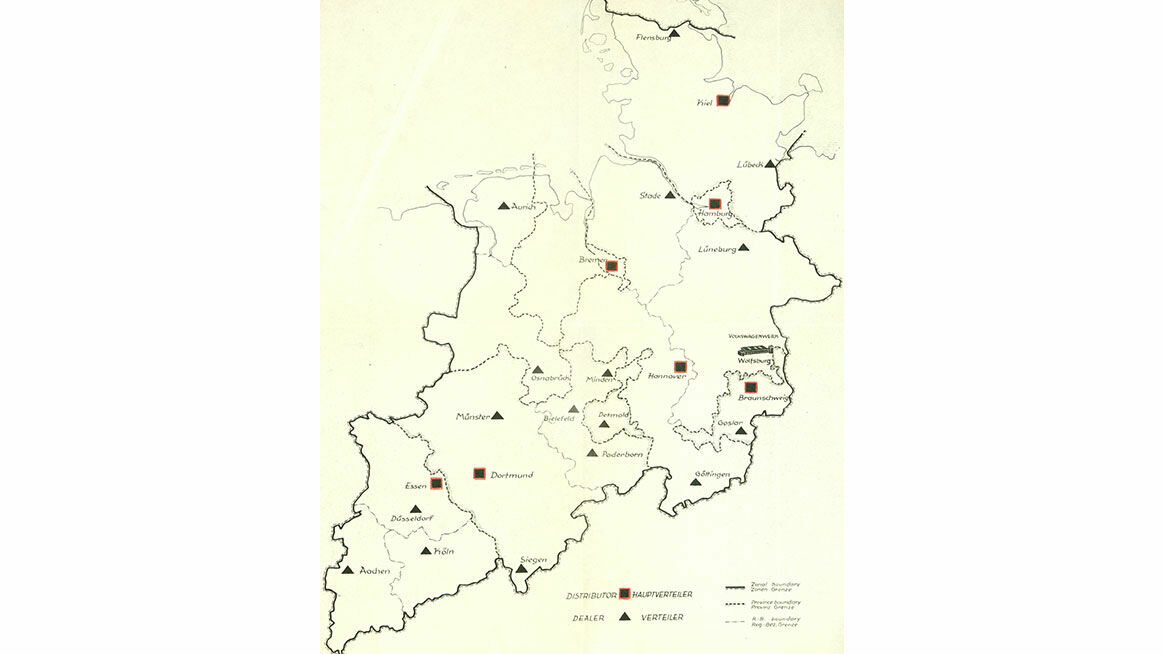

The British trustees established key conditions for the company’s future success by eliminating disadvantages the firm had compared to its competitors. First of all, at the end of the war Volkswagen had only the beginnings of a service and distribution system. The German Labour Front (DAF) had been intended to set up both, but Hitler’s grandiose plans for mass motorisation were shelved when preparations for war began. In accordance with British initiatives, a service function was set up by the end of 1945. This comprised a parts warehouse, a technical department and a service training school. Starting in February 1946, dealers and mechanics from authorised workshops received training there. Volkswagen assisted the repair workshops by providing service bulletins and repair manuals. In addition, a damage file index was set up which gave the technical department a systematic method of dealing with problems for the first time. The service department acquired an excellent reputation within only a few years and profited greatly from the experience of the Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers, who set up their own workshop in the Volkswagen plant. The organisation of a sales network progressed just as swiftly after the prospect of selling Volkswagens to the general public was proposed in the production programme issued in June 1946. Factory management pressed for the establishment of a dealer network, and the British agreed to this proposal for their zone in October 1946. It was to be supported by two field representatives and subjected to strict quality controls. The exchange of experience between dealers and management developed in time into a trusted partnership, which was to become profitable for both sides.

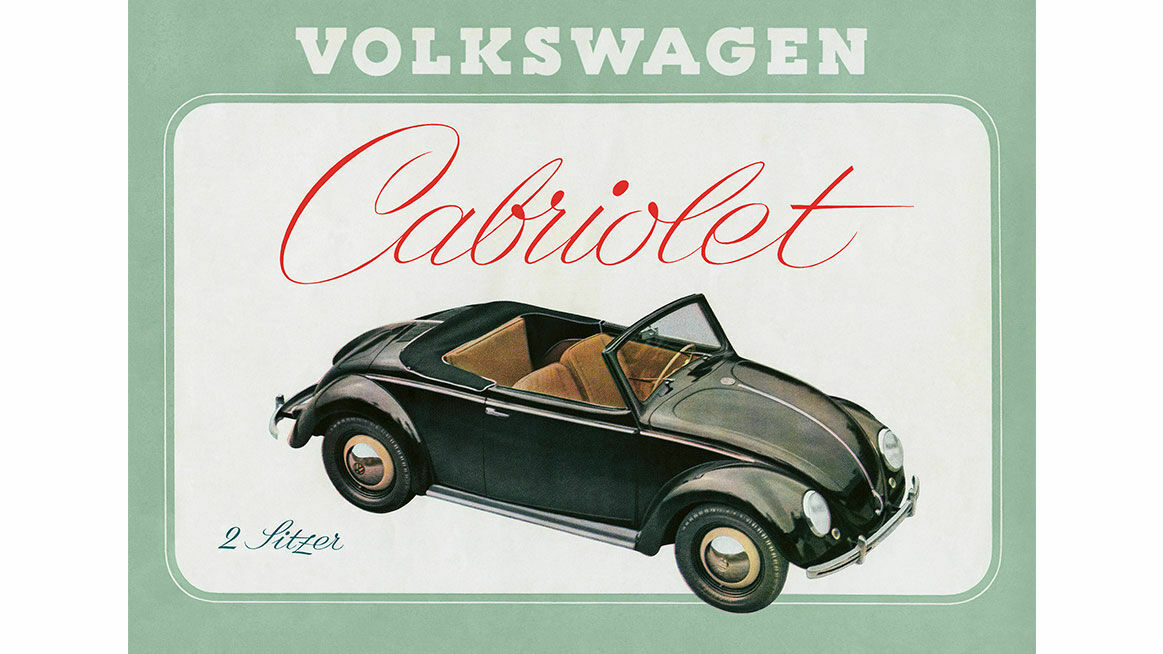

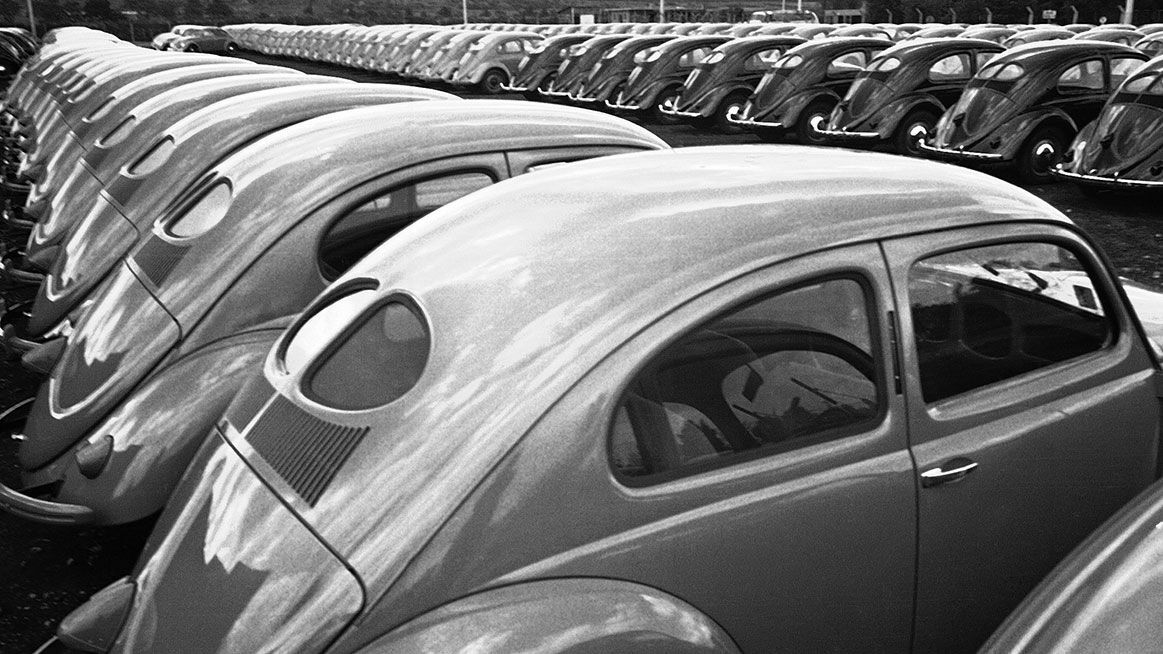

The British introduced a second decisive development in the summer of 1947, with long-term effects. Their decision to export Volkswagens was aimed at replenishing the currency reserves of a British economy still reeling from the financial costs of the war, but it also laid the foundation for the international success of the Volkswagen saloon and the company’s launch onto the global marketplace. The start of exports came at an unfavourable time, however. The supply crisis became so severe that the number of vehicles that the plant was to produce could not be met in August and November 1947. It was only the following year that foreign business gradually took hold.

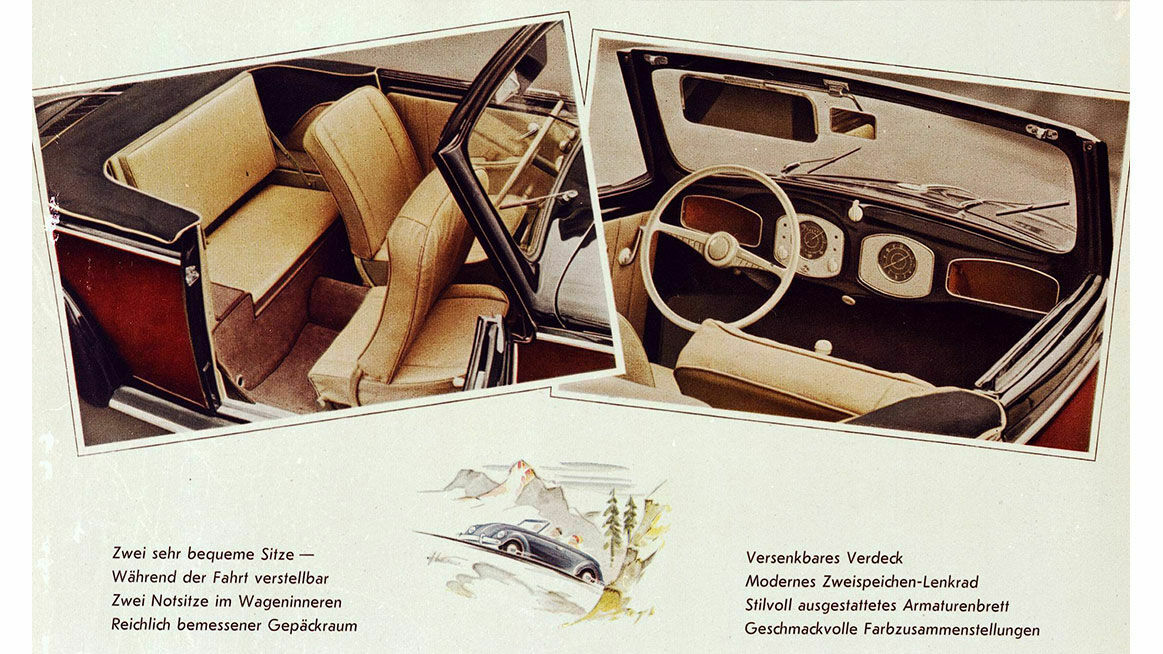

In the meantime, the factory management had developed a saloon model whose workmanship and features were superior to the standard domestic version, making it suitable for export. Thanks to high-quality paintwork in attractive colours, comfortable upholstery, chrome bumpers and hub caps, Volkswagen was able to gain a competitive edge over foreign manufacturers. In 1948, 4,385 vehicles were exported to European countries: 1,820 to the Netherlands, 1,380 to Switzerland, 1,050 to Belgium, 75 to Luxembourg, 55 to Sweden and 5 to Denmark. Exports the following year climbed to a total of 7,127 vehicles, meaning that Volkswagen sold over 15 percent of its total production to European markets.

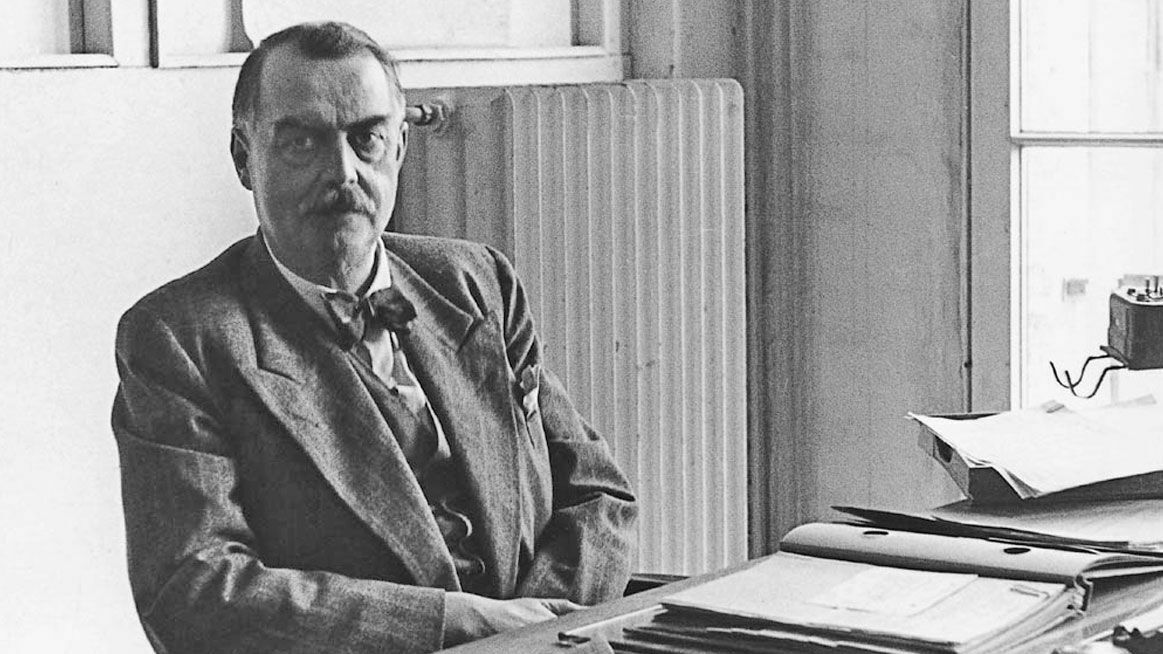

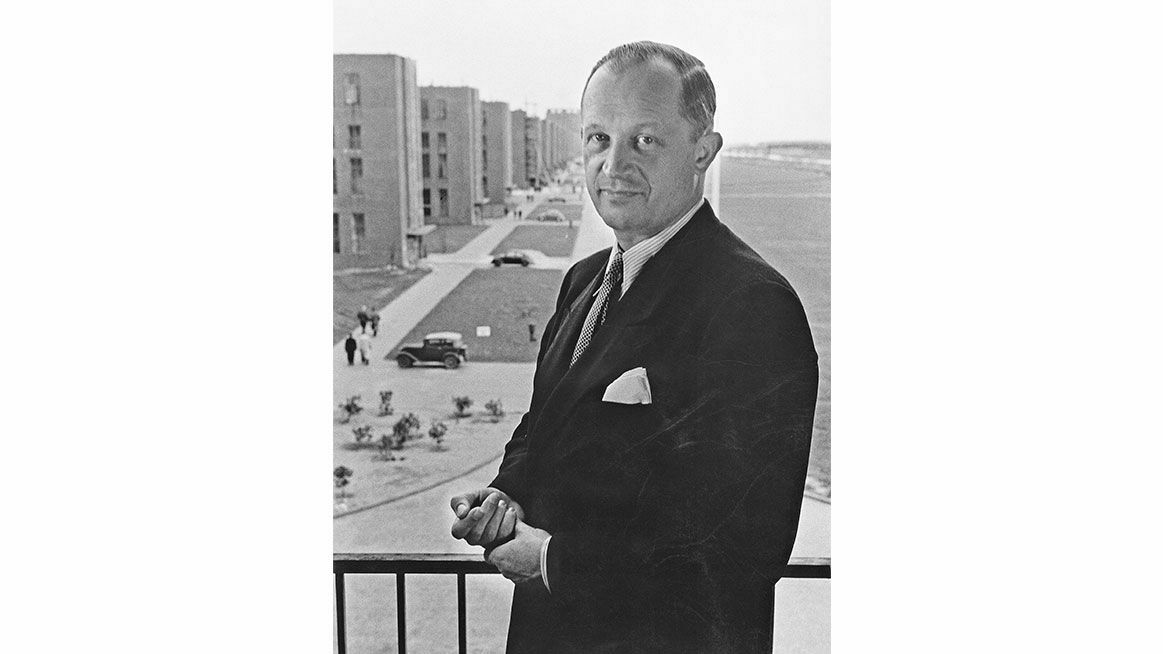

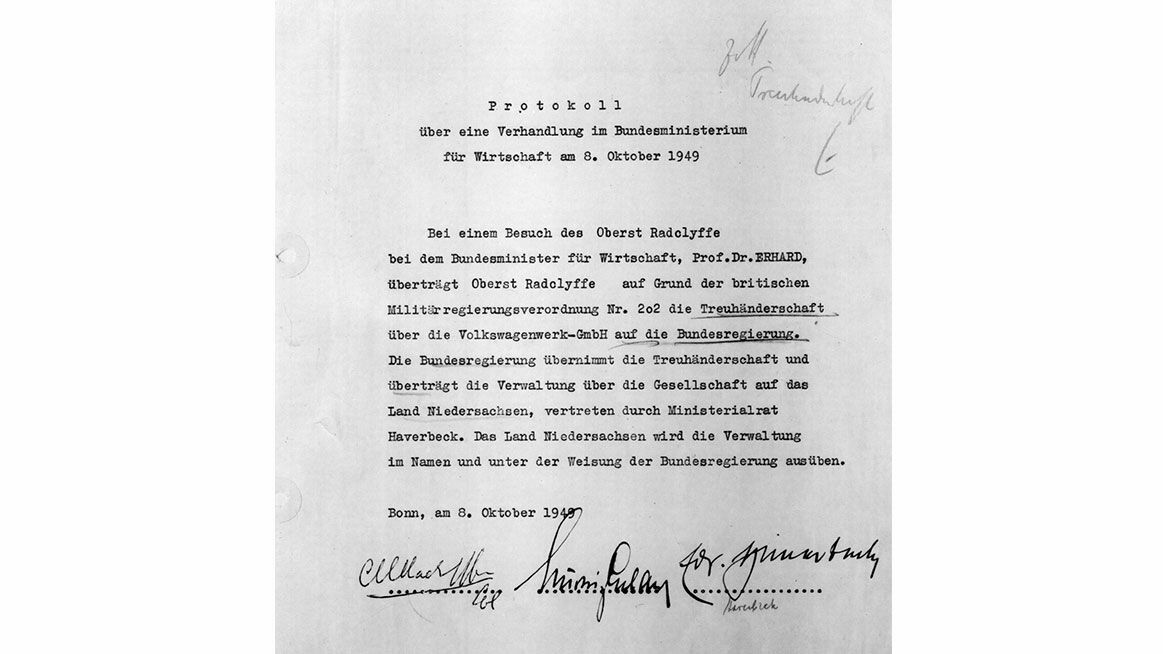

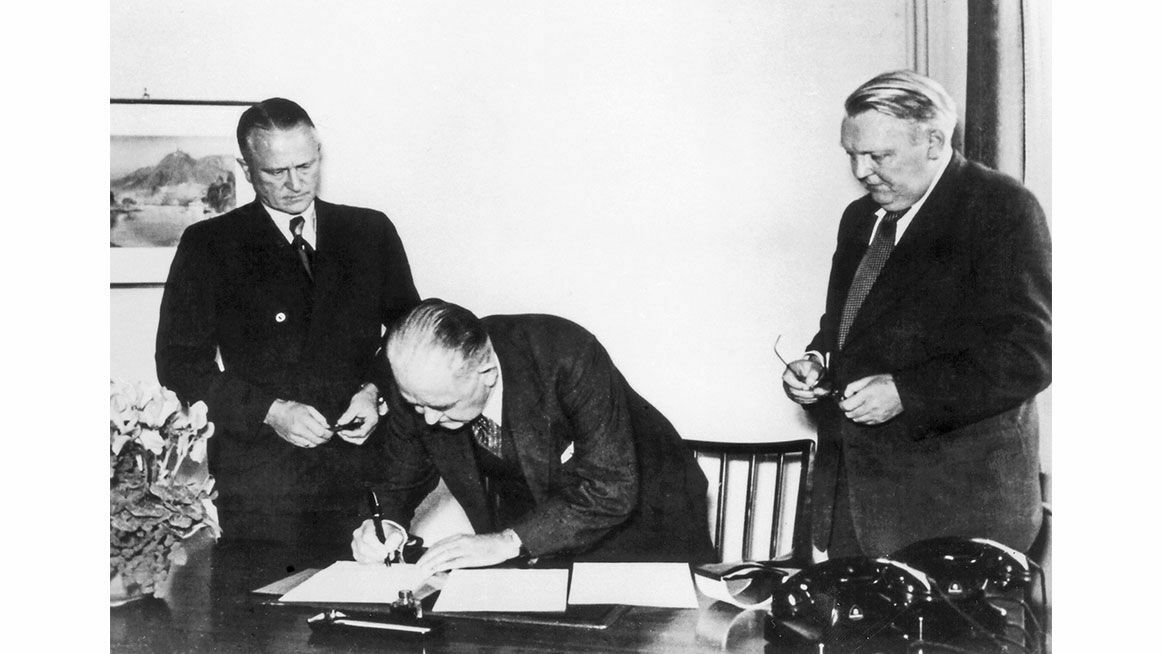

The British Senior Resident Officer, Major Ivan Hirst, played a decisive role in the conversion of the armaments factory into a car company. Thanks to his improvisational talents, technical and organisational problems were solved and supply shortages overcome. Hirst steadfastly pressed for improvements in the quality of the saloon, and this was to become an important factor in Volkswagen’s international reputation. When the British Military Government turned over the trusteeship of Volkswagenwerk GmbH to the German Federal Government and its administration to the State of Lower Saxony on October 8, 1949, the company was in good condition. It had approximately 10,000 employees, a monthly production output of 4,000 vehicles and cash reserves of about 30 million Deutschmarks. Production for the occupation forces gave Volkswagen a substantial advantage over the competition. In 1948/49, it built just under half of all the cars produced in West Germany. The firm was well ahead of other car-makers in the export business too. Volkswagen was in a strong position when it joined the international competition for customers and market share.