August

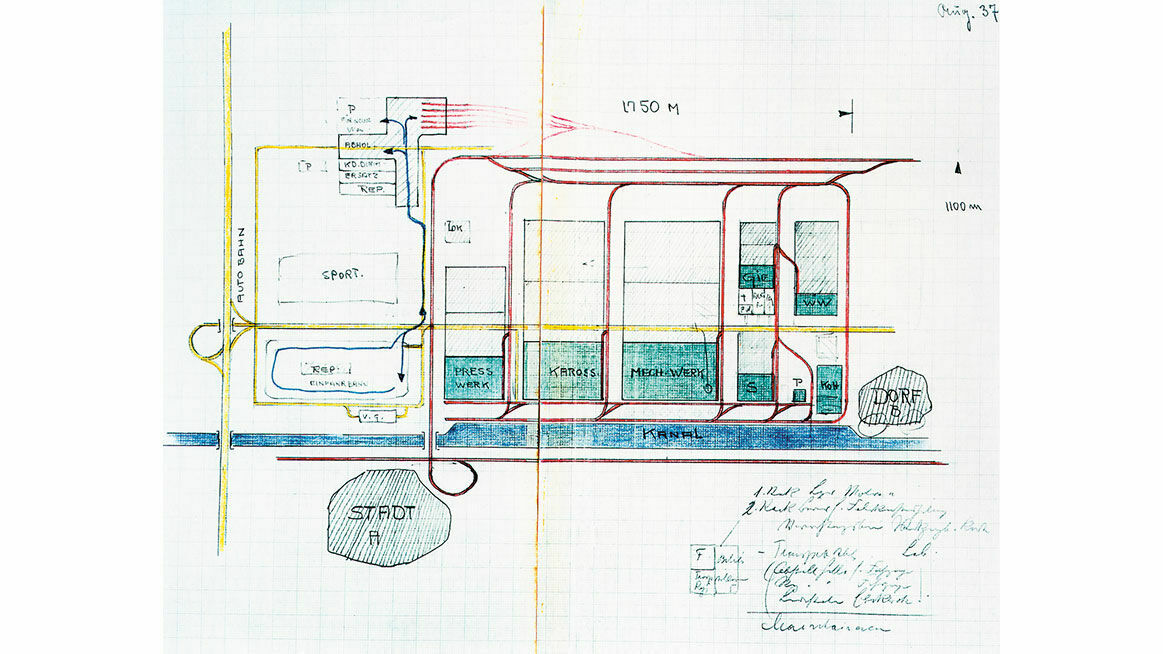

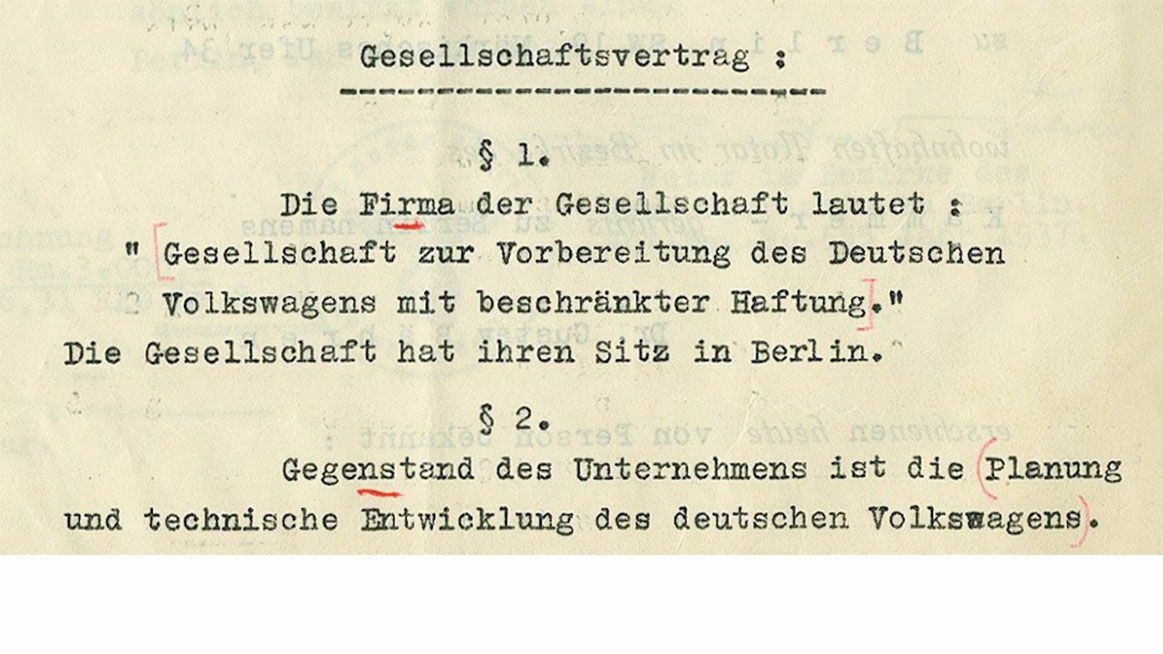

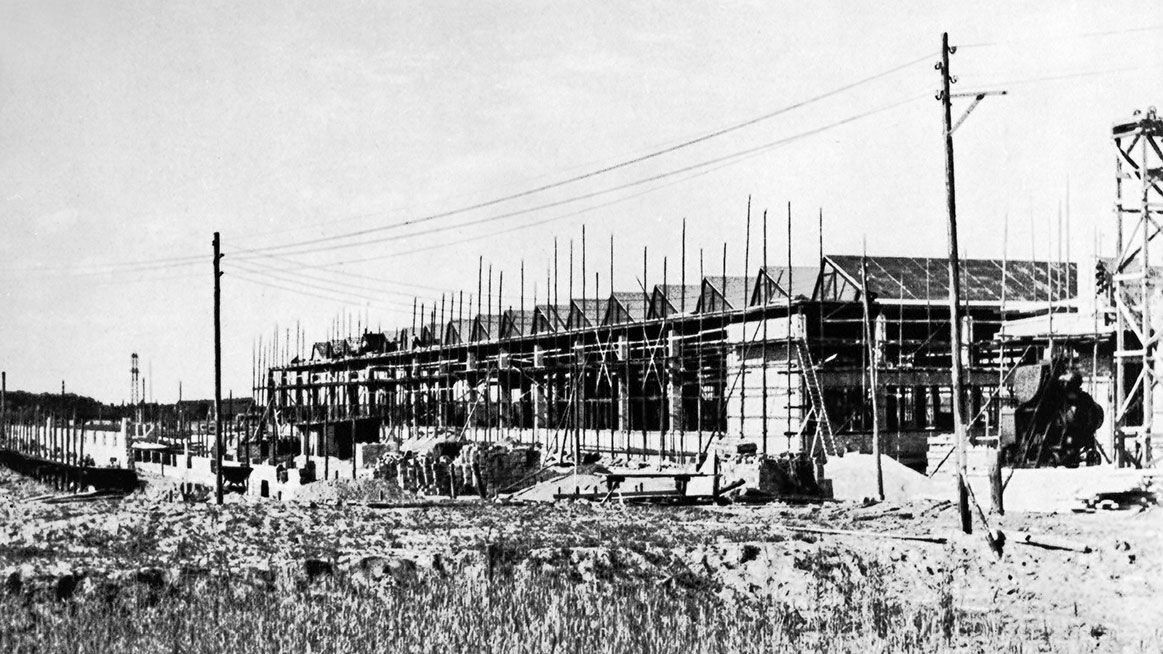

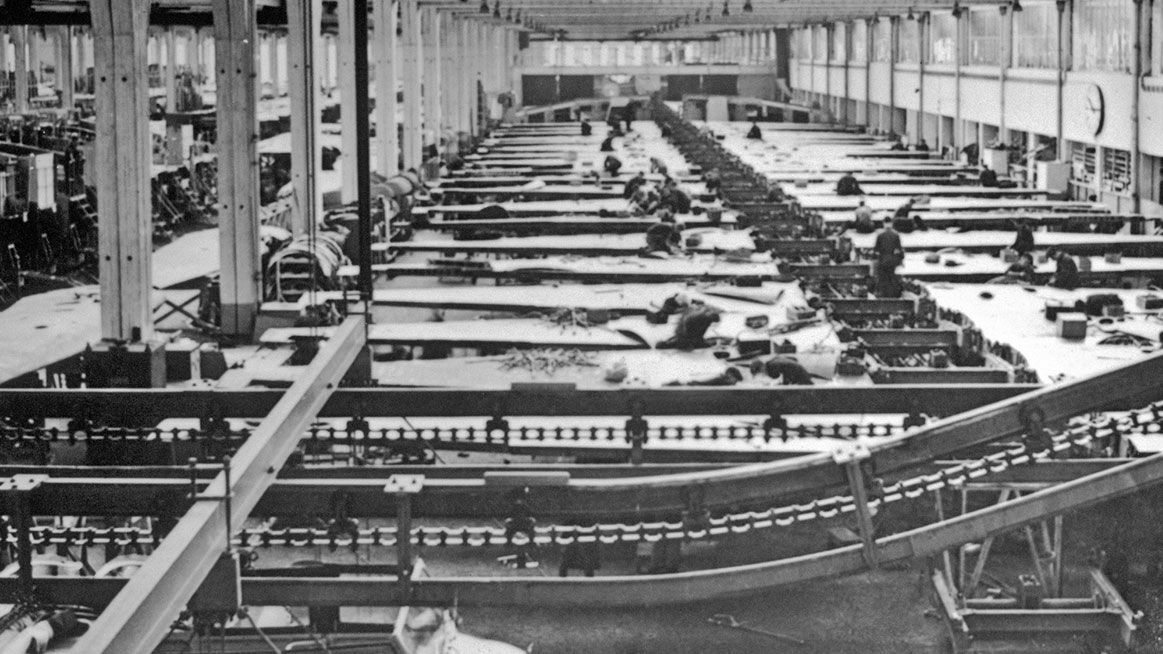

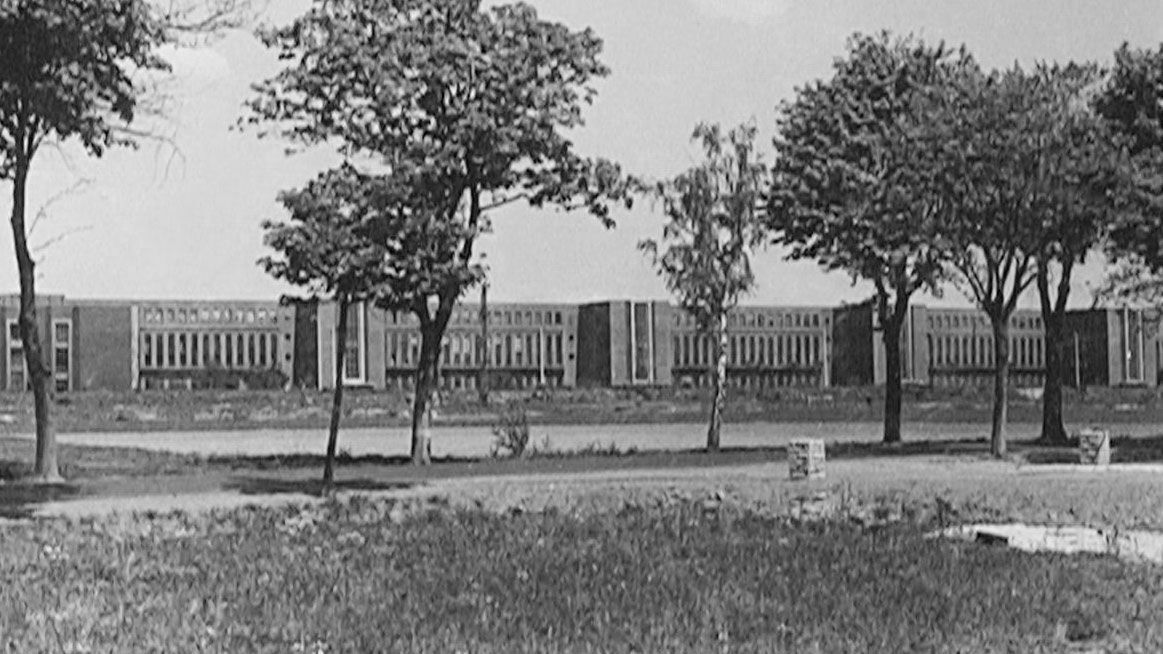

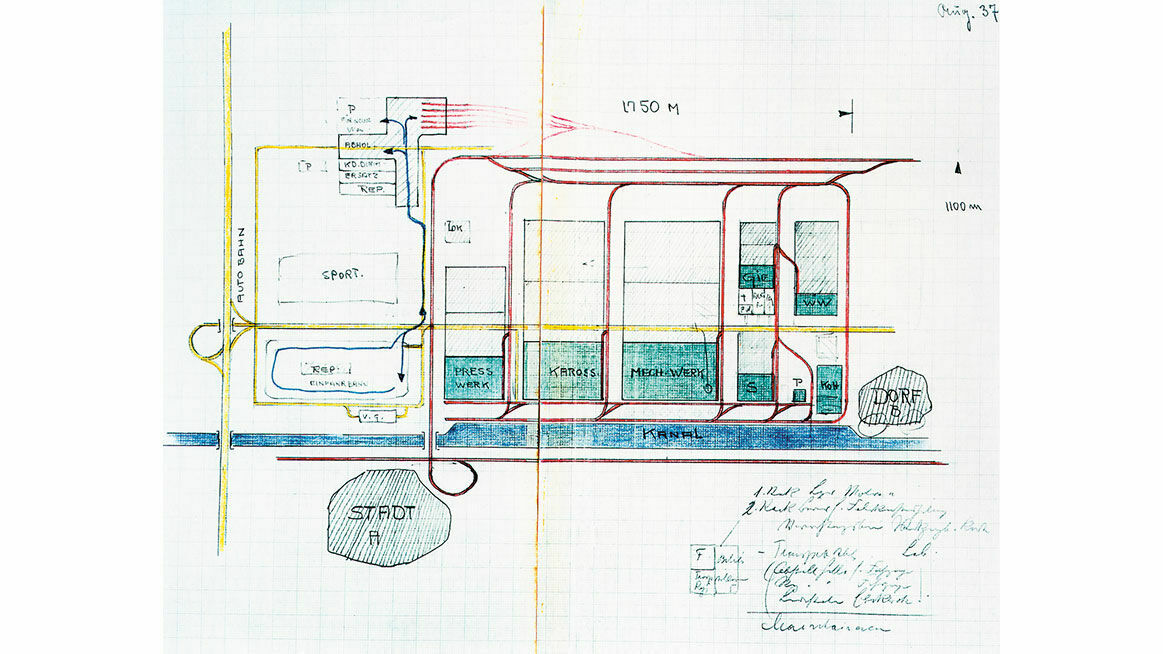

This impasse was broken in January 1937, as responsibility for the project was assumed by the Deutsche Arbeitsfront (DAF), or German Labour Front, a unified organisation encompassing both employers and employees, which was looking for a prestige project to polish up its image. In the same period, in early April 1937, testing of the 30-vehicle W30 series began, involving more than two million kilometres of trials in total. On May 28, 1937, the DAF in Berlin established the “Gesellschaft zur Vorbereitung des Deutschen Volkswagens”, or “Corporation to prepare the way for the German People’s Car”, which on September 16, 1938 was renamed Volkswagenwerk GmbH. In February 1938 work began on a site east of Fallersleben on the Mittelland canal to construct the main plant, which was designed to operate as a vertically structured and largely autonomous model factory. The target was to produce 150,000 units in the first year after the plant’s scheduled opening in Autumn 1939, and 300,000 in the second year, with capacity increasing to 450,000 units by the year after. The medium-term target was to build 1.5 million “People’s Cars”. The workforce was planned to grow from 7,500, to 14,500, and ultimately to 21,000 people. There was no financing for the estimated investment of some 172 million Reichsmarks in the site and 76 million Reichsmarks for the machine plant. Revenues from the sale of property confiscated from the now disbanded independent trade unions were earmarked to help pay for the investment.

The size, technical equipment and manufacturing depth of the facility were oriented to that of Ford’s River Rouge plant in Detroit, which was considered the most advanced car factory in the world and was visited twice by Ferdinand Porsche and the planning team. In parallel with the construction of the main plant in what is today Wolfsburg, a facility was built in Braunschweig (Brunswick), known as the “Vorwerk” (outworks), to provide tools and dies and to serve as a training centre for the skilled workforce required. Shortages of labour and raw materials delayed the progress of both construction projects.

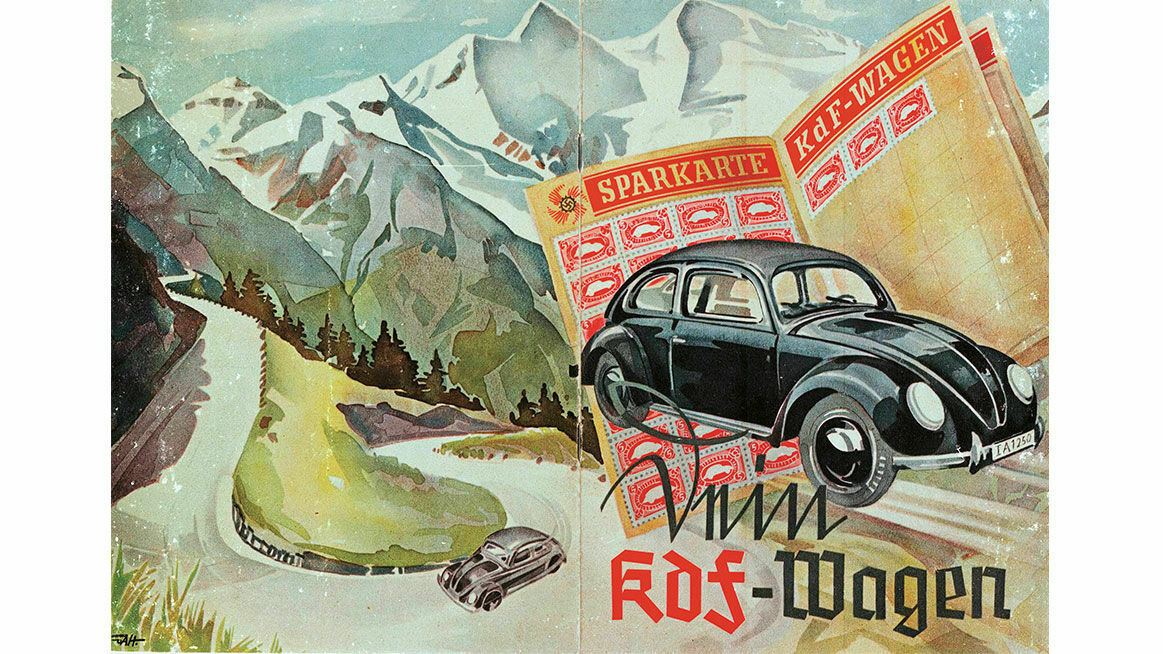

At the propaganda-laden foundation-laying ceremony on May 26, 1938, Hitler christened Ferdinand Porsche’s vehicle the “KdF-Wagen” (based on the Nazi slogan “Kraft durch Freude”, or Strength through Joy). Accompanied by a massive advertising campaign, on August 1, 1938 the DAF launched an instalment savings scheme for buyers of the KdF-Wagen. The car could be acquired through a minimum payment of just five Reichsmarks a week to the DAF. But the ambitious plans were thwarted by lack of buying power – a Volkswagen was still realistically unaffordable for an industrial worker. Some 336,000 people ultimately signed up to the instalment savings scheme – far fewer than the target envisioned by the gigantic manufacturing plan.

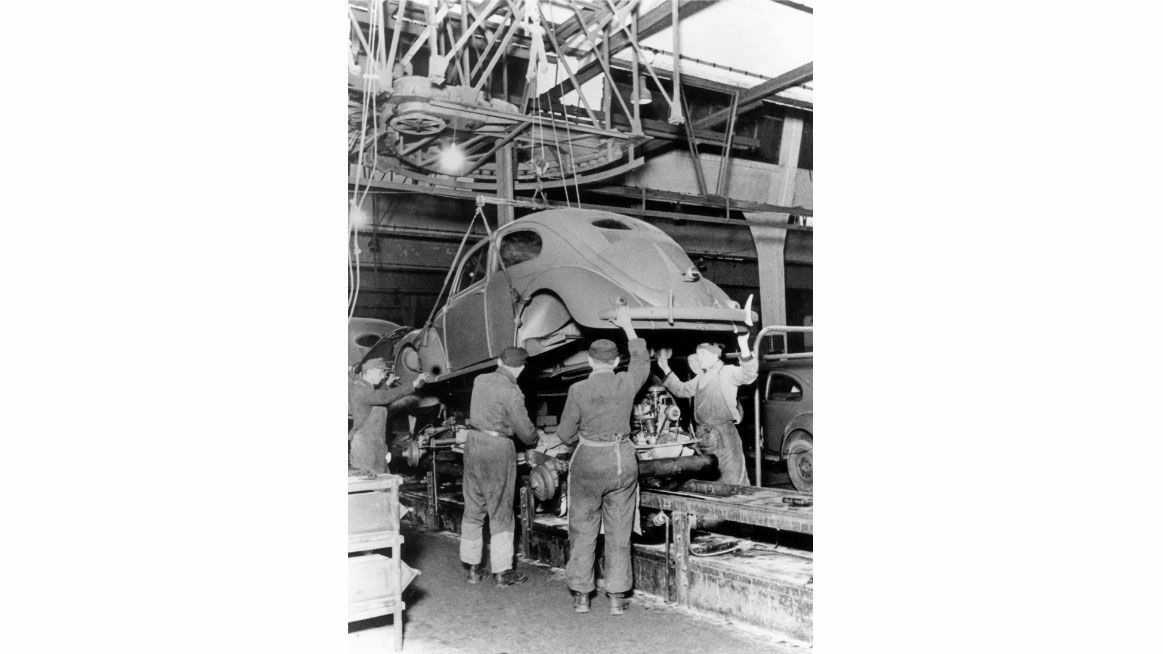

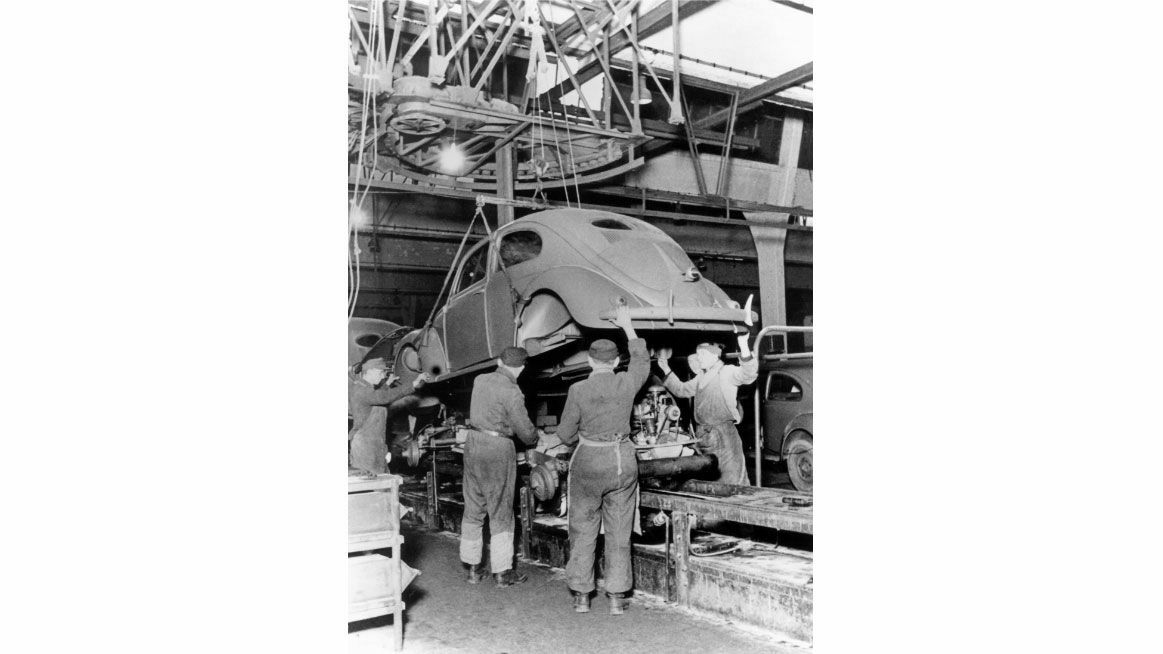

While the Vorwerk did in fact begin training apprentices and making tools and dies in 1938, fitting-out of the main plant was continually postponed as priority was given to armaments. Not a single car had been produced by the time the war began on September 1, 1939. Instead, the retooling of the plant for armaments production meant that the company’s entire operations were re-aligned. In late 1939, Volkswagenwerk GmbH began carrying out repairs for the German Air Force on the Junkers Ju 88 combat aircraft, as well as supplying wings and wooden drop tanks. As the Army became more motorised in 1940, the company started making cars. Mass production of military utility vehicles (Kübelwagen), and then from 1942 amphibious personnel carriers, established a second arm of the business. By the end of the war the plant had built a total of 66,285 vehicles. Between 1940 and 1944 sales turnover rose from 31 to 297 million Reichsmarks.

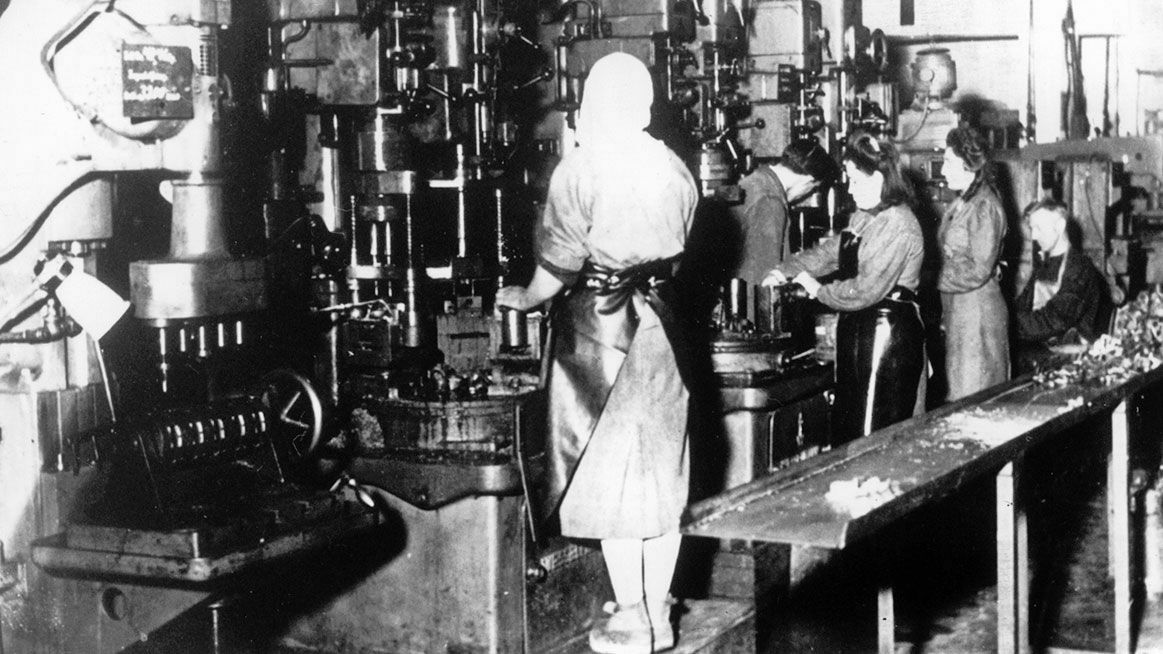

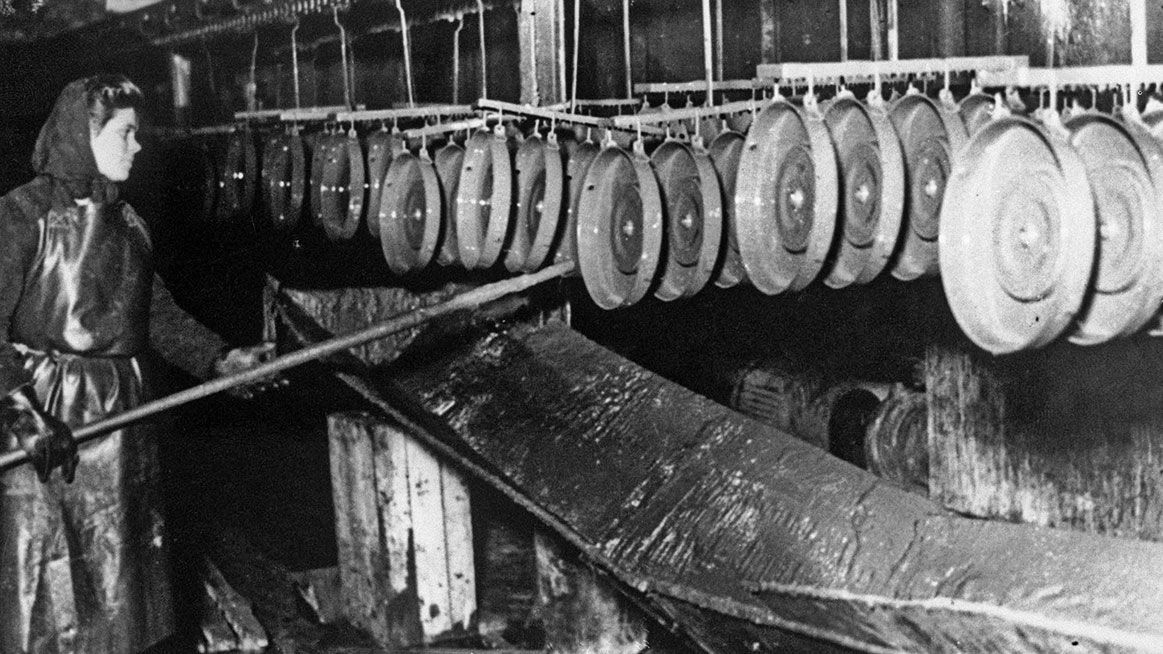

The company’s involvement in the German armaments industry led to the acquisition of subsidiaries, including in Luckenwalde and Ustron, from 1941 onwards. In 1943/44, Volkswagenwerk GmbH expanded its production capacity by outsourcing to France and by repurposing iron ore and asphalt drift mines to create underground manufacturing facilities. Following a number of bombing raids on the complex on the Mittelland canal, in 1944/45 the business was increasingly decentralised as production departments were relocated to temporary premises. The productivity needs of the growing armaments operation were met from Summer 1940 onwards by the increasing use of forced labour. The first group of such slave labourers were Polish women deployed at the company’s main plant. Later, prisoners of war and concentration camp inmates were assigned to work there – an estimated 20,000 people in total. They came from European countries which had been occupied by, or were under the control of, the German Reich, and in 1944 accounted for two thirds of the company’s workforce. In Nazi Germany forced labourers had no rights, and were subjected to varying levels of racial discrimination. Insufficient food, physical violence and exploitation undermined their health and endangered their lives.

The US troops who arrived on April 11, 1945 stopped the plant’s armaments production and liberated its slave workforce. The longed-for end of the Nazi dictatorship marked the beginning of a new era for Volkswagen too.