“Der Motorwagen”

In the early 20th century the motor car was still a rare mode of transport. There were barely 16,000 throughout all of Germany in 1910. Some were driven as a form of adventure sport, while others were considered a mark of prestige. Cars remained the preserve of the rich and the beautiful people: Hand-crafted models from Benz, Daimler and Glaser were owned by Kaiser Wilhelm II, as well as by steel magnates and bankers. A large number of makes were serving a very small luxury market.

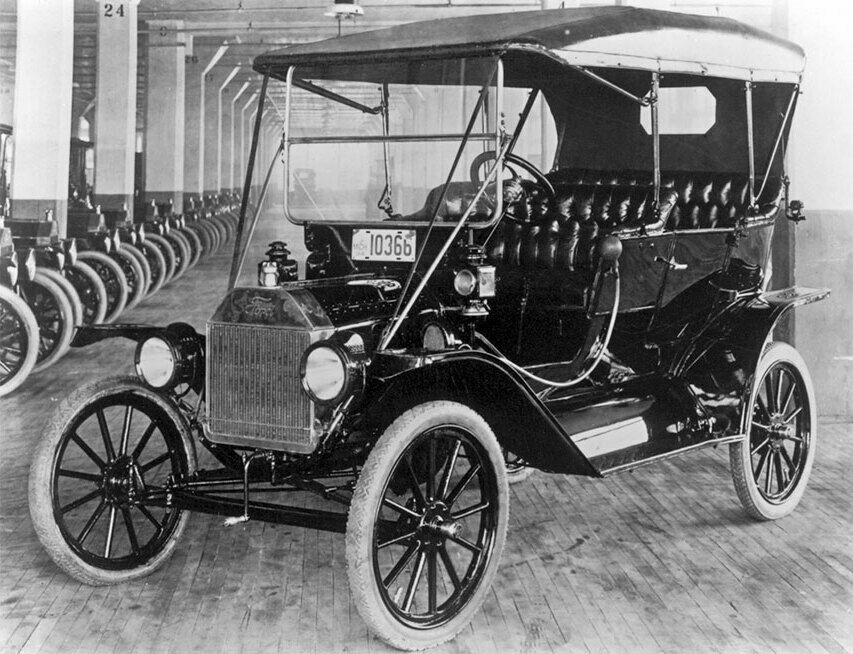

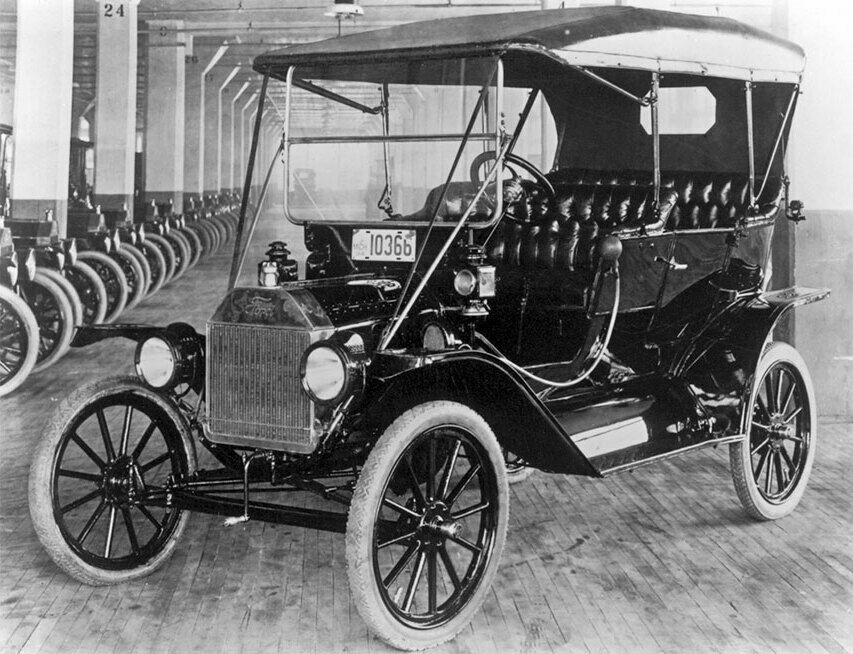

Yet as early as December 1904, writing in the Viennese journal “Der Motorwagen”, Aachen-based engineer Heinrich Dechamps was asking whether the motorcycle would maintain its popularity, or whether in fact a different kind of vehicle would be capable of assuming the mantle of personalised transportation for the masses: the “Volksautomobil”, or People’s Automobile. The dream of personal auto-mobility was extending into new segments of the population. The mass market for cars emerging in the USA was the principal driver of progress. The Ford Motor Company began making its robust new Model T in 1908. It sold initially for $ 825. By 1920, thanks to assembly line technology and mass production, its price had fallen to $ 450, allowing whole new social groups to become car-owners. Within a decade, the USA had become a truly automotive society. In Germany too, where before the First World War auto-mobility had been the preserve of social elites keen to enjoy the new feeling of power and speed, attention likewise began to turn to the production of small cars. The two-seater “Doktorwagen” launched by Opel in 1909 at a price of 3,950 Marks proved popular due to its manoeuvrability and easiness to drive, and sold at a respectable rate of just under 800 units a year. In 1912 the company named it the “Volksautomobil”, or People’s Automobile. In 1913, car-maker Wanderer in Chemnitz launched its two-seater Type W 3. Though well received, it failed to sell in significant numbers. Any further advances were interrupted by the First World War.

In 1919, Citroën opened a new factory operating conveyor belts in France with capacity to produce 100 cars a day. In Germany, however, the automobile remained a luxury item. That situation did not change fundamentally even with the launch of mass production by Opel in Rüsselsheim and Hanomag in Hanover from 1924/25 onwards. The country was lagging far behind France and the UK – and certainly the USA – in terms of car ownership. Nevertheless – thanks in part to their low price of 2,950 and 1,995 Reichsmarks respectively – the small cars sold by Opel and Hanomag were already being labelled “People’s Cars” (“Volkswagen”).

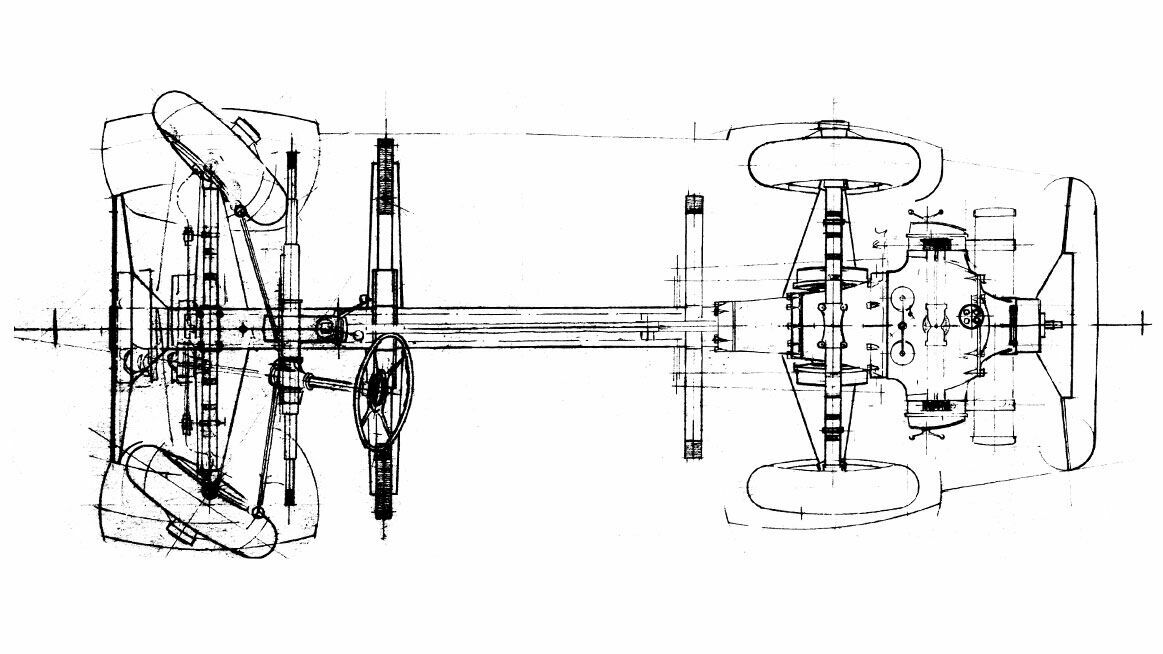

The idea of making a car for a mass market encouraged designers to come up with technical innovations. In 1925, an 18-year-old Hungarian technical academy student named Béla Barényi – who was later to make a name for himself through his improvements to vehicle safety – drew up a “chassis design for a People’s Car”, featuring a rear-mounted boxer engine and with its gearbox located in front of the rear axle. Another Hungarian, motoring journalist and designer Josef Ganz, had been promoting the idea of a “People’s Car” since the mid-1920s, and brought out a number of prototypes for ultra-compact cars based on a combination design. Engineer Hans Ledwinka, born in Klosterneuburg near Vienna but working in the Czech town of Nesselsdorf, developed the Tatra 11, which for the first time featured a central tubular frame, a pendulum axle and an air-cooled two-cylinder boxer engine.

Ferdinand Porsche likewise took an early interest in small cars. His “Sascha” lightweight car designed at Steyr in 1922, featuring a 1.1 litre capacity four-cylinder engine developing 45 horsepower, did not go into production. In 1931, having set up as a freelance designer in Stuttgart, Porsche developed what he called a “quality small car for everyone” on behalf of motorcycle manufacturer Zündapp. The two-door model, designated internally by Porsche as the Type 12, had four seats. The Type 32, designed in 1933 for the NSU Vereinigte Fahrzeugwerke car company, featured torsion bar suspension and a rear-mounted air-cooled four-cylinder boxer engine. In the midst of the global financial crisis, concerns about high manufacturing and capital investment costs prevented the two bike-builders from moving into automobile production.

The search for suitable technical solutions for small cars was well underway by the early 1930s. But public interest in a low-cost “People’s Car” was not yet enough to bring down the high cost of ownership, which still impeded mass car sales. Adolf Hitler’s announcement of government funding for motorisation and backing of the automotive industry at the International Automobile and Motorcycle Exhibition in Berlin soon after assuming power in February 1933 not only reflected an industrial policy aimed at job creation, but also made mass motoring an integral element of the regime’s utopian social vision.